Monday December 11, 2023

Geopolitical boundaries very rarely demarcate a fish’s natural distribution, but if there was ever a case when state lines seem to define a species’ range, it would have to be for the tidewater goby (Eucyclogobius newberryi). Tidewater goby are small, annual, cryptic fishes, rarely exceeding about two inches in length. They inhabit coastal lagoons from Crescent City, near the Oregon border, to San Diego, but have never been found in Oregon or Mexico. The number of tidewater goby populations greatly declined during the late 20th century, likely due to heavy coastal development, and the species was listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1994.

Tidewater goby habitats are typically separated from the Pacific Ocean by sandbars for most of the year, which effectively isolate populations and prevent fish from moving amongst existing populations or colonizing new habitats. When estuaries breach and spill into the ocean, typically during periods of high rainfall and large surf, they often drain rapidly. This is followed by an influx of ocean water as the breached lagoon is subjected to tidal influence, which can drastically change the salinity and temperature of the lagoon.

Several life history adaptations allow tidewater goby populations to persist in these environmentally challenging habitats. They have been found in water with salinities ranging from 0 (fresh water) to 42 parts per thousand (ppt). The upper end of this range is considered saltier than typical ocean water off the California coast, which usually has a salinity of around 35 ppt. Surprisingly, laboratory experiments have confirmed that tidewater gobies can tolerate salinities up to 54 ppt. However, juvenile gobies appear less resilient to breaching events, and can suffer high mortality rates when they are exposed to drastic increases in salinity. Temperatures within coastal lagoons, where tidewater gobies reside, typically range from 10 to 25 degrees Celsius (50 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit), but this wide temperature range is apparently not a limiting factor for their persistence. Furthermore, tidewater gobies do not seem to be limited by low dissolved oxygen levels and can persist and thrive in turbid wetlands, ditches, and marsh habitats where few other fishes can carve out a living. Three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) and introduced western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), which are often found in the same areas as tidewater goby, are notable exceptions.

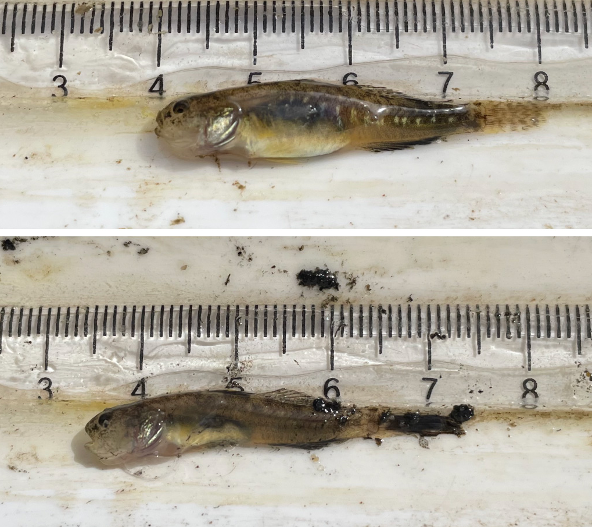

Unlike most fish species (which have a rather defined spawning period), tidewater goby can reproduce throughout the year, though increased spawning activity is generally observed from late spring through early fall. Individuals can become reproductively mature at lengths under 30 mm, and can actively spawn over prolonged time periods (several months). As a result, tidewater goby populations are typically characterized by a broad size and age structure through the continuous presence of both juveniles and adults, which allows these lagoon specialists to take advantage of favorable environmental conditions for reproduction, irrespective of season. This reproductive strategy is thought to balance the risk of high juvenile mortality by maximizing reproductive output. Some reproduction can occur during all times of the year (ensuring the continual presence of salinity-tolerant adults), while peak spawning activity is observed during summer when the chance of estuary breaching (and potentially high juvenile mortality) is lowest. Documentation of gravid (with eggs) and post-spawn females during a single survey is indicative of ongoing reproduction, as observed during a survey of the Salinas River Lagoon in May of 2023 (see images below).

Despite being resilient to environmental stressors, the species continues to struggle. Coastal development has drained, altered, or isolated goby habitats, making coastal wetlands either unsuitable or impossible to reach. Even under natural conditions, recolonization of suitable habitat after local disappearance events requires temporary connectivity between habitats – during breaching events, for example. However, the likelihood of a lagoon breaching, gobies entering and surviving the ocean environment, and finding their way into another suitable lagoon that happens to be breached at the same time intuitively seems low, and is indeed rare, particularly in the northern part of the species’ range.

While downlisting of tidewater goby from “Endangered” to “Threatened” has been proposed (but not yet occurred), there are some examples providing hope that the species may be on the road to recovery. One such example is the Salinas River Lagoon, where tidewater goby had been absent since the early 1950s, presumably disappeared due to the discharge of poorly treated sewage into the lagoon (as cited in the recovery plan for the species), in combination with extensive levee construction and channelization. Following over 60 years without documentation of the species in the lagoon, tidewater goby were observed during a survey in 2013, and again in 2014, when tidewater goby were the second most abundant species sampled in the lagoon! Periodic surveys since that time have continued to document tidewater goby, sometimes in high abundance! FISHBIO continues to annually monitor the Salinas River Lagoon to provide timely information on the distribution and abundance of tidewater goby, ensuring that lagoon management provides favorable conditions for the persistence of this charismatic and endemic California fish species.

This post is part of our Species Spotlight Series to commemorate the ESA’s 50th anniversary. Follow these posts to learn about threatened and endangered freshwater fish and the role the ESA plays in their continued conservation!

Header Image: A tidewater goby in a viewing box.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.