Monday April 18, 2016

Usually, “winter” makes people think of cold, blowing snow, and ice – but no winter-run Chinook salmon alive today experience conditions like that. In fact, the only existing winter-run Chinook salmon population in the world is located in hot, dry California. Chinook salmon, and all other Pacific salmon and trout in the genus Oncorhynchus, require cool, fast flowing water for survival, especially during their sensitive early life stages. These days, with severe drought and record high temperatures, it is hard to imagine how any Pacific salmon or trout populations became established in California, the southernmost and warmest limit of the distribution of Pacific salmon around the world. About half of salmon eggs laid are expected not to survive at temperatures greater than 60° F, and no eggs survive at temperatures greater than 62°F (Myrick and Cech 2001). While summer Sacramento River temperatures can exceed 70°F, these cool-water loving fish have been able to survive in California by mostly avoiding inhospitable warm river conditions – until the current drought changed things.

There are four races of Chinook salmon in California, and all are named for the timing of when the adults migrate from the ocean to the rivers to spawn. Fall-run and late-fall-run Chinook salmon adults migrate out of the ocean and up the rivers in the fall. By migrating and spawning in the fall, these fish avoid summertime in California rivers all together, and allow their offspring to grow from eggs to fry during cool and favorable river conditions in the winter, then migrate to sea during the following spring. Spring-run Chinook salmon adults migrate from the ocean to the rivers in the spring. The relatively hardy adult spring-run fish must hold in the rivers through the summer before they can spawn in the fall, allowing their more vulnerable offspring to rear during the winter and migrate to the ocean the following spring. As you have probably guessed, winter-run Chinook salmon adults migrate from the ocean into the rivers in the winter. Adults spawn through the spring and summer, which means their offspring must endure California’s often inhospitable summers through their sensitive early life stages. Historically, winter-run and spring-run Chinook salmon that spend their summers in California rivers were able to survive in relatively high-altitude creeks that are cooled by Sierra snowmelt and cold water springs during the summer, but this is no longer an option for winter-run Chinook salmon.

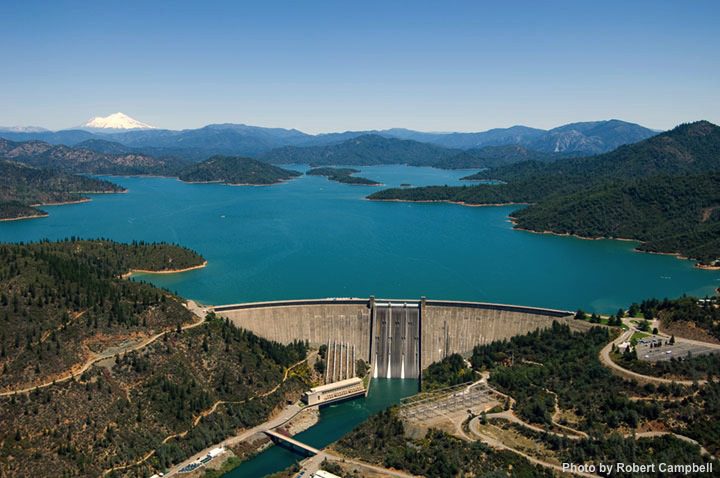

With the growing water demands of California’s expanding human population, dams were constructed on all major California rivers, blocking access to the high-altitude creeks used by salmon during the summer. These changes to California’s rivers has been particularly detrimental to winter-run Chinook salmon. Completion of Shasta Dam, located in the upper Sacramento River, in 1943 blocked access to nearly all creeks used by winter-run Chinook in the summer, and vulnerable winter-run eggs and hatchlings were forced to endure the often harsh summer river conditions downstream of Shasta Dam. The only reason winter-run Chinook salmon have been able to survive without access to their historical habitat is a large cool water pool that accumulates in the bottom of the huge reservoir created by Shasta Dam (Lake Shasta). The same cold snowmelt and spring water that provided continuously cool summer water temperatures in the historic winter-run creeks of Mount Lassen and Mount Shasta drains into Lake Shasta, and, because cool water is heavier than warm water, it sinks to the bottom of the lake. For a few decades, release of this vital cool water through Shasta Dam created a 44-mile haven below Keswick Dam (close to Redding), in which Chinook salmon eggs and hatchlings could grow and prepare for downstream migration.

Cool water releases from Lake Shasta kept winter-run Chinook salmon populations relatively high, with 118,000 adults returning to the upper Sacramento River in 1969 (Yoshiyama et al. 1998). However, with increasing human populations, it became more and more challenging to meet human water and power demands while maintaining the cool temperatures required by Chinook salmon in the upper Sacramento River. Winter-run Chinook numbers began to rapidly fall after 1969, and during the last extreme drought period in the 1990s, adult spawning numbers dropped to an alarming 200 salmon during two separate years (Yoshiyama et al. 1998). On the brink of extinction, winter-run Chinook salmon were designated as endangered under the California Endangered Species Act in 1989 and the Federal Endangered Species Act in 1994. Thanks to a hatchery supplementation program at Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery; strict management of downstream obstructions, like Redd Bluff Diversion Dam, to maximize upstream fish passage success; tight restrictions on ocean harvests of adult Chinook salmon; and construction of a Temperature Control Device on Shasta Dam, winter-run numbers had partly rebounded to nearly 20,000 adult spawners in 2007. As resource managers worked to balance water needs for consumption and the environment, the future was looking brighter for winter-run Chinook salmon. Then the recent extreme drought began in 2012, providing very little water to manage. In both 2014 and 2015, the Lake Shasta cool water supply was depleted long before the winter-run hatchlings had the opportunity to leave the upper Sacramento River, and it is estimated that only five percent of winter-run eggs survived in both years. We’ll discuss the current plight of winter-run in an upcoming Fish Report – stay tuned!

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.