Monday November 3, 2025

If you have ever walked along the shore and noticed long, wavy strands of kelp with thick bulbs lying on the sand, you have likely encountered bull kelp – one of the fastest-growing organisms on the planet. Reaching lengths of up to 100 feet in a single season, bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) forms vast underwater forests along the Pacific coast, especially off California. These forests are crucial habitat for marine life, providing food, shelter, and breeding grounds for numerous species.

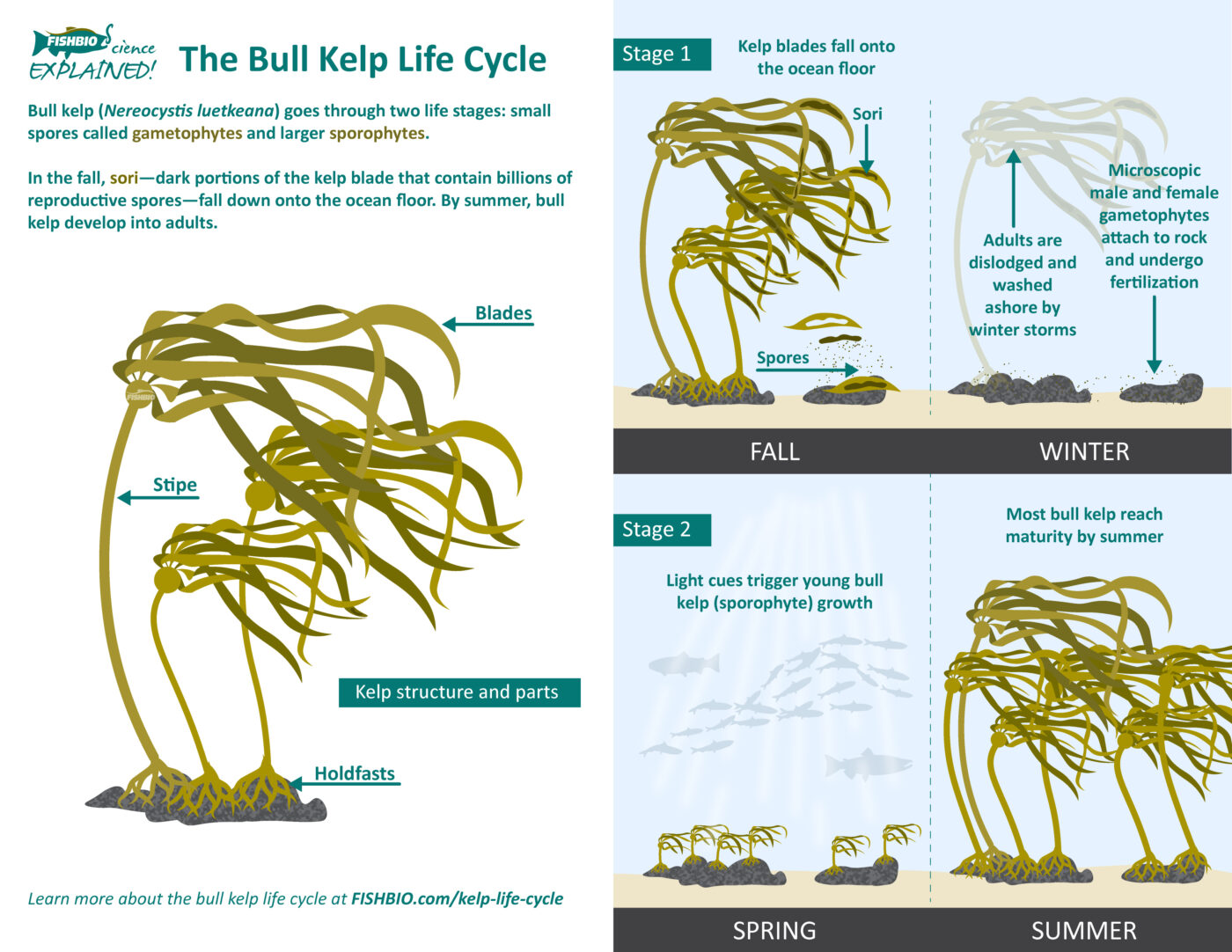

Despite its plant-like appearance, bull kelp is not a plant at all. It belongs to a group of brown macroalgae, and lacks many of the internal structures true plants have. For instance, instead of roots, bull kelp has holdfasts – clinging structures that anchor it to the rocky seafloor. Unlike roots, holdfasts do not absorb nutrients. Similarly, its stipe (which looks like a stem) does not transport water or nutrients internally. While kelp have blades that resemble leaves, they lack the structures and veins that true plant leaves contain. Still, like plants, bull kelp use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to metabolize and grow.

Something that makes bull kelp remarkable is its complex and unique life cycle, which includes two very different stages: a developing phase that happens at the microscopic level and an adult phase. At the end of each summer, mature kelp blades develop sori, which are dark brown patches filled with thousands of microscopic reproductive cells called spores. These sori break off and fall, releasing spores into the ocean current. Eventually, they settle onto the seafloor – ideally in well-lit, nutrient-rich areas – where they begin the next stage of life. After settling, the spores don’t immediately grow into kelp. Instead, they first develop into minuscule gametophytes that are nearly invisible to the naked eye. These microscopic forms are either male or female and play a crucial role in reproduction. While on the seafloor during winter, male gametophytes release sperm, which swim toward the eggs produced by female gametophytes. When fertilization occurs, the result is a baby bull kelp called a sporophyte. If conditions are right, the young sporophyte grows rapidly, triggered by light cues in the spring. Bull kelp can grow more than a foot per day, racing toward the sunlit surface where it can photosynthesize more efficiently. By the next summer, it reaches full maturity and begins producing sori of its own, repeating the life cycle.

Meanwhile, the parent kelp, having completed its role, often detaches from the seafloor and floats ashore, becoming a tangled mess lying in thick, slippery bundles on beaches. Even in this final stage, bull kelp provides shelter and food for creatures on land (primarily invertebrates) until it fully breaks down. While this reproductive cycle is common to most large kelp species, it is not universal. Other types of brown algae, particularly those not considered true kelp, have identical gametophytes and sporophytes or dormant gametophytes that will wait for ideal conditions before growing.

In addition to its ecological role, bull kelp is a carbon dioxide-capturing powerhouse. Kelp forests can absorb up to 20 times more carbon dioxide per acre than land forests, helping to reduce ocean acidification and mitigate climate change. Unfortunately, these incredible organisms are in decline. Between 2014 and 2019, Northern California saw more than 90% of its bull kelp vanish. Rising ocean temperatures and rapidly growing sea urchin populations have devastated these underwater forests. Without healthy kelp, entire ecosystems can unravel. Still, there’s hope. As scientists learn more about the kelp life cycle and its vulnerabilities, efforts are underway to restore damaged habitats and support urchin predators. New research is exploring the reintroduction of sea otters to help revive kelp populations in British Columbia and Southern California. Once hunted to near extinction for their fur, sea otters are a keystone species whose return can control urchin populations, giving kelp forests a fighting chance for recovery.

Understanding how bull kelp grows, reproduces, and interacts with its environment is key to protecting this species and the countless others that rely on it. So next time you see a strand of kelp washed up on the beach, remember: it’s more than just seaweed. It’s the final chapter in an incredible story of survival, transformation, and renewal beneath the waves.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.

This story was written by Ananya Karthikeyan for an internship with FISHBIO through the UC San Diego Academic Internship Program.

Header Image Caption: A graphic illustrating the different life stages of bull kelp.