Monday May 10, 2021

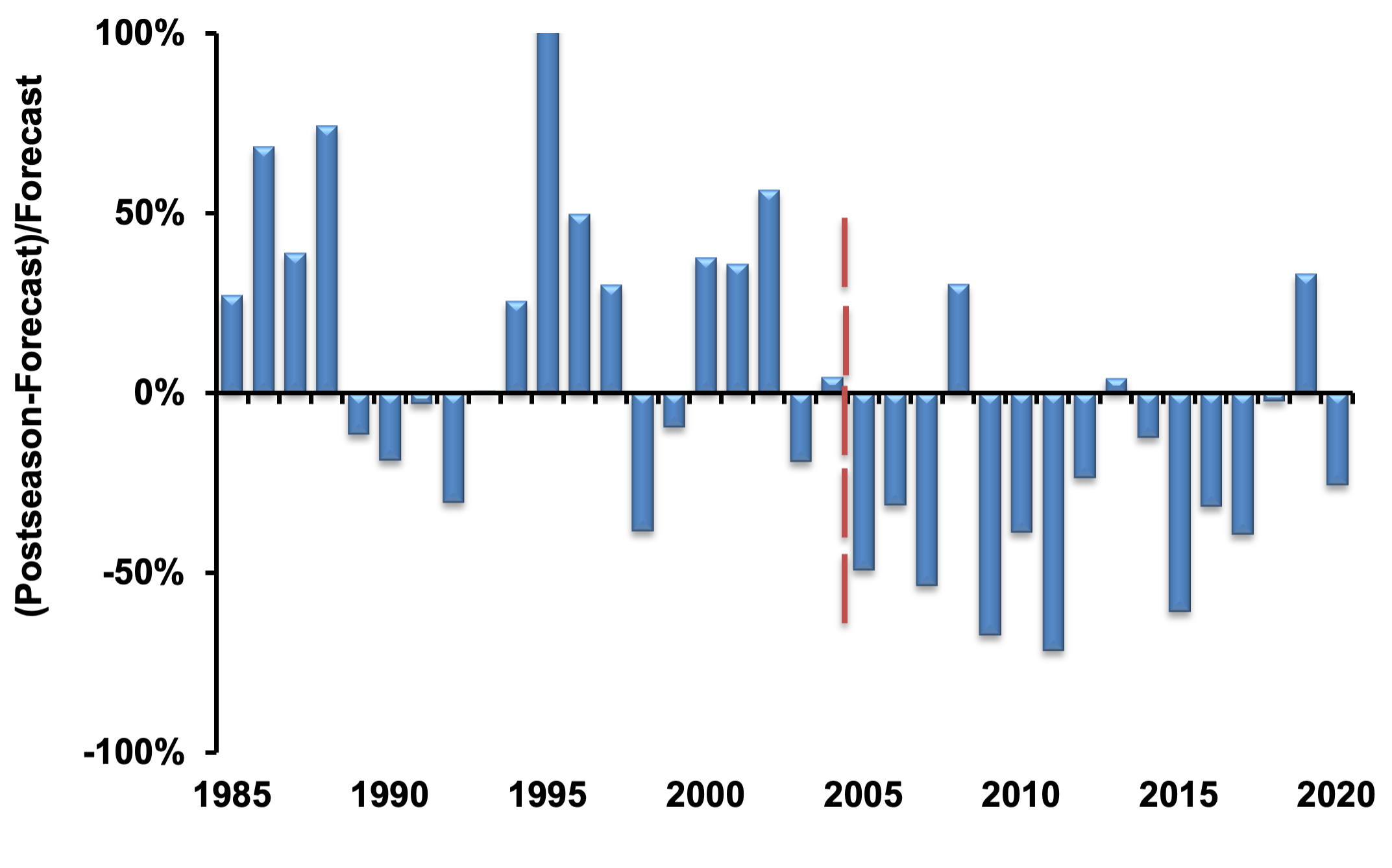

It’s time for our annual summary of the Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) Review of Ocean Salmon Fisheries. After surprisingly high returns in 2019, the California Chinook salmon population in 2020 failed to meet expectations (although was still larger than the depressed population levels seen following the recent drought). Each year, the PFMC publishes a report on the previous year’s salmon fisheries along the West Coast. The report details harvest totals and socioeconomic benefits for the California ocean fishery, as well as escapement totals, or the number of salmon that “escaped” the fishery and returned to the Central Valley. The report also provides an opportunity to compare these numbers with the preseason prediction that was used to set harvest regulations for that year. Inaccurate preseason predictions can have severe consequences: an underestimation can impose unnecessary restrictions on the commercial fishery, and an overestimation can lead to reduced escapement and low numbers of fish available for in-river recreational fishing. In 13 of the last 16 years, PFMC predictions have overestimated the size of the population (Figure 1), which in some years has led to higher than expected harvest rates and fewer fish returning to Central Valley streams. In 2020, the population was overestimated once again, and the actual population was 26% smaller than what was forecasted.

