Monday April 9, 2018

The year was 1991; California was entering a fifth year of drought, Sierra snowpack was at 18 percent of the historical average at the beginning of March, and water storage was critically low. By the end of the month, snowpack in the Tahoe region peaked at 75 percent of average and the ski resorts dubbed it a “Miracle March” that saved the ski season. While the series of storms that fell in March 1991 improved water conditions in the state, the drought persisted for yet another year.

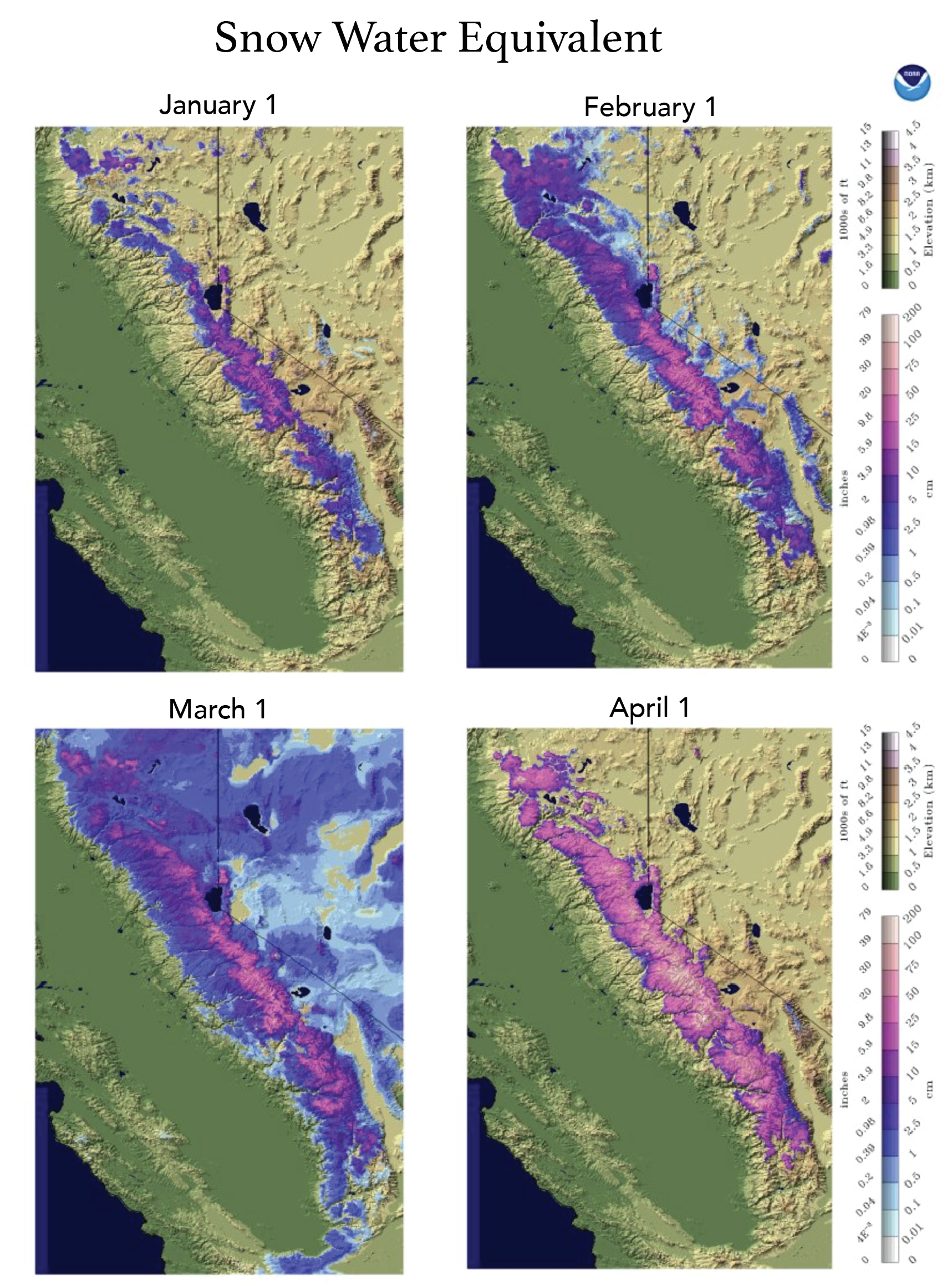

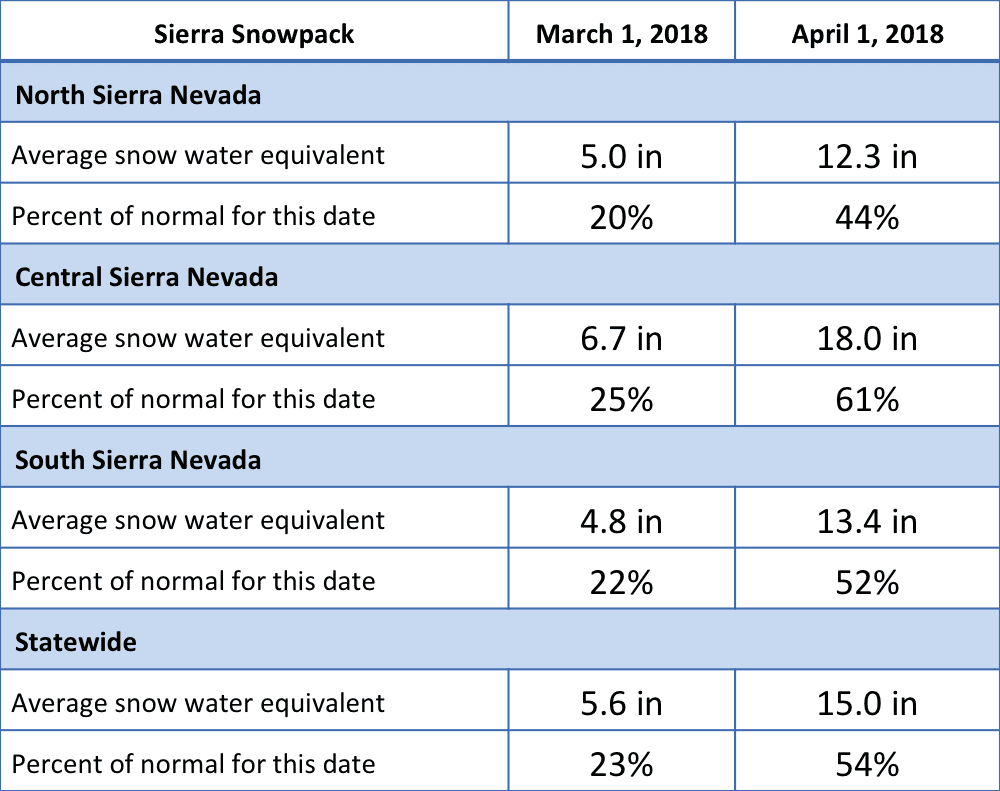

While this year has many similarities to 1991, it falls short of a “Miracle March.” Before a series of storms paraded into California, Sierra snowpack was at a bleak 23 percent of normal at the beginning of March (5.6 inches snow water equivalent, which is the depth of water that would cover the ground if the snow melted). By April 1, the benchmark date used to measure peak snowpack, Sierra snow water content reached 54 percent of average (15.0 inches snow water equivalent). While snow water equivalent for the state more than doubled in one month, it still remains just a little better than half of the historical average. Although the fresh snowfall in March made for superb skiing conditions, it still falls well short of an average water year. As the California Weather Blog puts it, this was more like “March Mitigation.”

Snowpack across the western United States appears to be dwindling. A recent study by researchers from Oregon State University and the University of California, Los Angeles found that 90 percent of snow monitoring stations have tracked declining levels of snow water equivalent measurements since 1955 (Mote et al. 2018). The study model also shows that snow water equivalent measurements have declined between 