Monday August 12, 2013

It’s hard to believe based on the sizes of their populations today, but long ago spring-run Chinook salmon (spring-run) were the most abundant run of Chinook salmon in California’s Central Valley. Historically, spring-run migrated upstream starting in late March, held out through the summer in the cold-water pools that once existed in the upper reaches of the basin, then spawned during late summer and early fall. During the last century, approximately 95% of this critical cold-water habitat has been lost due to mining, water diversions, and dam construction (Yoshiyama et al. 2001). As a result, the once abundant Chinook salmon population experienced a drastic decline in the Central Valley. The continuous degradation of spawning and rearing habitat, ongoing fishing pressure, and an increase in predator populations has lead to the near extirpation of spring-run in all rivers in the Central Valley. In 1999, spring-run were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

In 1967, the Feather River Hatchery commenced spawning Chinook salmon to mitigate the loss of habitat resulting from the completion of Oroville Dam – only eight miles of usable spawning habitat remain on the river. Feather River is presently the only hatchery in the Central Valley with a spring-run program, and they currently spawn and tag more than 2 million of the fish annually (Buttars 2012). However, due to the overlap in spawn timing between spring-run and fall-run, the two runs have interbred and are now genetically indistinguishable (HGMP 2010). Genetic analysis indicates that “spring-run” Chinook on Feather River are in fact fall-run fish with “spring-running” behavioral traits.

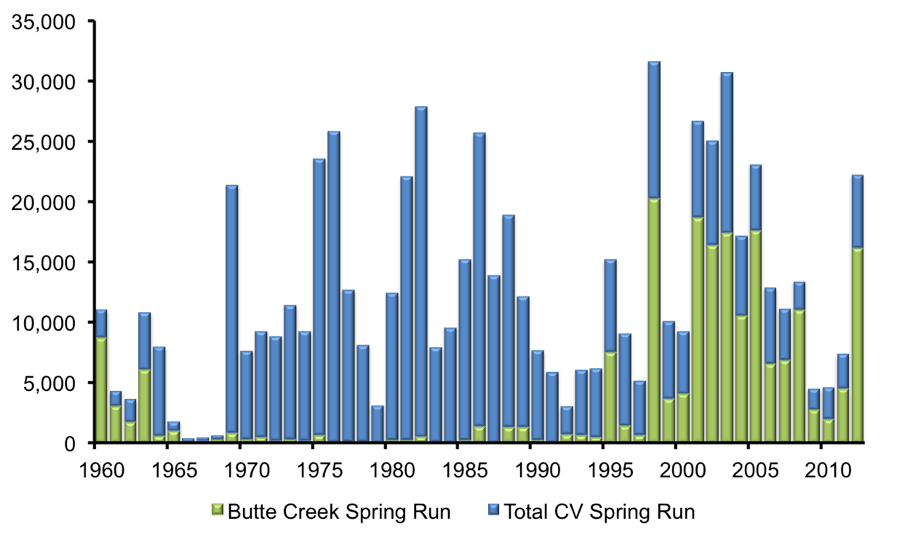

The Butte Creek watershed, like most watersheds in the Central Valley, has been transformed through levees and water diversions since the mid-1960s. Prior to 1960, Butte Creek supported a run of more than 6,000 spring-run, but a reduction in flow and numerous fish barriers decreased the population to only a few hundred fish in most years. Between 1977 and 1979, the Butte Creek spring-run population declined to just 238 fish, and genetic analysis confirms that the diversity of the gene pool has diminished as a result (Grand Tab 2013). In the early 1990s, fish passage improvement projects and baseline flow increases lead to a significant increase in the number of fish returning to Butte Creek, which now supports the largest naturally spawning spring-run population in the Central Valley (see Spring into action!). However, the “bottlenecking” of the gene pool that occurred in the ’70s has significantly jeopardized the genetic integrity of spring-run on Butte Creek – they are currently the least diverse of the Central Valley’s spring-run populations, and therefore have a limited ability to adapt to environmental change.

Managing the future of spring-run is a challenge. There are currently efforts to restore spring-run to the San Joaquin River, which has been dry in most years since the completion of Friant Dam in 1942. The goal of the project is to establish a self-sustaining population of spring-run by 2024 using hatchery fish as surrogates. Now that habitat for spring-run is limited to the reaches below Friant Dam and the genetics of the population have been compromised, reintroduction will be a difficult task – nearly as difficult as restoring the entire river itself.

Figure 1. Spring-run Chinook salmon observations on Butte Creek (green) as well as the entire Central Valley (blue) (data from GrandTab report 2013).

Figure 1. Spring-run Chinook salmon observations on Butte Creek (green) as well as the entire Central Valley (blue) (data from GrandTab report 2013).

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.