Wednesday July 27, 2011

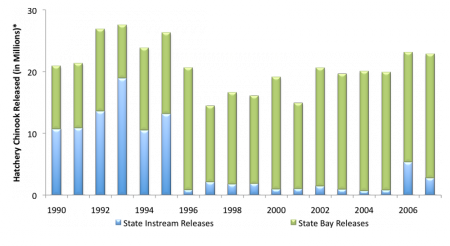

California’s three main state hatcheries (Nimbus-American River, Feather River, and Mokelumne River hatcheries) were constructed to mitigate for production of anadromous Chinook salmon lost as a result of dam construction, but a large majority of these fish never make it back to their natal stream. In an effort to increase survival, approximately 10-12 million state hatchery fish are trucked to the Bay-Delta each year, and in most years they are released into net pens where they are allowed to acclimate before being released into the Bay-Delta. Since some of the hatchery fish are coded-wire tagged (CWT) prior to release, data can be collected on these fish once they are harvested or when their carcasses are recovered after spawning.

California’s three main state hatcheries (Nimbus-American River, Feather River, and Mokelumne River hatcheries) were constructed to mitigate for production of anadromous Chinook salmon lost as a result of dam construction, but a large majority of these fish never make it back to their natal stream. In an effort to increase survival, approximately 10-12 million state hatchery fish are trucked to the Bay-Delta each year, and in most years they are released into net pens where they are allowed to acclimate before being released into the Bay-Delta. Since some of the hatchery fish are coded-wire tagged (CWT) prior to release, data can be collected on these fish once they are harvested or when their carcasses are recovered after spawning.

A review of the CWT data collected from fish released from the Mokelumne River Fish Facility (MRFF) indicates that hatchery fish released into the Bay-Delta contribute a greater proportion to the ocean fisheries compared with those released in river, but contribute proportionally less to escapement in the Mokelumne River compared with fish released into the river (Smith and Workman 2004). Part of the reason for this discrepancy is that the salmon released in the Bay-Delta that do return to spawn are known to have a high rate of straying (e.g. they return to rivers other than their river of origin), which is presumed to be because fish that are trucked to the bay are not given the opportunity to properly imprint on their natal stream. It is believed the straying rate of the fish released in the Bay-Delta could exceed 70% (California Department of Fish and Game and National Marine Fisheries Service 2001).

A review of the CWT data collected from fish released from the Mokelumne River Fish Facility (MRFF) indicates that hatchery fish released into the Bay-Delta contribute a greater proportion to the ocean fisheries compared with those released in river, but contribute proportionally less to escapement in the Mokelumne River compared with fish released into the river (Smith and Workman 2004). Part of the reason for this discrepancy is that the salmon released in the Bay-Delta that do return to spawn are known to have a high rate of straying (e.g. they return to rivers other than their river of origin), which is presumed to be because fish that are trucked to the bay are not given the opportunity to properly imprint on their natal stream. It is believed the straying rate of the fish released in the Bay-Delta could exceed 70% (California Department of Fish and Game and National Marine Fisheries Service 2001).

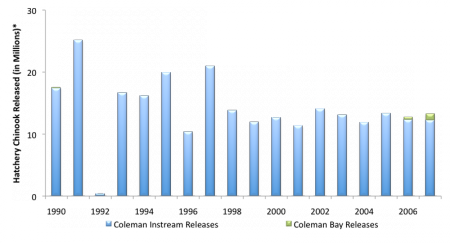

Unlike the state hatcheries, Coleman National Fish Hatchery (CNFH), a federal hatchery operated by U.S. Fish & Wildlife, releases most of their production directly into the river near the hatchery. Studies indicate straying is fairly low when hatchery fish are released into the river and rates are generally less than 10%. On a few occasions, when CNFH released fish into the Bay-Delta (e.g. 1989-1991 because of drought conditions in-river and 2008 to supplement Bay-Delta releases following a drastic decline in salmon) straying was extremely high (75.3%) and comparable to the state hatcheries.

Unlike the state hatcheries, Coleman National Fish Hatchery (CNFH), a federal hatchery operated by U.S. Fish & Wildlife, releases most of their production directly into the river near the hatchery. Studies indicate straying is fairly low when hatchery fish are released into the river and rates are generally less than 10%. On a few occasions, when CNFH released fish into the Bay-Delta (e.g. 1989-1991 because of drought conditions in-river and 2008 to supplement Bay-Delta releases following a drastic decline in salmon) straying was extremely high (75.3%) and comparable to the state hatcheries.

There is a trade-off that California hatcheries make between survival to the ocean and straying of escapement. Data analysis suggests releases in the Bay-Delta result in higher ocean contribution rates and likely higher overall survival than upstream releases. However, as a consequence a high percentage of fish that were released in the Bay-Delta stray and spawn in other rivers, complicating restoration of specific runs and reducing the genetic and life history diversity.