Monday May 6, 2024

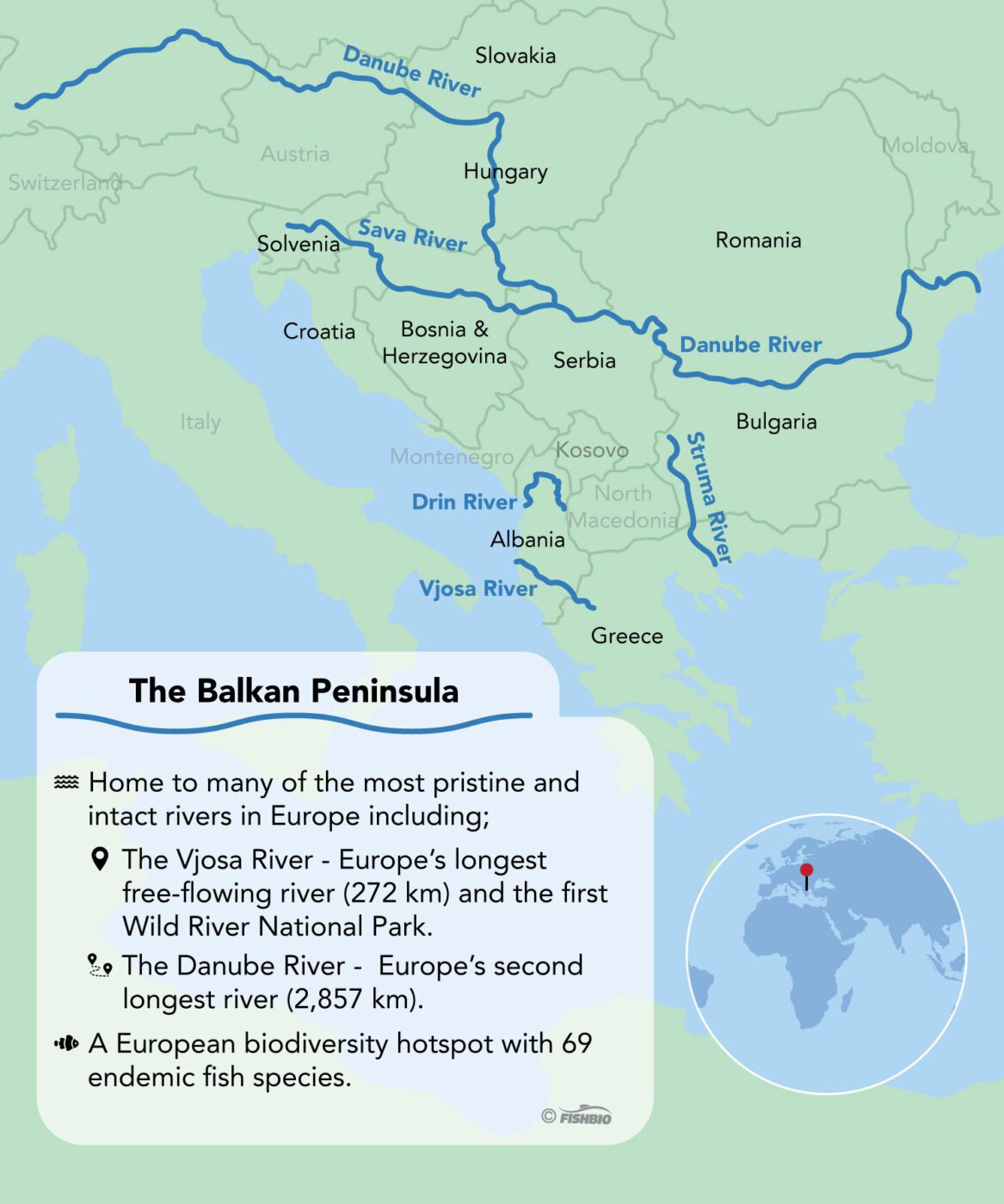

The Balkan Peninsula is renowned for its pristine beaches, early human and neanderthal settlements, and rich architectural history stemming from ancient Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman influences. The Balkan region encompasses nearly 550,000 square kilometers of land in Southeastern Europe between the Adriatic, Mediterranean, Aegean, and Black Seas. Recognized as the Blue Heart of Europe, the Balkan Peninsula is home to the highest density of pristine and intact rivers, including the Vjosa River, one of the largest undammed rivers in all of Europe. Nearly 80% of the rivers in the Balkans have been ranked from acceptable to pristine compared to only 40% across Europe, with the rivers of Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands among the most heavily impacted.