15 and 30 percent over the past century. The authors contend that the volume of water storage in the form of snowpack lost since 1915 is equivalent to the capacity of the West’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead (36 km3; 29 MAF) and continued climate warming will lead to snowpack continuing to decline at a similar or even faster rate.

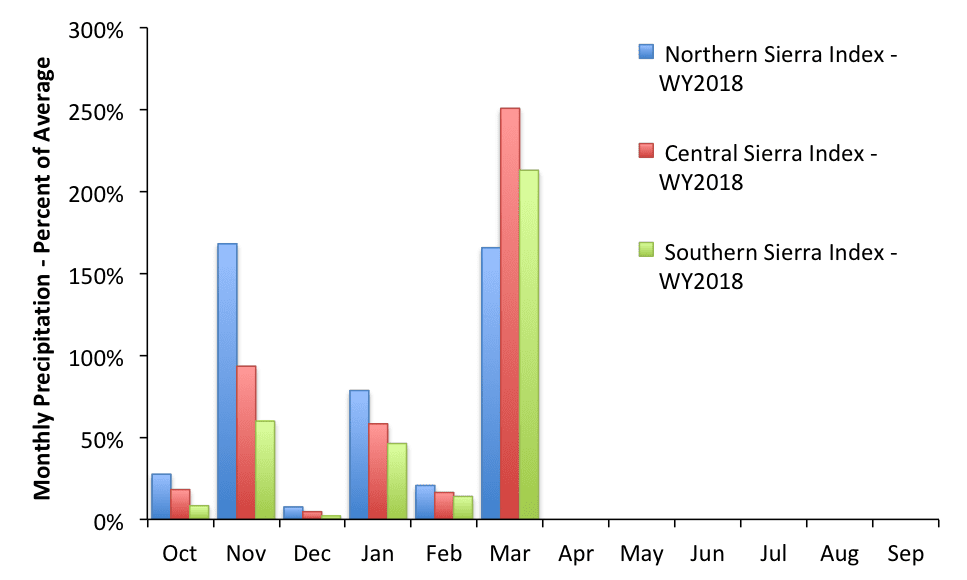

Snow is particularly important to California’s water supply because of its ability to store water and release it slowly over a couple of months. However, precipitation in the form of rainfall also contributes to our water supply as long as we have the capacity to capture it. At the end of the 2017 water year most of California’s reservoirs remained at above-average levels, and many had to conduct flood-control water releases to allow for elevated inflows during the recent series of storms from atmospheric rivers. This March was a banner month for rainfall, with precipitation at 165 percent of average for the North Sierra Index, 250 percent of average for the Central Sierra Index, and 213 percent of average for the Southern Sierra Index. However, because of the previous dry months, the season-to-date precipitation averages are not quite as good: 77 percent in the north, 76 percent in the central state, and 62 percent in the south.

Even 2018 can tout the fifth most productive March on record in terms of rainfall, it cannot erase the deficit created by the five previous dry months of this water year. With less than 20 percent of annual precipitation typically falling after April 1, it’s likely the 2018 water year will finish below normal. It is up to all of us to continue implementing water conservation strategies as we wait and wonder what next year will bring us.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.