Monday July 4, 2016

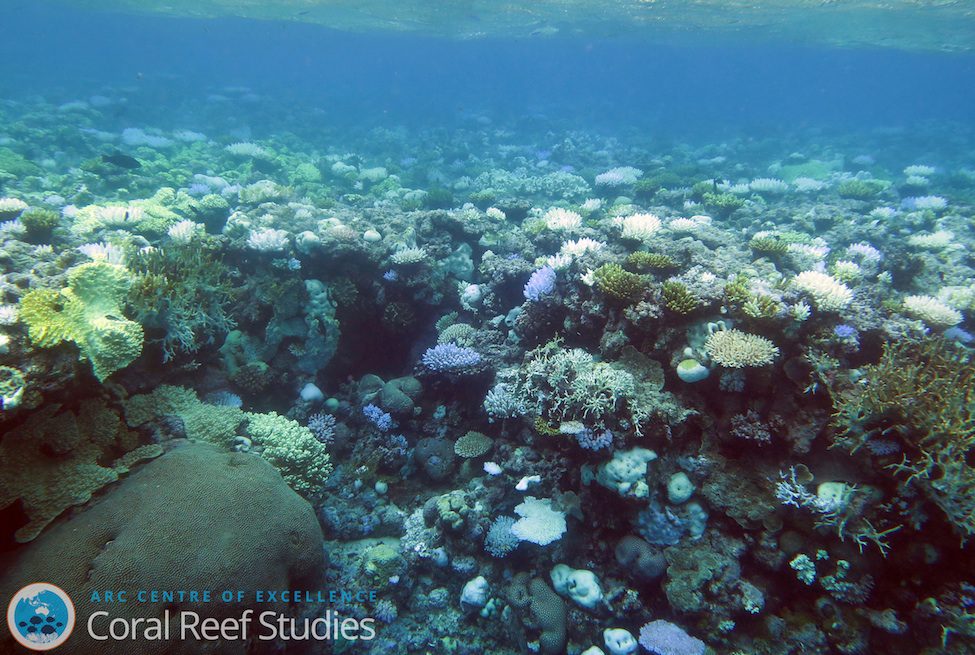

Coral reefs, which are sometimes called the rainforests of the oceans, are typically hotspots of biodiversity teeming with life. But El Niño and global warming are turning some of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef into ghost towns. Patches of once-colorful corals on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef are now stark, snowy white after a massive event called coral bleaching caused by warming ocean waters. El Niño-related weather events brought reservoir-filling rains to parts of California, and inflicted drought on Southeast Asia, but perhaps the most profound effect on the ocean is the unprecedented bleaching of corals in the Pacific Ocean, including the Great Barrier Reef. Scientists from the Australian National Coral Bleaching Taskforce report that bleaching damage has affected 93 percent of this iconic ecosystem and tourist attraction.

Coral reefs, which are sometimes called the rainforests of the oceans, are typically hotspots of biodiversity teeming with life. But El Niño and global warming are turning some of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef into ghost towns. Patches of once-colorful corals on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef are now stark, snowy white after a massive event called coral bleaching caused by warming ocean waters. El Niño-related weather events brought reservoir-filling rains to parts of California, and inflicted drought on Southeast Asia, but perhaps the most profound effect on the ocean is the unprecedented bleaching of corals in the Pacific Ocean, including the Great Barrier Reef. Scientists from the Australian National Coral Bleaching Taskforce report that bleaching damage has affected 93 percent of this iconic ecosystem and tourist attraction.

Corals are colonial animals that exhibit a symbiotic relationship with algae known as zooxanthellae. The corals offer a home to the algae, which give the corals their pigments and perform photosynthesis, thus providing food. However, when temperatures get too warm, the colorful algae leave the coral, rendering it snowy white. A bleached coral is not necessarily dead – zooxanthellae can recolonize a bleached coral once the water temperatures cool down. However, if the coral remains bleached for an extended period of time, it will likely die. Coral bleaching events can affect the community structure of reef fishes and invertebrates that feed on the corals or depend on them for shelter.

Ten Australian research institutions came together to form the National Coral Bleaching Taskforce in November 2015. A survey conducted by the taskforce earlier this year confirmed that the Great Barrier Reef is experiencing the largest bleaching event in its recorded history. The team used planes and helicopters to conduct aerial surveys of 911 individual reefs along the entire 1,400-mile length of the Great Barrier Reef, which stretches along Australia’s eastern coast. Teams of divers have validated the accuracy of the aerial surveys, and are continuing to monitor the ongoing impacts of the bleaching event. The researchers found the coral damage is greatest in the northernmost stretch of the reef, which is closest to the equator. Here, more than 80 percent of the corals were severely bleached, less than 1 percent experienced no bleaching, and more than a third of the corals were dead or dying. In contrast, only 1 percent of the corals in the southernmost stretch surveyed experienced severe bleaching, and 25 percent came through unbleached.

The only other recorded major bleaching events on the reef occurred in 2002 and during the 1998 El Niño. The pattern of bleaching differed during each of these events: in each case, the most severe bleaching occurred in places where the hottest water remained for the longest period of time. During the past two events, 40 percent of the corals did not experience any bleaching. This year, however, only 7 percent of the reef has emerged unscathed. Warm water generated by El Niño is exacerbating the bleaching event caused by rising ocean temperatures due to climate change.

Despite the severity of this event, any mention of the Great Barrier Reef is conspicuously absent from a report released by the United Nations that describes the effects of climate change on dozens of World Heritage Sites. Fearing that reports of damage to the reef would deter tourists from visiting, the Australian government requested that the report’s chapter about the Great Barrier Reef be removed before publication. Australian scientists were surprised and troubled by this move to withhold information about the state of the reef from the public. As Australia’s largest tourism draw, the reef generates $5 billion in income for the country each year. While the reef can recover from a devastating bleaching event, it may take several decades for the slowest growing corals to return. Such events are predicted to become more frequent as the climate warms, and this year provides a clear indication that climate change is the biggest threat that Australia’s natural treasure will continue to face in years to come.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.