Monday March 10, 2025

The revelation that 25% of freshwater fish species are threatened with extinction has drawn more attention to the plight of underwater diversity, which was historically “out of sight, out of mind.” But a deeper diversity crisis remains largely hidden, namely the loss of diversity within species. This “intraspecific” diversity is critical for species persistence in an increasingly unpredictable world but is challenging to investigate. Fortunately, improvements in analytical methods allow scientists to better understand this within-species diversity, as demonstrated in a recent study of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in the Yuba River in California (Willmes et al. 2024). Researchers conducting this study integrated data obtained from different techniques to reconstruct and monitor changes in diversity within this population of Chinook, and their findings have important implications for future conservation plans.

Intraspecific biodiversity can be interpreted in two main components. First is genetic diversity, or variation in the genetics of individuals within a population. Second is phenotypic diversity, which refers to the physical characteristics of an organism created by the interaction between its genes and its environment, including migratory patterns in salmon. These aspects of diversity buffer populations in the face of changing environmental conditions. Salmon, in particular, exhibit a high level of intraspecific diversity, as evidenced by the four distinct runs of Chinook salmon in California. This diversity helped maintain population stability in the face of changing conditions over millennia but, with the advent of dams and other human development, the effectiveness has started to wane. Thus, understanding genetic and phenotypic diversity in salmon is a key part of developing effective conservation strategies.

