Monday August 22, 2016

Winter-run Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) are the most endangered of California’s four salmon runs. These salmon return to freshwater in the winter, and historically sought refuge in the cooler headwaters found in Northern California to survive the state’s blistering summers. Now that dams block access to their historic habitats, winter-run salmon have to make do in significantly altered river reaches much further downstream. Helping this race of salmon survive in a novel environment requires an elaborate balancing act of temperature controls to provide suitable conditions. As the state continues to endure a historic drought, the management of Lake Shasta in northern California to support winter-run on the Sacramento River has become a complex process of give and take. Poor storage levels over the past several years have led to difficult management decisions regarding water allocation, river discharge levels, maintaining the reservoir’s cold-water pool, and the in-river water temperatures that result from reservoir discharges. All of these factors are integral to the survival and persistence of the winter-run Chinook salmon population in the Sacramento River.

Winter-run Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) are the most endangered of California’s four salmon runs. These salmon return to freshwater in the winter, and historically sought refuge in the cooler headwaters found in Northern California to survive the state’s blistering summers. Now that dams block access to their historic habitats, winter-run salmon have to make do in significantly altered river reaches much further downstream. Helping this race of salmon survive in a novel environment requires an elaborate balancing act of temperature controls to provide suitable conditions. As the state continues to endure a historic drought, the management of Lake Shasta in northern California to support winter-run on the Sacramento River has become a complex process of give and take. Poor storage levels over the past several years have led to difficult management decisions regarding water allocation, river discharge levels, maintaining the reservoir’s cold-water pool, and the in-river water temperatures that result from reservoir discharges. All of these factors are integral to the survival and persistence of the winter-run Chinook salmon population in the Sacramento River.

The Sacramento River winter-run Chinook was originally listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act in 1989, and was elevated to endangered in 1994. Prior to the construction of Shasta and Keswick Dams, winter-run Chinook salmon could be encountered in the Little Sacramento, McCloud and Pit rivers; however, their current range has been constricted to the area just below Keswick Dam on the Sacramento River near Redding, Calif. The 44-mile stretch of the Upper Sacramento River between Keswick Dam and Red Bluff represents the only suitable habitat where winter-run Chinook can withstand the summer heat because of cool water released from Lake Shasta. Ironically, Shasta Dam, the very structure that cut off winter-run from their historical habitat, now provides the deep cold-water pool necessary for maintaining the downstream water temperatures the fish need to survive.

