Wednesday May 19, 2021

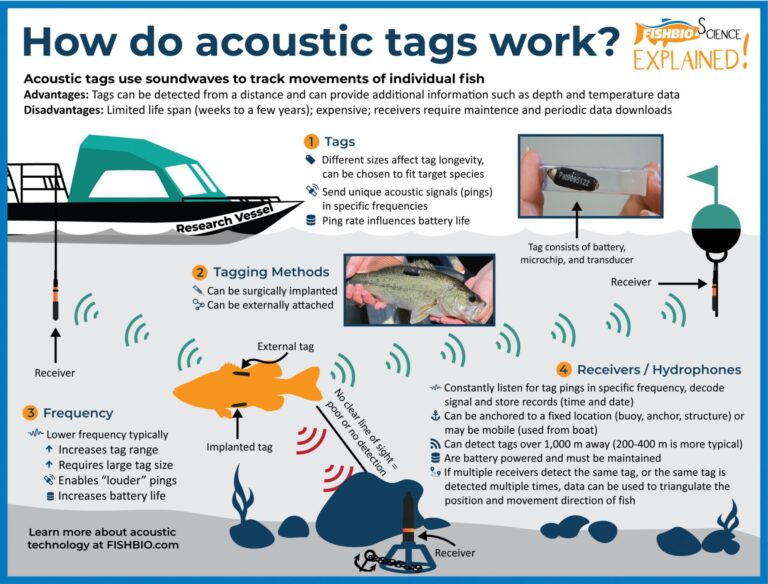

Two of the biggest challenges in fisheries research are that fish are hard to see underwater, and they are always on the move. Fortunately, acoustic telemetry offers a way for scientists to overcome some of these sizeable challenges using the technology of sound. First applied in the 1950s, acoustic telemetry uses two essential pieces of equipment: tags (which are like beacons) and receivers (or listening devices, often referred to as hydrophones). The basic concept, depicted in our infographic above, is rather simple: the tag (also called a transmitter) is implanted or attached to a fish, the fish is released, and the sound signal given off by the tag is detected by a hydrophone.

Hydrophones can be stationary or mobile: stationary receivers can be mounted or anchored at a location that a fish is expected to move past, such as a bridge pillar, while mobile receivers are deployed from a moving boat, allowing researchers to cover a wider area in an attempt to seek out the location of the tagged fish. Each tag emits a unique signal, which makes it possible to identify individual fish (or individuals belonging to a group). When detected, the receiver records the unique identification number of the tag, along with a date and time stamp, so that a network of receivers (often called an array) can be used to reconstruct movement pathways and migration speed. The intention and design of the study influence the level of detail that can be obtained – relatively few hydrophones spread over a large distance can provide useful information on migration characteristics, while multiple receivers clustered in a small area can reveal minute details of a tagged fish’s behavior through triangulation, helping to determine a fish’s exact location in a body of water.

Among the main advantages of acoustic telemetry is that fish can be detected without the need to recapture the individual. Tags can also incorporate additional sensors and transmit parameters such as depth and temperature. However, there are also numerous challenges that must receive careful consideration in study planning. Perhaps chief among these, tags and receivers are expensive, although the cost of sophisticated telemetry equipment has decreased significantly in recent years. In addition, tags have a limited life expectancy, as the batteries that power them eventually run out – battery life is much shorter (days to weeks) in smaller tags that send signals in short intervals, and longer (months to years) in larger tags that hold larger batteries. A related limitation is fish size: small fish require very small tags, which can only function for short time periods. Finally, correct interpretation of data can be very challenging – for example, a tag may continue to transmit after the fish carrying it dies or gets eaten – in which case the movement of the predator may be confused with that of the target organism. Despite these challenges, researchers continue to refine hydroacoustic methods, and have used them to gather a wealth of important information about the otherwise invisible, highly mobile lives of fishes.