Monday June 3, 2024

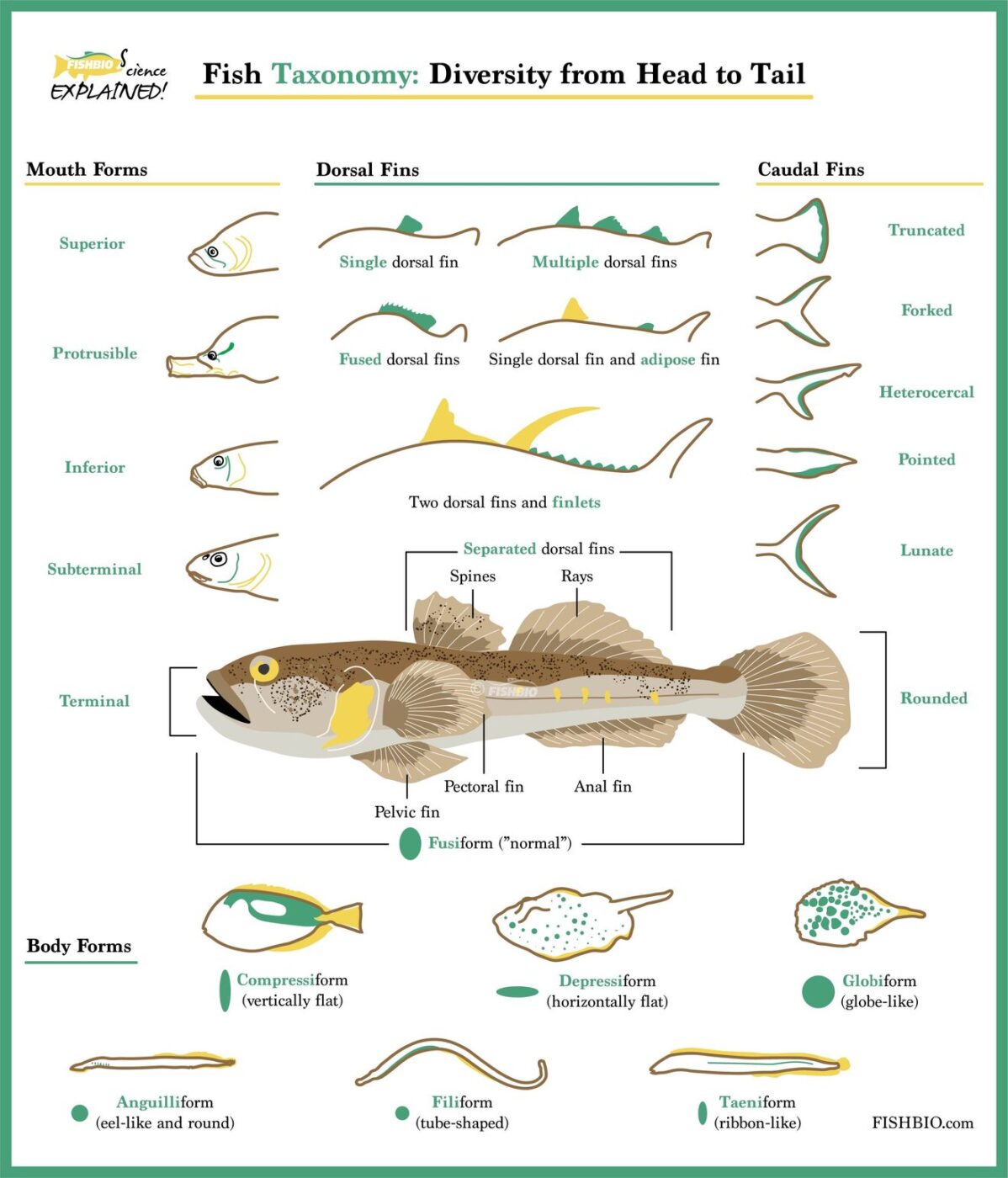

An important skill all fish biologists should possess is the ability to identify a fish in the field – but how can they distinguish over 30,000 species of fish from one another? Some fish species are easily identified at first glance, such as the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), whose bright and unique colors set it apart from any other fish. However, if the fish does not possess an extremely unique trait, then biologists need to look more closely at other attributes such as body and mouth forms, color, and tail and fin characteristics. The most obvious features – such as body form – are assessed to determine the fish’s family, and then genus and species within that family may be distinguished by finite details.