Figure 1. Percent difference from PFMC average annual preseason forecast relative to the actual SI observed, 1985-2020. Positive bars represent underestimates and negative bars represent overestimates. Source: PFMC 2021a

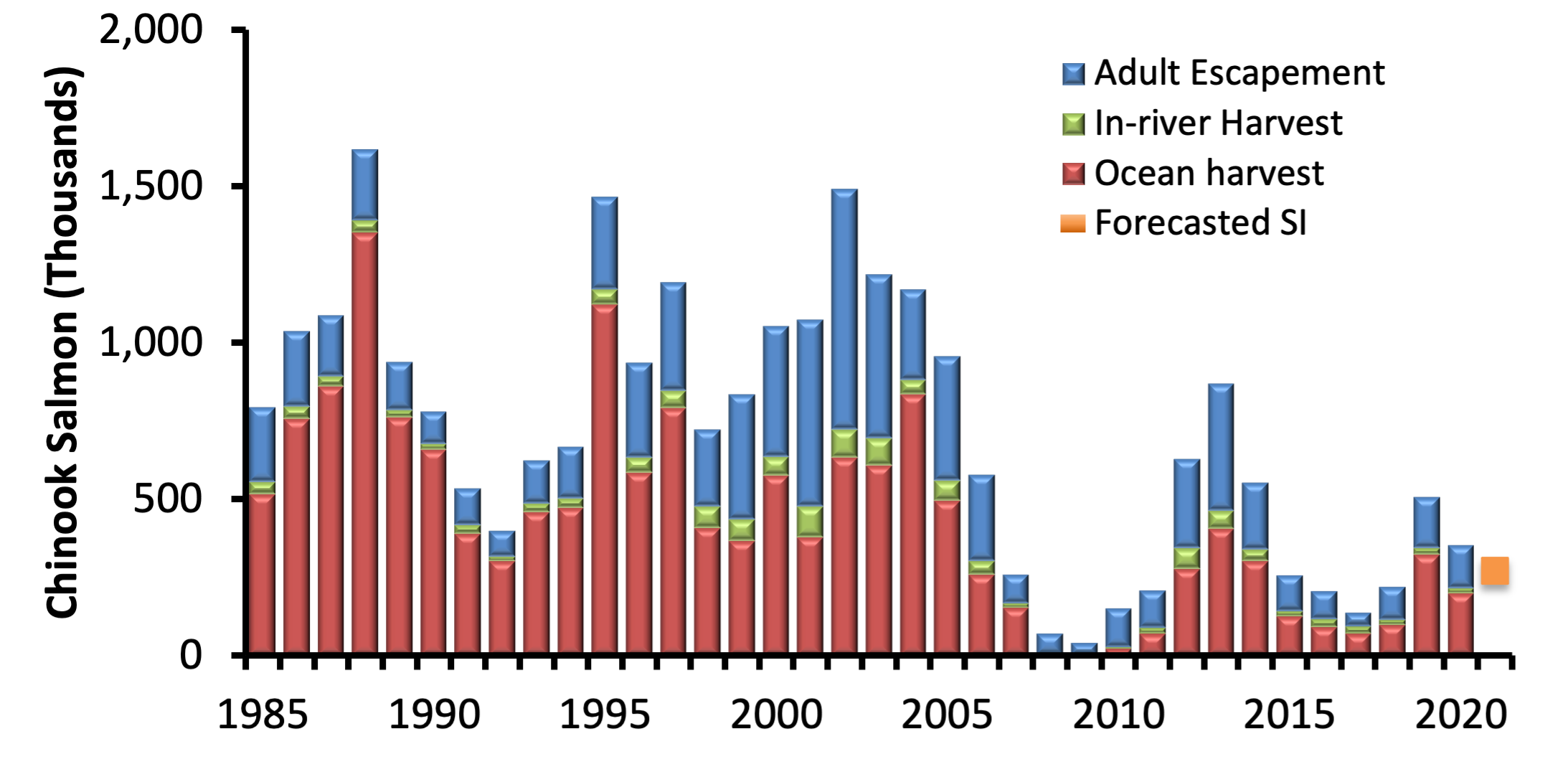

Results of the 2020 fishing season in California reveal a return to the reduced population levels of the last 5 years after a remarkable jump in both harvest and escapement totals for the Central Valley in 2019. The 2019 population likely reflected better conditions resulting from two historically wet years in 2017 and 2019, while the 2020 population is likely the result of recent dry conditions in the Central Valley. In California, the PFMC report focuses primarily on fall-run Chinook salmon in the Sacramento River Basin, as this population contributes the majority of fish caught in the ocean fishery. The metric used to represent this abundance is the Sacramento Index (SI), which is the total number of adult fish (ages 3–5) projected to be available in the ocean that will either be harvested or will escape to spawn in natural areas and hatcheries in the Central Valley. The preseason forecast for 2020 was an expected SI of 473,183 fish, with a total projected spawning escapement (to both hatcheries and natural areas) of 233,174 fish, based on fishing regulations and quotas. These were both among the highest forecasts in recent years.

