Monday October 21, 2019

When plumes of dust rise over almond and walnut orchards from the harvest and truckloads of fresh chopped corn make their way along the country roads to the dairies, you know it’s fall in the California Central Valley. It’s also the time of year when water managers make an assessment of the closing water year and look forward to the year to come. The water year runs from October 1 to September 30, and the 2019 water year that just ended was a good one by all measures. Rainfall, snowpack, and carryover storage were all higher than the previous year, and well above average.

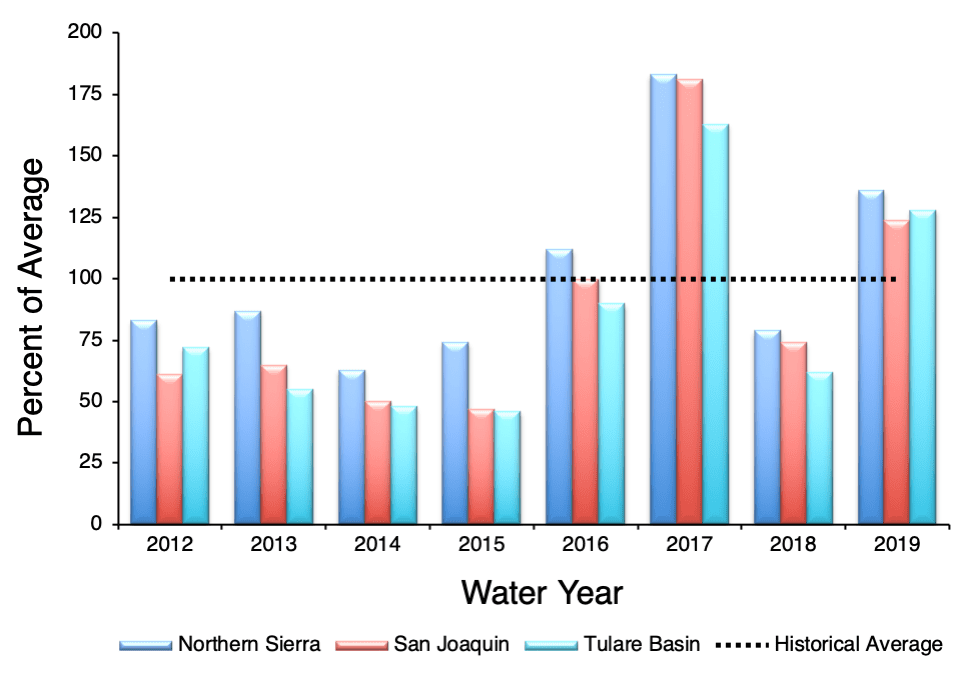

Caption: Average water indices for Northern Sierra, San Joaquin, and Tulare Basin 2012–2019.

The California Department of Water Resources reported that more than 30 atmospheric rivers made landfall to drench the state in the 2019 water year, many in northern California. The Northern California 8-Station Precipitation Index, which spans from Mount Shasta City south to Pacific House, registered 70.7 inches of rain, which is 136 percent of the 50-year historical average of 51.1 inches. The San Joaquin 5-Station Precipitation Index, which covers the Central Sierra Nevada mountain range from the Calaveras Big Trees south to Huntington Lake, recorded 50 inches of rain, which is 124 percent of average (40.2 inches). To the south of the Kings River, the Tulare Basin 6-Station Precipitation Index, logged 36.8 inches of rain, which is 128 percent of average (28.8 inches). All three regions were significantly higher than the previous year, which saw measurements of 79, 74, and 62 percent of average, respectively.