Major differences in body shapes are the simplest way to distinguish fish among families and begin species identification. For example, if a fish has an “anguilliform” (eel-like) body shape, then biologists can focus on species that belong to families with long, slender bodies, such as Anguillidae (freshwater eels). If a fish has a “compressiform” (flat) body shape, then scientists can focus on families like Pleuronectidae (halibuts and flounders). Additionally, the color of a fish can sometimes be used to determine its species. For instance, the cardinal tetra (Paracheirondon axelrodi) has extreme red and blue coloration, making it distinguishable from other similarly shaped species. Another example is the Mandarinfish (Synchiropus splendidus), whose vibrant blues and oranges are unlike any other fish. Once information is gleaned from the obvious features of body form and color, biologists can move on to a new characteristic to continue working towards species identification.

FISHBIO Science Explained graphic about various morphological characteristics used in fish identification.

Another way to differentiate fish families is by their mouth forms. Mouth forms come in a diversity of shapes and sizes, such as terminal, inferior, and elongated. The shape and angle of the mouth provide information on the ecology of the fish, such as what they eat, where they reside in the water column, and how they interact with the environment. If the mouth of a fish is superior (or pointed upwards) like mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), which feed on floating insect larvae and other invertebrates, then the fish likely specializes in surface feeding. Conversely, fish with subterminal or inferior mouths (mouths oriented downwards) tend to forage on the substrate or bottom of a river, lake, or ocean.

The Sacramento sucker has an inferior (downward pointing) mouth to help it consume food off the river bottom.

Dorsal, tail, and pectoral fins are also characteristics that can help identify a species of fish. The hard spines and soft rays in fins can be counted (a method known as meristics) or measured (morphometrics) to distinguish species from one another. For example, black bass (genus Micropterus) are known to have between 9 and 11 dorsal spines, followed by 11 to 14 soft dorsal rays, and counting the numbers of these different structures can help distinguish fish among Micropterus species. Other meristic traits that may be useful for species identification include counts of scales along certain parts of the body (such as the lateral line). Additionally, diagnostic morphometric traits used in species identification may include things like the ratio of body depth to body length and the percentage of eye diameter to head length.

Salmon have slightly forked tails.

Tail fins come in many shapes and proportions, including rounded, forked, and square, among others. Gobies (family Gobiidae), for example, are known to have rounded tails. This round tail shape combined with separated dorsal fins and a fused, suction cup-like pelvic fin, make it easy to determine that a fish is a goby. The lobes of tails can also help with species identification, as some species have a larger upper lobe compared to a smaller lower lobe (referred to as heterocercal), or vice versa (hypocercal). Lastly, the pectoral fins, or the anterior fins on the sides of the body, may have differences in length that can be measured to distinguish closely related species from one another.

Yellowfin goby (Acanthogobius flavimanus) have a pelvic disc to help them stick to or navigate substrate.

Some species of fish are so similar looking that external features alone aren’t enough to identify them. Certain traits require dissection to assess species differences, such as gut structure or teeth anatomy. As with external features, these internal characteristics often vary in fish based on their environment and what they eat. For instance, sucker fish (family Catostomidae) have pharyngeal teeth to help them grind and crush mollusks and invertebrates that they eat off the river bottom, while other fish like sturgeon (family Acipenseridae) lack teeth entirely. To make things more complicated, some fish species can hybridize with one another, and their offspring may have characteristics from both parents, which can make visual identification nearly impossible. These hybrids may only be readily identified by analysis of their DNA. Similarly, some “cryptic” species look virtually identical to one another and may only be distinguishable by molecular analysis. Sometimes examining DNA can reveal species hiding in plain sight, as was the case with the California Roach (Hesperoleucus symmetricus), which genetic analysis revealed to be five different species of roaches rather than just one.

By looking at and comparing the different features of a fish, biologists can often identify the exact species of fish captured while out in the field. However, if identification methods involving external features are not enough, molecular and dissection analyses back in the lab can help deduce the species. Familiarity with fish species likely to be present in a sampling area greatly helps scientists more easily identify what they catch just based on experience. However, with so many similar-looking fish out there, even the most seasoned fish biologists refer to a field guide now and again.

Header Image Caption: Samples collected by FISHBIO staff from the Nam Kading River during an aquatic resources project.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.