Monday March 9, 2015

The Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) releases two key documents each February related to salmon abundance: a Review of Ocean Salmon Fisheries, which evaluates the status of salmon fisheries on the West Coast for the previous year, as well as the Preseason Report, which forecasts their predictions for the upcoming year. In the latter, the preseason predictions of Sacramento River fall-run Chinook abundance are estimated using a model based on the relationship between the calculated Sacramento Index (SI) values (which is the sum of total of harvest – both ocean and in-river – and escapement for Sacramento River fall-run Chinook in a given year), and the number of jacks (two-year old salmon) that escaped to the Sacramento Basin rivers during the previous fall (see more explanation in our previous Fish Report). This abundance prediction allows the PFMC to determine management strategies and fishing regulations.

In the past, these calculations have consistently overestimated abundance, and a report written in 2013 by researchers from the National Marine Fisheries Service and University of California Santa Cruz acknowledged that all the forecasting methods they reviewed contain “substantial errors,” indicating it is difficult to accurately forecast Sacramento River Fall-run Chinook given the limited data available (Winship et al. 2013). The SI is a multigenerational index of abundance, but the preseason forecasts are calculated using only the escapement of jacks. Improvements in tagging and escapement programs over time should allow for age-specific abundance forecasts and increase confidence in preseason predictions.

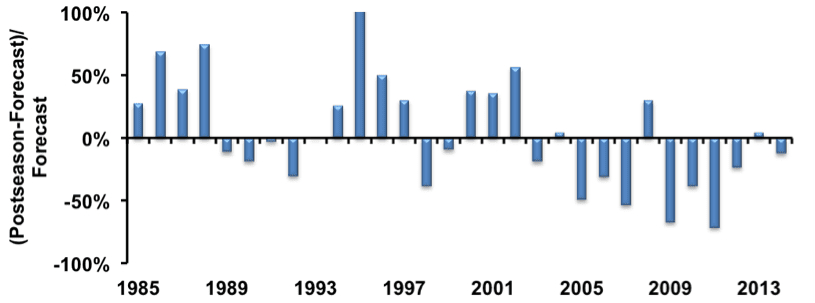

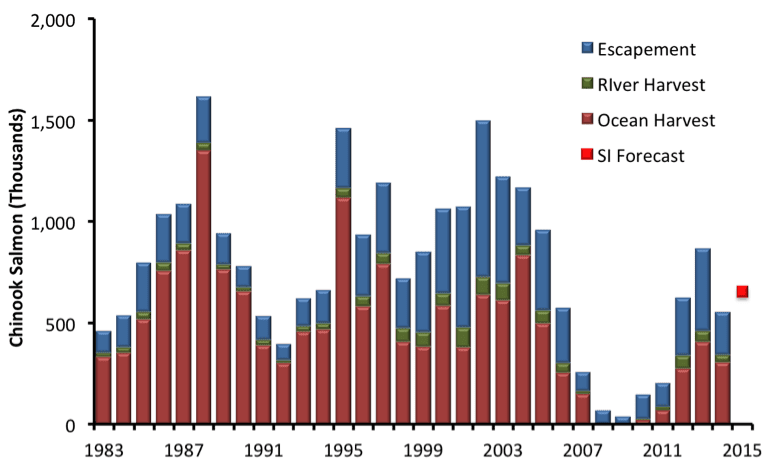

In 2014, PFMC modified the methods used to calculate preseason abundance estimates by switching from a linear model to a logarithmic regression curve. While the old method would have estimated 476,342 Chinook salmon for last year’s preseason forecast, the new method predicted 634,650 salmon for the forecast, and therefore no restrictions were imposed on the Chinook salmon fishery for 2014. At the end of the season, the final SI total reported by PFMC was 554,932 (right in between the two predictions), with 167,116 salmon returning to spawn in river and 44,552 in Central Valley hatcheries. The result was an exploitation rate of 62%, which is higher than in fourteen of the last sixteen years. While it is acknowledged that Chinook salmon forecasts for the Central Valley need improvement, PFMC has overestimated the SI by 13–72% in nine of the past 12 years (Figure 1). While the PFMC’s minimum escapement goal of 122,000 Chinook salmon was still met in 2014, the overestimation of the index is a continuing concern for management of Central Valley salmon harvest.

Using the new prediction model to forecast 2015, PFMC is anticipating that the SI will be 651,985 salmon, based on the 25,359 jacks that returned in 2014, which is just 3% higher than what was forecast for 2014 (Figure 2). Under their guidelines, expected harvest can account for up to 70% of the index, leaving at minimum 195,596 fish for escapement to hatcheries and rivers in the Central Valley.

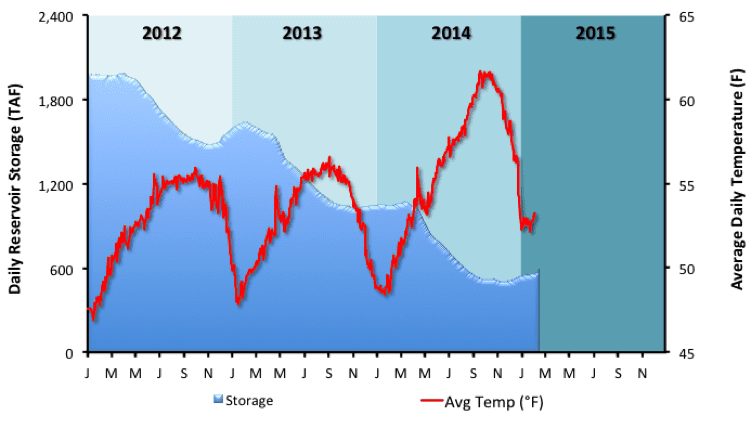

We are only just beginning to see returns of adult salmon that were impacted as juveniles by the drought in California, which is now in its fourth consecutive year. On some rivers, reservoirs have lessened the initial impacts of the drought because a reservoir can provide cold water to the rivers during warm periods. But as reservoirs continue to be drawn down during consecutive dry seasons, the cold-water pool is depleted and water temperatures can become lethal to fish (Figure 3). Many of the Chinook salmon that will return in the fall of 2015 were spawned during the beginning of the drought, but we may not see the most serious impacts until 2017 (Table 1). The drought is an unpredictable factor in Chinook salmon survival, and population forecasts may become even more difficult to predict in the near future. While salmon have survived long periods of drought in California’s past, it would be beneficial to err on the side of caution when predicting populations, especially when forecasts have been so inconsistent.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.