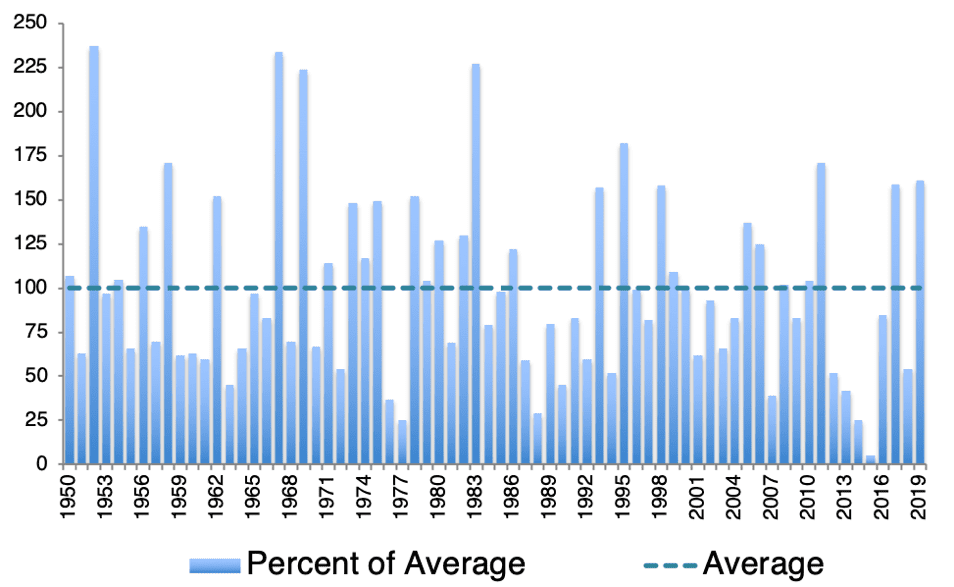

Caption: Statewide percent of average April 1 snow water content, 1950–2019.

The average measurement of snowpack water content generally peaks on April 1, so it is used as a benchmark for water management and to compare between years. On April 1, 2019, the statewide average snow water equivalent was 45.3 inches, or 161 percent of average. In recent years, the snowpack has melted away by the beginning of June. However, the snowpack persisted this year due to mild spring temperatures, and on June 1, 2019, remained at a whopping 202 percent of average for that date (16.9 inches). The slow melting snow this year allowed the reservoirs to capture and store a lot more water than would have been possible if it had melted more rapidly. When the spring runoff peaks earlier in the spring, reservoirs have to evacuate more water to make room for the runoff.

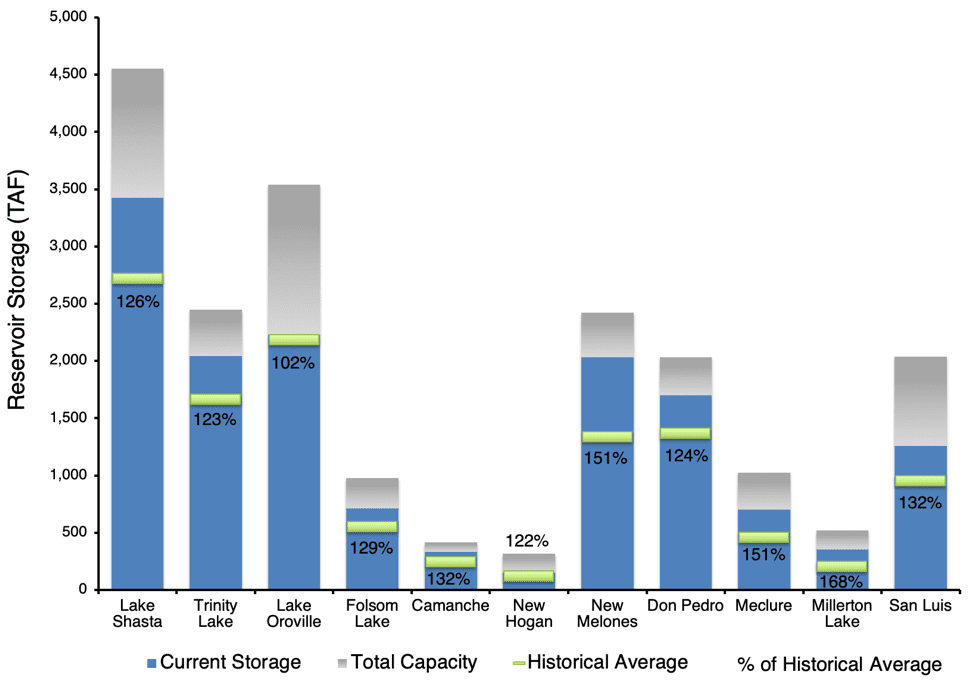

Caption: California reservoir storage and capacity as of October 1, 2019.

As a result of the above-average precipitation and snowpack, most of the major reservoirs in Northern California have been able to carry more water over into the new water year. When it comes to predicting weather conditions for the coming winter, it remains a coin toss. According to the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center, the El Niño/La Niña (ENSO) is expected to remain neutral through the fall and possibly into spring. The NOAA three-month precipitation probability model gives northwestern California a low chance (33% probability) of being drier than normal, and the rest of the state an equal chance at being above normal or below normal. Whether or not California enters into another dry period, our well-filled reservoirs suggest we are in good shape for the immediate future.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.