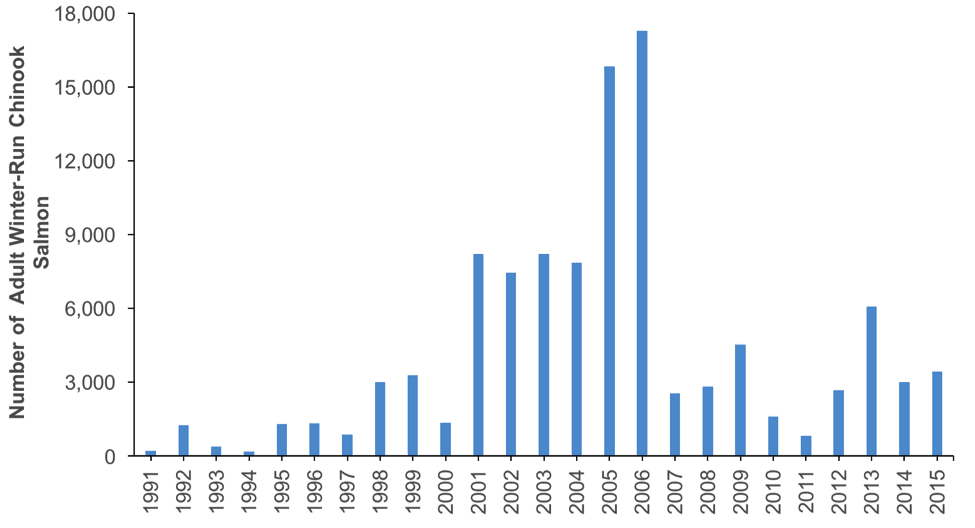

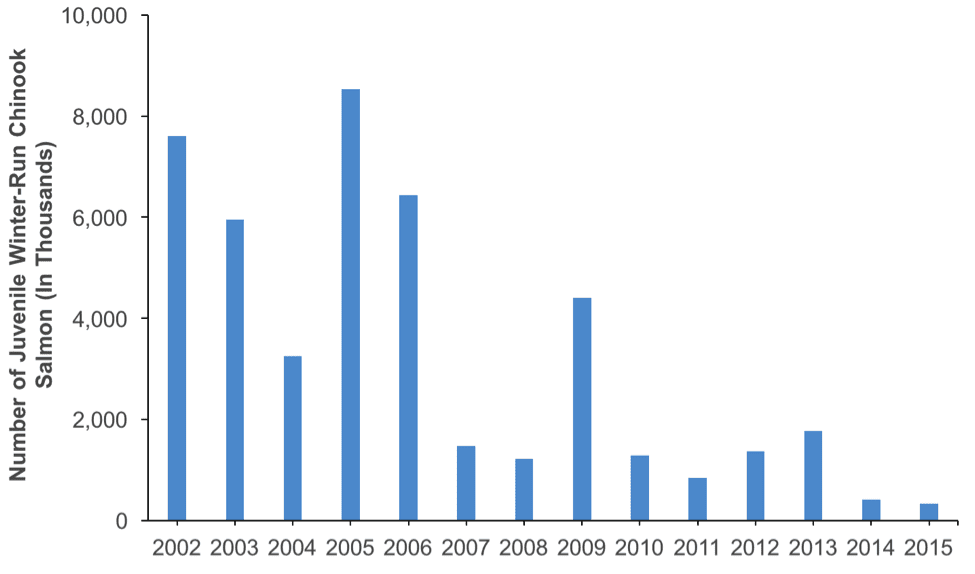

As a result of losing access to their historic habitat, the winter-run population crashed from an estimated 87,000 spawning adults in the late 1960s to fewer than 200 in the early 1990s. The population began to rebound in recent years, averaging 3,207 spawning adults (827–6,084) between 2010 and 2015 (Figure 1). Due to the efforts of management groups such as the Sacramento River Temperature Task Group (SRTTG), recent juvenile outmigration has been strong, averaging an estimated 1.9 million individuals passing through Red Bluff Diversion Dam between 2009 and 2013 brood years. However, the recent average estimated outmigration numbers have substantially declined as a result of critically dry water years in 2014 and 2015 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Annual Winter-Run Chinook salmon adult escapement within the Sacramento River system. Data source: CDFW 2016.

Figure 1. Annual Winter-Run Chinook salmon adult escapement within the Sacramento River system. Data source: CDFW 2016.

The cool water stored behind the 602-foot tall Shasta Dam is allocated to various resources downstream by a novel distribution system. In order to maximize and conserve the pool of cold water cached away, the Bureau of Reclamation constructed an $80 million, 9,000-ton Temperature Control Device at the upstream face of the dam in 1997. This wall has a series of gates at 720, 800, 900, and 1,000 feet above sea level, which managers can open or close to determine the depth, and therefore temperature, of water released from the reservoir. Management groups, like the SRTTG, are then able to use this reserve to attempt to maintain a 56°F daily average temperature on the Sacramento River at varying compliance locations based on the National Marine Fisheries Service 2009 Biological Opinion on the management of salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon.

Figure 2. Annual estimated passage of unmarked juvenile winter-run Chinook salmon at the Red Bluff Diversion Dam by brood-year (BY). *2013 Winter-Run passage value estimated using a monthly mean for period between Oct. 1 and Oct. 17 due to government shutdown. Data source: USFWS 2016.

Figure 2. Annual estimated passage of unmarked juvenile winter-run Chinook salmon at the Red Bluff Diversion Dam by brood-year (BY). *2013 Winter-Run passage value estimated using a monthly mean for period between Oct. 1 and Oct. 17 due to government shutdown. Data source: USFWS 2016.

The 56°F temperature threshold is critical to both spawning and rearing winter-run Chinook salmon. When daily average water temperatures begin to climb over the threshold, the percentage of eggs expected to survive rapidly declines. In 2015, errors in estimating the volume of cold water in Lake Shasta caused the cold-water pool to be depleted by mid-November. Because too much cold water was released early in the season, downstream temperatures climbed as high as 62°F in fall 2015. Typically, about 25 percent of winter run eggs survive to become fry, but as a result of the elevated water temperatures, scientists estimate only about 5 percent of fry survived in 2015. There is concern that should these low population numbers of winter-run Chinook continue, closures may be imposed on the fall-run salmon fishery in coming years to avoid any unintentional catch of winter-run. Amid warm temperatures and a short supply of cool, clear water, the annual balancing act to meet the needs of people and the environment becomes an increasingly confounding and contentious task.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.