Štrbački Buk Waterfall on the Una River, a tributary of the Sava River that forms the border between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Balkan watersheds are characterized by jewel-tone waters and scenic waterfalls, granite, gneiss, and limestone rock formations, and numerous subterranean rivers snaking unseen through the limestone karst of the region. This unique convergence of characteristics has led the Balkans to be one of the main centers of biodiversity in Europe. Its rich collection of diverse plants and animals include six sturgeon species, a blind cave salamander (Proteus anguinus), and the critically endangered Balkan lynx (Lynx lynx balcanicus). Freshwater Balkan ecosystems are home to 69 endemic fish species and provide habitat for 28% and 40% of endangered European freshwater fish and mollusk species, respectively.

Loss of connectivity and degradation of freshwater habitat threaten this critically important refuge habitat and could have dire consequences for many at-risk and endangered European fish species. For example, the largest non-anadromous salmonid in Europe, the huchen (Hucho hucho), also known as the Danube salmon, has already been lost from a third of its historic range, and loss of habitat in the Balkans is projected to result in a 70% population loss for the species. Additionally, five of the six sturgeon species in the Balkans are critically endangered and anadromous, meaning that these fish need long reaches of unfragmented rivers connected to salt-water habitats to properly carry out reproduction. Thus, any loss of connectivity in the Balkan region will likely result in further species decline, extirpation, or extinction.

A painting of a huchen from Unsere Süßwasserfische, or in English “Our Freshwater Fish” (Quelle & Meyer 1913).

Although Balkan rivers are highly valued and remarkably intact compared to other European rivers, thousands of proposed development projects in the region pose an impending threat to the integrity of the river ecosystem and the native biodiversity it supports. As of 2022, there were over 8,000 hydropower plants planned for construction in Europe. Nearly 3,000 of these were slated for the Balkan region, 40% of which were proposed in protected areas. There are currently 1,726 hydropower dams operating in the Balkans, and successful development of the proposed dams would result in over a 2.5-fold increase in hydropower plants in this area. In stark comparison, there are only about 1,500 hydropower dams in the entire United States. These hydropower plants have been proposed to meet increasing energy demands while also providing jobs to locals and attracting investments to the Balkan region. However, each of these proposed dams poses significant risks to endemic and at-risk species in the Balkans and challenges even the safety of those living in protected areas.

The Rivers of the Balkan Peninsula.

Increased interest in establishing hydropower plants in the Balkans has been met by grass-roots opposition in many countries throughout the region. Opposition organized by Women of Kruščica in Bosnia-Herzegovina halted development of a dam on the Kruščica River through a triumphant court case ruling that the development lacked sufficient community consultation. Similar court cases have been won throughout the region, and numerous community opposition movements towards protecting these pristine waters are in progress. In 2019, the Krupa River in Croatia was given permanent protection under a “cultural heritage” designation, and Zeta River in Montenegro was designated a Nature Park. Notably, the Vjosa River became the first Wild River National Park in Europe in 2023 through collaboration of the Albanian government with local and international experts, nonprofits, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The confluence of the Sava and Danube in Belgrade, Serbia. Photo by Peter Kurdulija.

With the current verve for hydropower development, Europe’s most pristine waterways in the Balkans face an uncertain future. However, the world is watching closely as community-led movements seek to counter hydropower development. River-first approaches as modeled by community organizations on the Vjosa River have laid the groundwork for others to follow in protecting important river ecosystems – maintaining community relationships with local resources and developing avenues for local income through tourism expound an inspiring and productive conservation strategy. These community organizers have ensured that future management of Balkan Rivers will consider the needs of communities, governments, and natural resources to ensure adequate protection of native fisheries and biodiversity while balancing needs of local peoples.

Header Image: Forest and lakes in Krka National Park, Croatia.

This post is part of our Wild Rivers series, highlighting the world’s last remaining undammed and free flowing rivers in celebration of World Fish Migration Day. Learn more at fishbio.com/category/wild-rivers