Friday January 3, 2025

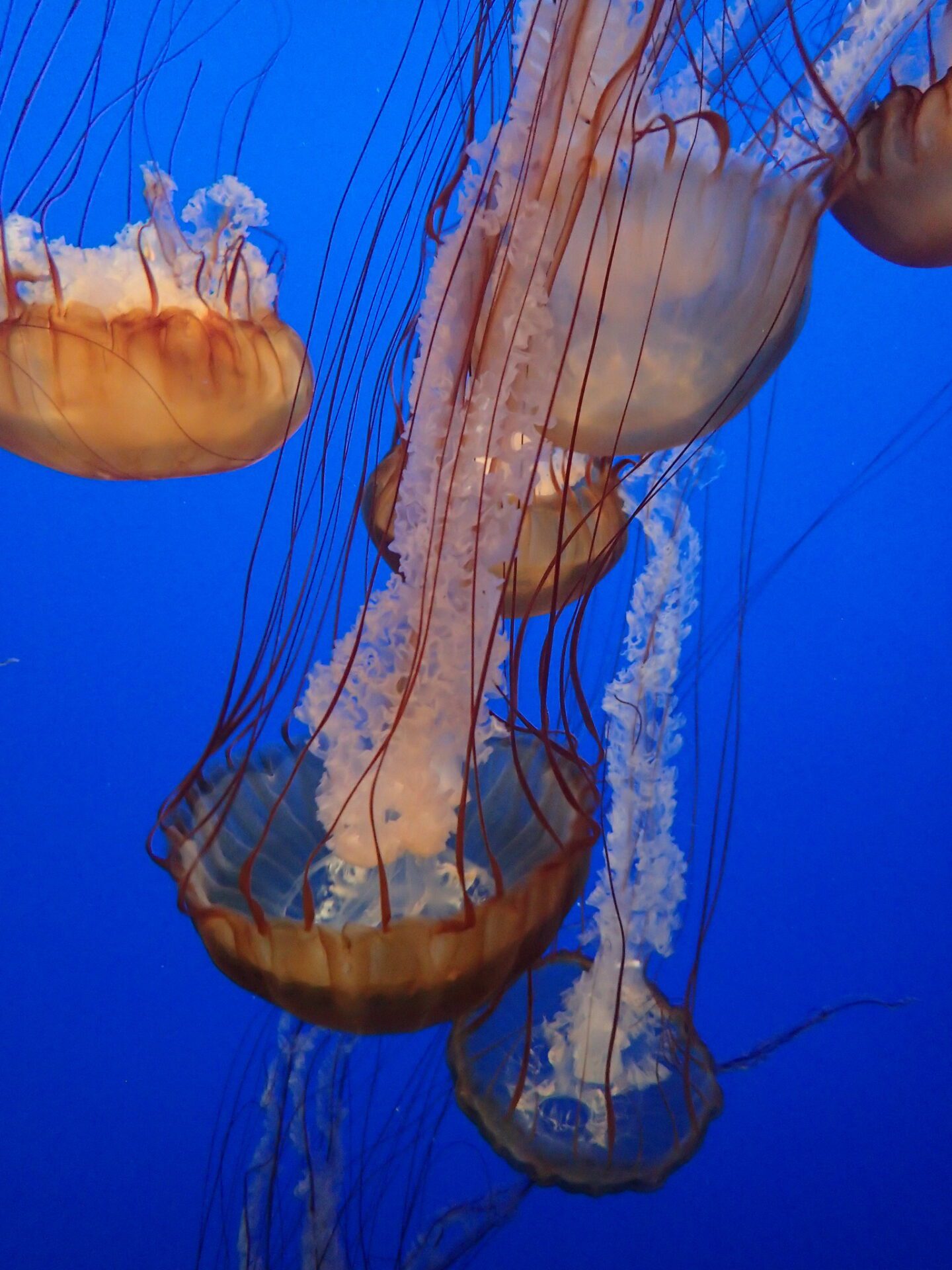

This Flashback Friday, entangle yourself in the stunning life history of the pacific Sea Nettle.

Pacific sea nettles may be spineless, but they are by no means defenseless. These large and beautiful “true jellies” of the Class Scyphozoa are invertebrates, but what Chrysaora fuscescens lacks in backbone is made up for by long stinging tentacles used to paralyze its food before eating. These tentacles can grow as long as 12 feet from underneath the “bell”, which is the top umbrella-shaped portion of a jelly’s body in its adult stage called a “medusa” (shown in this photo). The bell of a Pacific sea nettle can reach 1 to 3 feet in diameter. Despite the sea-nettle’s soft and delicate appearance, it is actually a deadly predator with a carnivorous diet. Their prey largely consists of zooplankton, other jellies, small crustaceans, larval fish and eggs. After the prey has been stung, trailing tentacles bring the food up to the jelly’s gastric cavity (or “stomach”) for digestion.

While these jellies are not particularly fast, they do move around quite a bit. Depending on the time of year, they live at different depths in the ocean. During summer and spring, they live deeper down, and during fall in winter they live closer to the surface. The Pacific Sea-nettle is generally found in the coastal waters of the West Coast, along California (such as the Monterey Bay) and Oregon, although they can also be spotted in the Gulf of Alaska and even Japan. While the sea nettle is itself a predator, the species is also food for of sea turtles, sunfish, and seabirds. One notable predator is the leatherback turtle, which visits Monterey Bay to feed on sea nettles along with other jellyfish and salps.

The sea-nettle reproduces using a method called broadcast spawning, in which eggs are released and fertilized outside the jelly’s body. The fertilized eggs then hatch into small larvae called planulae. Despite their large adult size, these invertebrates don’t live very long: generally 6 months to a year from hatching to the end of their life cycle. Their numbers are largest during fall and winter times, where they can sometimes occur in huge blooms (although interestingly, a group of jellies is known as a “smack”). Human modifications to ocean conditions are allowing jelly populations like that of the Pacific sea-nettle to expand, reflected by an increase in such blooms. This is partially due to an increase in temperature of the coastal waters that they inhabit, as well changes in nutrients from runoff. Sea nettles are not only beautiful and majestic sea creatures, but they play an important role in their ecosystem due to their impact as a predator by serving as a source of food for more vulnerable species. While their population appear to be faring well, understanding their important roles in nature can help us recognize the way organisms interact with each other and respond to different environmental changes. To experience the mesmerizing motion of the Pacific sea nettle, check out the live jellyfish cam hosted by the Monterey Bay Aquarium (where one of FISHBIO’s biologists took the photo above).

This story was written by Nicholas Seyfried for an internship with FISHBIO through the UC Santa Cruz Environmental Studies Department.