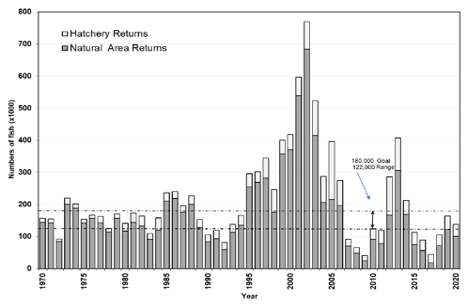

PFMC reported that the 2020 salmon season fell short of expectations with an actual SI of 351,925 fish. This is a 30% decline from the 2019 population, but is still higher than then the previous five-year average of 264,500 fish. In 2020, an estimated 137,907 fall-run Chinook salmon “escaped” the harvest and spawned in hatcheries and natural areas of the Sacramento River Basin, which is above the long-term management goal of 122,000 hatchery and natural area spawners, but 41% lower than the preseason forecast (Figure 2). Based on average escapement from 2018–2020 (133,549), the previously “overfished” stock is now considered rebuilt because it exceeds the PFMC escapement goal of 122,000 hatchery and natural area adults. Natural area spawners (100,064) outnumbered hatchery returns (37,843), which is common in most years, but is sometimes reversed in low-escapement years such as 2017 (Figure 3). However, it is likely that straying hatchery-origin fish also comprise a large percentage of the natural-area spawners.

Figure 2. Sacramento River Fall-run Chinook salmon ocean harvest, river harvest, and escapement, 1985-2020. Source: PFMC 2021a; 2021b

The salmon returning in 2020 were likely influenced by relatively poor outmigration conditions in 2018, when the majority of returning fish outmigrated to the ocean. This was especially true in the San Joaquin Basin, where cumulative survival from the upper San Joaquin River to the Golden Gate Bridge was only 0.5 percent (Hause 2020, San Joaquin River Restoration Program science meeting). This poor survival likely contributed to the alarmingly low number of adult returns to the San Joaquin River Basin, which experienced the lowest escapement total since the fishery collapse of 2009. In 2020, only 1,853 fall-run Chinook salmon returned to natural areas of the San Joaquin Basin and 3,628 salmon returned to Mokelumne and Merced River hatcheries, representing just 3% of the total fall-run escapement to the Central Valley. The total San Joaquin Basin escapement of 5,481 fish declined by 71% from the previous year (27,212), which was the second highest recorded escapement since 2002, and contributed 12% to the total fall-run escapement in the Central Valley. Although the San Joaquin Basin has historically constituted less than 10% of the total Central Valley escapement, its contribution has exceeded 10% every year since 2014, with an average contribution of 15%. It is not clear why the proportion of escapement has been relatively high in the San Joaquin Basin over the past few years, but it may be in part influenced by an increase in off-site hatchery releases during the drought.

Figure 3. Sacramento River adult fall-run Chinook escapement 1970-2020. Source: PFMC 2021a.

