Monday July 2, 2012

Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) exhibit many interesting life history traits. Some of the traits are well known to many of us in California’s Central Valley. For example, they are anadromous (adults migrate from the ocean to spawn within rivers, typically to the river where they were born), they are semelparous (spawn once, then die), and they display diversity in freshwater return run-timings (e.g., fall-, late-fall, winter-, and spring-run). Another interesting trait is their ability to reach spawning maturity at different ages. In Central Valley rivers, returning salmon can range in age from 2 to 5 years, with the most common ages being 3 and 4 year-old adults. In a given year, a portion of the returning salmon will be 2 year-olds, termed “grilse”, having only spent one year in the ocean before maturing. Grilse are overwhelmingly made up of males or “jacks” (female grilse are referred to as “jills”). Grilse are not unique to Chinook salmon, they are found in other salmonid species such as coho and Atlantic salmon.

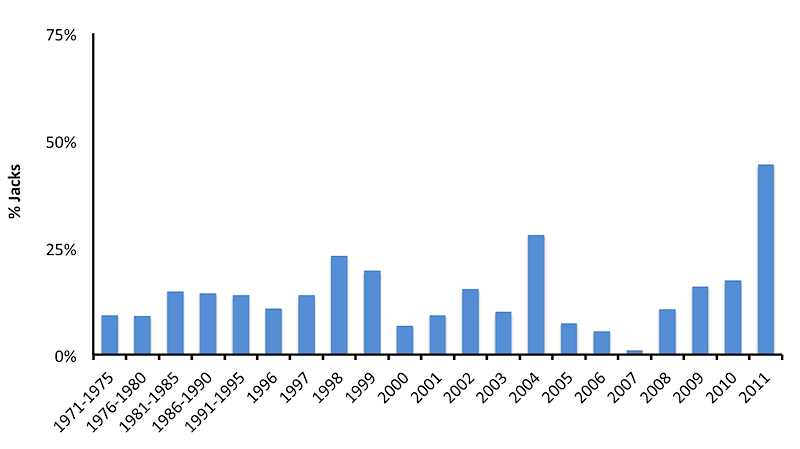

Historically, the number of jacks returning in any given year has provided a general indication of the number of 3 and 4-year old Chinook expected to return in upcoming years. Thus, the Pacific Fishery Management Council uses this information to predict the annual Sacramento River fall-run Chinook (SRFC) abundance (i.e., Sacramento Index) for establishing ocean harvest quotas. However, beginning in 2009, the relationship between the number of jacks and expected returns of 3 and 4-year olds has shifted for SRFC, leading to over-predictions of abundance in recent forecasts (PFMC 2012). The number of SRFC jacks returning in 2011 was the largest on record resulting in jacks representing almost 50% of SRFC abundance, which is the highest percentage of jacks seen in the past few decades (Figure 1).

In periods of increasing abundance of SRFC, the jacks will make up a larger portion of the SI than during the year before. The 2011 increase in jacks as a percentage of returning spawners can be partially, but not entirely explained by increasing overall abundance of SRFC (Figure 1). Other factors that may have contributed to this increase include their parental history and rearing environment, which can affect growth rates and age-at-maturation. In spawning experiments, younger returning males occurred from parental pairings of jacks mated with Age 4+ females compared to pairings of Age 4+ males with Age 4+ females (Hankin et al. 1993). This result may be due to the coupled influences of parental history on growth rates and subsequent growth rate influences on maturity rates. In research comparing growth rates of different parental pairings (Berijikian et al. 2011), the growth rates of offspring sired by jacks were consistently higher than those sired by older males. While this result may seem counterintuitive, it is consistent with many published studies. Individuals with higher growth rates, within a cohort of Chinook salmon (all offspring from a single year), are more likely to mature sooner (at younger ages) compared with individuals with lower growth rates (Ishida et al. 1998; Scheuerell 2005).

Biologists are working to understand the driving force behind these fluctuations in jack abundance, but whether the dramatic increase in percentage of jacks in 2011 is just a reflection of the increasing overall SRFC abundance, an effect of the proportion of jacks successfully mating, or is influenced by another environmental or biological factor, the unusually high percentage has our attention.