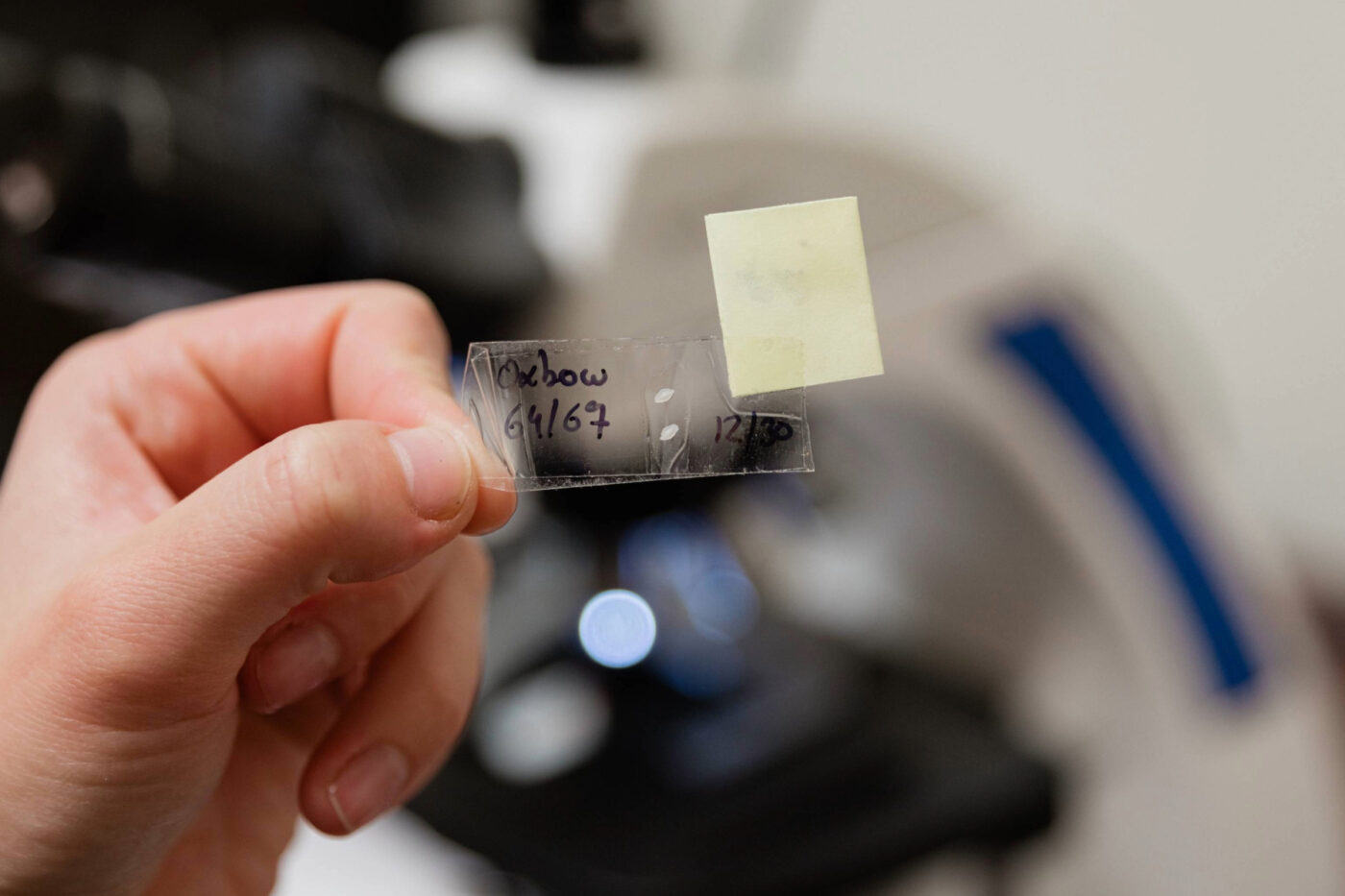

Two runs of Chinook salmon – spring-run and fall-run – are present in the Yuba River. These two runs are differentiated by the time of year adults return to their natal rivers (spring and fall, respectively). Spring-run are particularly impacted by dams which block access to snowmelt-fed tributaries where they historically oversummered. For rivers like the Yuba, where multiple runs persist, understanding how hatchery practices and streamflow management impact the genetic integrity of each run is critical, and this is only possible through run-specific monitoring. Genetic techniques, like genotyping, have made this possible, but there is also a need to understand the diversity in origin, size, age-at-outmigration, and migration timing of each run. Analysis of the rings in otoliths (ear bones) of returning salmon, similar to tree rings, provides a ledger of a fish’s age and growth patterns. Plus, variation in where the fish is (e.g. fresh or saltwater habitat) and what it’s feeding on throughout its life creates subtle differences in the microchemical composition of each layer of the otolith, allowing scientists to reconstruct the movements a fish made throughout its life.

The origin of salmon returning to the Yuba to spawn is tricky to unravel because hatchery fish from other rivers may stray into the Yuba. But, by taking genetic and otolith samples from over 400 fish collected from 2009 to 2011 and 2018 to 2020, researchers determined where each fish originated using otolith microchemistry and the run each belonged to using genetic markers. Even further, otoliths were used to estimate fish age, size at emigration, and daily growth rates.

The results of their analysis showed that Yuba-origin salmon (meaning wild, non-hatchery fish) represented up to 73% of spawning adults in the river across the six years included in the study. Genetic analysis also showed that Yuba-origin fish included both fall- and spring-run individuals, and the proportions of these runs varied from year to year. Their reconstruction of sizes at emigration also showed variable patterns in juvenile outmigration strategies across years with different flow conditions, where juveniles tended to emigrate at later life stages in years with high flows. Additionally, their analysis of growth rates revealed that juveniles that moved downstream at a younger age and reared outside of their natal streams generally had faster growth.

By combining data from two different sources, this study provides unique insights into the Chinook population in the Yuba that could not be gleaned from genetics or otolith analysis alone. With the methods available today, researchers can specifically monitor intraspecific diversity. This will allow scientists to evaluate whether conservation actions are effective at maintaining intraspecific diversity and setting specific diversity targets in addition to the conventional abundance targets used to evaluate threatened populations. By uncovering intraspecific diversity, managers and researchers can more effectively promote ecosystem stability in a continually changing world.

Header Image Caption: Collected otoliths ready to be analyzed

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.