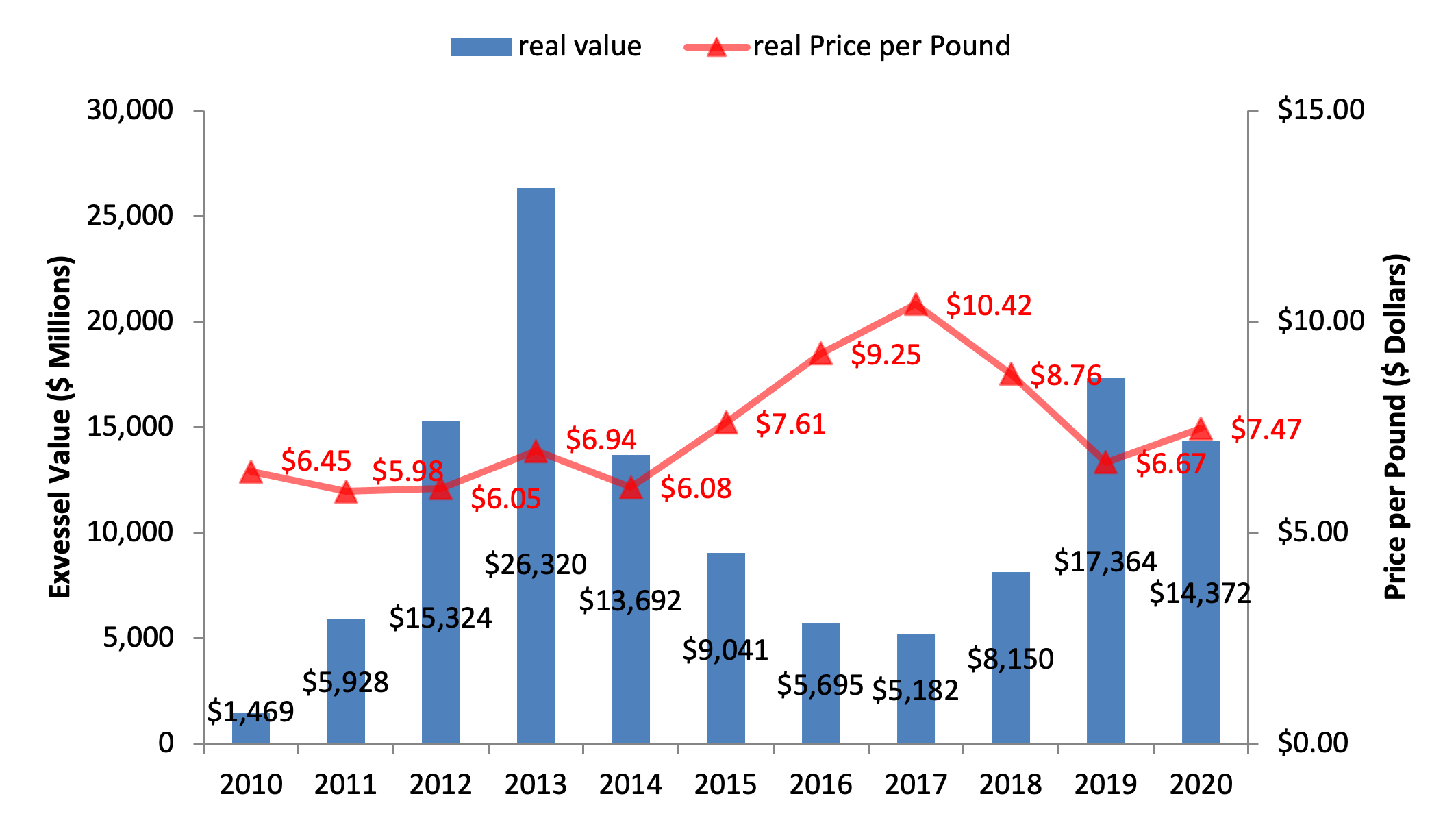

The commercial fishery harvest in 2020 declined from the previous year, but represented an improvement from the historically low numbers seen from 2015–2018. Landings revenues (coastwide exvessel value, or price received at the dock) totaled $14.4 million, which was a decline of nearly 20% from the prior year’s value of $17.4 million, but nearly 60% higher than the previous five-year average of $9.1 million (Figure 4). However, the California fishery continues to pale in comparison to historical landings, with 2020 revenues still 60% below the 1979-1990 inflation-adjusted average of $36 million (which include coho landings during that period).

The total commercial harvest of 177,334 fish in 2020 dropped by nearly 35% from the previous year (271,697), but was still the second highest total since 2013 and represented a 59% increase over the previous five-year average of 111,626. Commercial fishing effort (boat days fished; 12,268) was also reduced from the prior year’s total (15,774 days) but still higher than the 2016–2018 average of 7,167 days. The number of commercial vessels that made salmon landings in California declined to 472 in 2020, which was 98 fewer than those that participated the previous year. The average California exvessel price (i.e., price received at the dock) for troll-caught Chinook salmon increased from the prior year to an average of $7.47 per pound, which is still the second lowest price since 2015 (adjusted for inflation; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Commercial exvessel value and price per pound 2010-2020. Source: PFMC 2021a.

Unfortunately, anglers received unwelcome news from PFMC this year, with reduced forecasts leading to some of the more severe fishery restrictions seen in some time. If preseason forecasts are correct, there will be 270,958 Sacramento River fall-run Chinook in the ocean this year, which is 43% lower than last year’s projection, and 16% lower than the previous five-year average of 322,505. Given these discouraging preseason predictions, PFMC has decided to significantly reduce the ocean fishery this year to a total of only 78 days in the San Francisco management area and 45 days in the Fort Bragg management area, as opposed to last year’s 167 days. If preseason predictions are correct, California could be facing another dismal year for salmon abundance this summer and fall.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.