Friday June 5, 2015

Scientists working to save coral reefs might dream of growing rare corals in a laboratory, then transplanting them to damaged reefs as a way to restore the ecosystem. According to a recent study in BMC Ecology, researchers working in Curaçao are getting close to making this dream a reality by growing an important coral in the lab for the first time. Dendrogyra cylindrus is a branching Caribbean pillar coral that plays a key role on reefs: it provides habitat for fish, and helps break up large waves that approach shore from the ocean, protecting Caribbean coastlines. Unfortunately, this coral is also rare and considered under threat by human activities and changing climate. Populations of branching coral colonies are often genetically identical, making them more susceptible to being wiped out by threats like diseases. Being able to grow juvenile corals in the lab and successfully transplant them back into reefs would also increase the genetic diversity of the population, making it more resilient to future threats.

The scientists started by collecting eggs and sperm from the corals. Pillar corals are broadcast spawners, meaning they release eggs and sperm into the water to mix on their own, and a small percentage of the eggs are fertilized. Because D. cylindrus only spawn a few nights a year, this was more difficult than it sounds: the researchers had to try to schedule their collection around the times they thought the corals would be most likely to spawn, which turned out to be 100 minutes after sunset, exactly three nights after the August full moon (corals clearly keep a strict schedule). They collected eggs using nets and funnels placed over the female colonies, and used syringes to manually collect sperm.

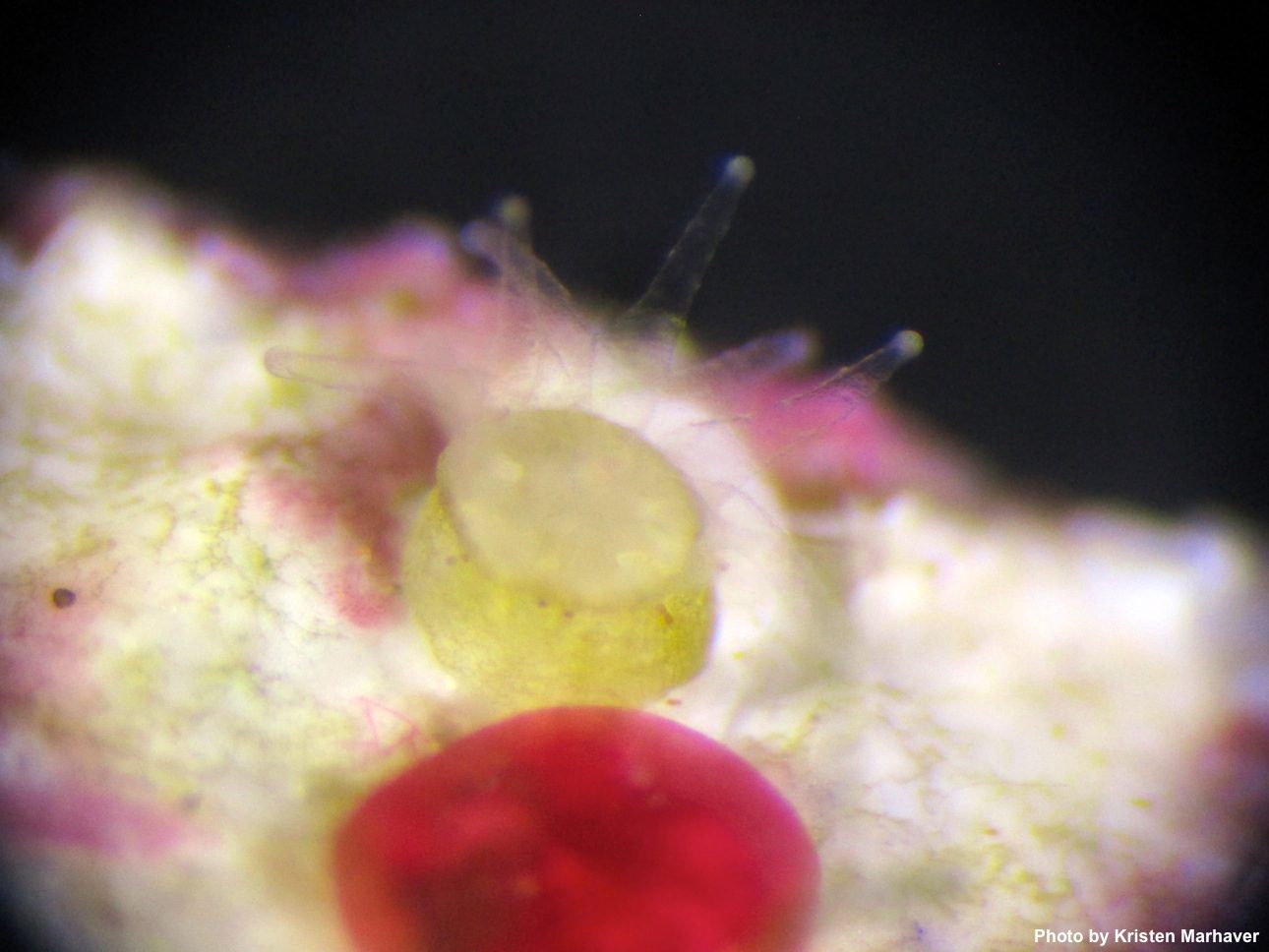

The researchers then mixed the collected sperm and eggs to fertilize them, trying the process both underwater and on shore. Some of the eggs were successfully fertilized, which allowed the scientists to raise them into larvae in a lab, making this the first time swimming larvae of D. cylindrus have ever been seen. The larvae successfully settled in tanks in the lab, where they survived for more than seven months. The researchers’ next step is to attempt to transplant the juvenile larvae to reefs in Curaçao and see if they survive. They believe that juvenile coral may be able to adjust to changing environments better than adult coral, so introducing new juveniles to the reef may help make this vulnerable ecosystem more resilient to climate change and other human impacts (Marhaver et al. 2015). The researchers also hope to do further lab research to test the coral’s response to factors that may be contributing to their decline, such as water quality, contaminants, and the presence of animals and bacteria, with the hope to improve future conservation efforts.