Monday May 18, 2020

Weeds may be annoying to gardners, but they can prove devastating for ecosystems once they escape into the environment, leaving no space for native plants and animals. This is the case in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where non-natives represent half of the plant species and make up most of the aquatic plant cover. Despite control efforts, the problem has continued to grow. New and innovative solutions are needed to address this challenge, and a recent report from the Delta Stewardship Council provides recommendations on how to deal with the expensive and ecologically destructive issue (Conrad et al. 2020). With thousands of acres of planned restoration sites threatened by the spread of aquatic weeds, there’s no time to waste.

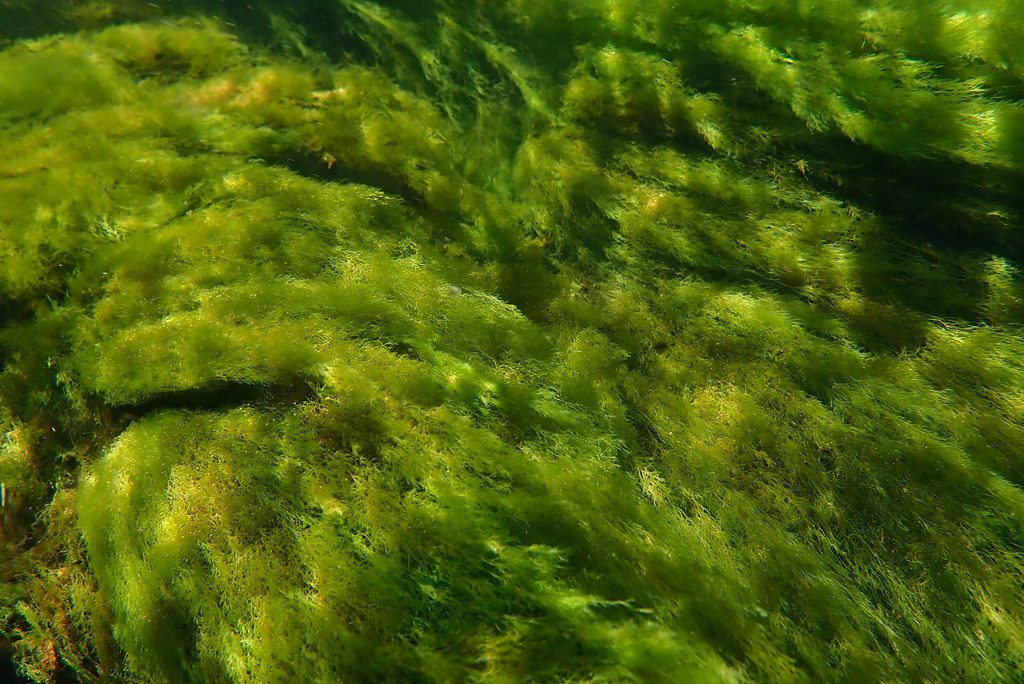

From 2004 to 2018, the area invaded by aquatic weeds in the Delta doubled, and weeds now cover about a third of all channels. Of the different types of weeds, submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) like Brazilian waterweed (Egeria densa) is the most difficult to control. Dense SAV is a major stressor on aquatic ecosystems and can lead to warmer water temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen levels, increased water clarity, and slower water velocity. Aquatic weeds may also change the food web by making it harder for beneficial algae to grow. All of these changes negatively impact native California fish species and favor invasive species like black basses and sunfish. Unfortunately, many restoration projects designed to create habitat and increase food production for delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus) and juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) are at risk of being invaded by aquatic weeds. In addition, aquatic weeds can negatively impact recreational boating and commercial shipping, water export, and fish salvage operations at the Federal and State Water Projects.

The only entity permitted to treat aquatic weeds in the Delta is the California Department of Parks and Recreation Division of Boating and Waterways (DBW) Aquatic Invasive Plant Control Program (AIPCP). Under the new Biological Opinions, this program is permitted to treat a total of 15,000 acres of floating aquatic vegetation and SAV in the Delta each year. However, staffing and funding limitations mean that meeting this target will be difficult, and the acreage authorization does not cover the full extent of aquatic weeds in the region. The Biological Opinions also authorize limited experimentation with new control methods, and since recent studies indicate that the current approaches are not providing effective SAV control, experimenting with new approaches is crucial. Restrictions on where new tools can be used are based on historical delta smelt distribution. Consequently, experimentation is generally not permitted in areas targeted for restoration, but these areas may be the most in need of innovative approaches for weed removal.

Control efforts are also stymied by the lack of a consistent monitoring program. DBW conducts boat-based hydroacoustic surveys to guide treatment site selection and to evaluate treatment effectiveness, but this labor-intensive process can only be conducted in about 5% of the Delta. Collaboration between DBW and NASA has allowed for the development of a satellite-based approach to track new infestations of floating vegetation, but this is not effective for SAV. Effective remote sensing of SAV relies on hyperspectral imagery taken from low-flying aircraft, paired with intensive ground-truthing. UC Davis has intermittently worked with several entities over the last 20 years to conduct these operations and to produce maps of the extent of SAV, but the lack of sustained funding means that maps are not created each year unless an interested agency pays for them.

The authors of this report call for prioritizing funding and authorization to test new approaches for aquatic weed control at Decker Island and Prospect Island, two Fish Restoration Program restoration sites. They suggest that determining the effectiveness of new control methods will require rigorous testing, and that a collaborative effort between the Fish Restoration Program and the AIPCP could rapidly evaluate effectiveness. They also advise that it is essential to secure funding for consistent Delta-wide monitoring of aquatic weeds, noting that addressing this problem is vital to the missions of all agencies in the Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee. As aquatic weeds rapidly expand and threaten tens of thousands of acres where substantial investments have already been made in tidal wetland restoration, any delays could prove very costly, both ecologically and economically.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.