Friday August 1, 2014

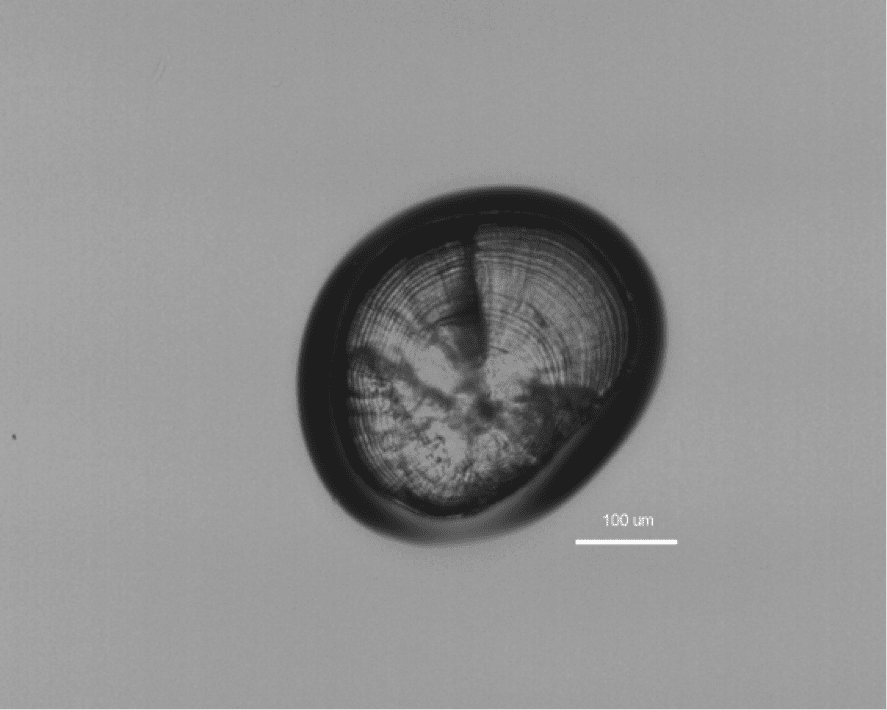

Fishes can hear (and produce) quite a range of sounds, as we discussed in our recent Fish Report, “The Symphony Aquatic.” One of the mechanisms by which fish hear is through bony structures called otoliths, which are also referred to as “earstones.” Pressure from sound waves causes the otoliths to vibrate, which in turn stimulates cilia or hairs that provide sensory cues to the fish. Bony fish have three sets of otoliths: the sagittae, the lapilli, and the asterisci, shown in the photo above. These otoliths aid in balance and hearing. Otoliths also produce growth rings similar to trees, and this characteristic makes them useful in determining the age of a fish (see Rings in their ears).

A variety of fish structures, including otoliths, scales, opercula, spines, and vertebrae, can be used for ageing because their growth trajectory is predictable and verifiable. Otoliths grow by depositing layers around the nucleus, or center, which allows scientists to age a fish by years or even days. Researches can verify these ages by conducting a series of marking events with heat or chemicals, which create unique marks in the otolith of a fish while it is still alive. Once the otoliths are dissected from a fish, these marks are compared to known marking dates and provide scientists with reference points to count how many rings were deposited between the initial and last marking events. When it comes to larval fish, scientists determine ages and growth rates on the order of days. One of our biologists conducted such daily ageing of endangered larval suckers as part of his Master’s thesis.

This thesis explored whether endangered larval suckers inhabited restored wetlands on the Sprague River in Oregon, and how fast they grow in this habitat. Adult suckers typically migrate in spring from Upper Klamath Lake to spawning areas on the Sprague and Williamson Rivers. Three sucker species inhabit this area upstream of Upper Klamath Lake. Both the Lost River sucker (Deltistes luxatus) and the shortnose sucker (Chasmistes brevirostris) are endangered, and the Klamath largescale sucker (Catostomus snyderi) is a species of special concern. There is no hatchery supplementation for these suckers; however, implementation of a controlled propagation program may be used to prevent extinction of the two endangered species (USFWS 2012). Larval suckers are often observed in the wetlands surrounding Upper Klamath Lake, as well as in wetlands on the Sprague River. These wetlands were restored under the Wetlands Reserve Program through the United States Department of Agriculture.

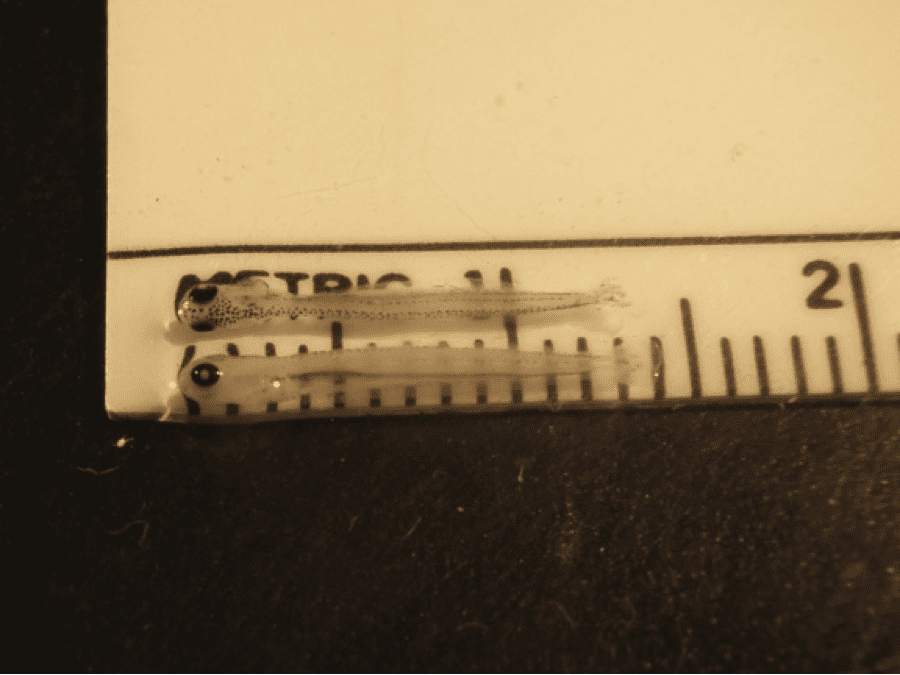

The study included larval suckers ranging from 9–28 mm in length. Larval suckers can be identified to species using a combination of pigmentation pattern and abundance, vertebral counts, and/or myomere counts; however, this proved difficult due to some overlap in characteristics, so the study did not take species into account. Lapilli otoliths were removed using the tip of a pointed scalpel or fine-tipped probe. These otoliths were observed under a microscope, and the number of transitions from light to dark bands was counted to determine the daily age of all specimens (see the photo below). Daily ages ranged from 22 days to 86 days old. Daily age determinations and corresponding lengths were used to calculate approximate growth rates for larval suckers captured in the Sprague River.

Determining a fish’s daily age can provide useful information to fisheries managers to more effectively manage the recovery of endangered species. Growth rates from otolith analysis can be used to compare differences in growth among habitats or regions. This thesis found faster growth rates for larval suckers captured in the Sprague River (wetlands and main stem) than had previously been estimated for larval suckers captured in wetlands surrounding Upper Klamath Lake. Faster growth rates may reveal the importance of the riverine environment for these endangered suckers, and may indicate the need for further restoration of habitats such as wetlands.