Wednesday March 6, 2019

A recent study revealed that insect species have experienced a staggering worldwide decline over the past 40 years (Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys 2019). Researchers compiled decades of long-term insect surveys and found that among the most affected insects are those that spend a portion of their life cycle in fresh water. These include the groups Odonata (dragon and damselflies), Plecoptera (stoneflies), Trichoptera (caddisflies), and Ephemeroptera (mayflies). In this blog series we will delve deeper into the declines of these insects, and their importance in aquatic ecosystems.

First, we focus on the Order Odonata, the dragonflies and damselflies. These flamboyant acrobats of the sky are sure to catch the eye of anyone on a streamside stroll. Easily distinguished from one another by the manner in which they hold their wings (dragonflies lay them flat and damselflies fold them back), both dragon and damselflies are voracious predators. The appetites of these bejeweled insects serve humans well, as they reduce the abundance of pest species like mosquitoes. Even before they emerge from the water to rule the skies as aerial predators, they prowl the streambed as nymphs, consuming other invertebrates, and in some cases even vertebrates like small fish or tadpoles. They play multiple roles in the aquatic food web, often becoming prey themselves for larger fish. As both predator and prey, dragonflies and damselflies are important inhabitants of freshwater ecosystems, and this makes their apparent global decline all the more alarming.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently lists 118 aquatic insect species as endangered, and of these an overwhelming 106 belong to Order Odonata. IUCN estimates also suggest that 10% of all Odonata species are at risk of extinction, and further research indicates that this may be a conservative estimate due to gaps in monitoring data for certain regions of the world. A study of 45 different sites in California and Nevada compared records from 1914–1915 to data from modern surveys and found that 65% of all recorded dragonfly and damselfly species had declined. Other regions aren’t faring much better, as 22 of Europe’s 138 species and subspecies are threatened, 57 of Japan’s 200 species are declining, and of South Africa’s 155 species, 13 are declining and four are extinct. These declines have mostly affected species that specialize in particular habitats, and in some cases their decline has allowed an influx of generalist and migratory species to move in, which has decreased diversity by making species assemblages more similar to each other.

Many factors are believed to be contributing to the startling damsel and dragonfly downfall throughout the world, including the use of synthetic pesticides and climate change. However, the main stressor seems to be habitat loss and degradation. As cities grew and agricultural production intensified over the past century, freshwater habitats were fundamentally changed. As many streams lost some of their unique features, the diverse communities of aquatic plants that Odonata relied on to complete their life cycle disappeared, and in many cases only generalist species were able to survive in the human-created environments. Studies on the status of these insects seem to predict a dire future, but there are steps that can be taken to help. The restoration of natural habitat, and in particular the creation of urban greenspaces and gardens can help provide valuable refuges for native species. The Xerces Society has even published a guide on how to create backyard ponds that favor native dragonflies and damselflies. By conserving these incredible insect predators, we can ensure they continue to play their essential part in freshwater ecosystems and provide valuable pest control services free of charge.

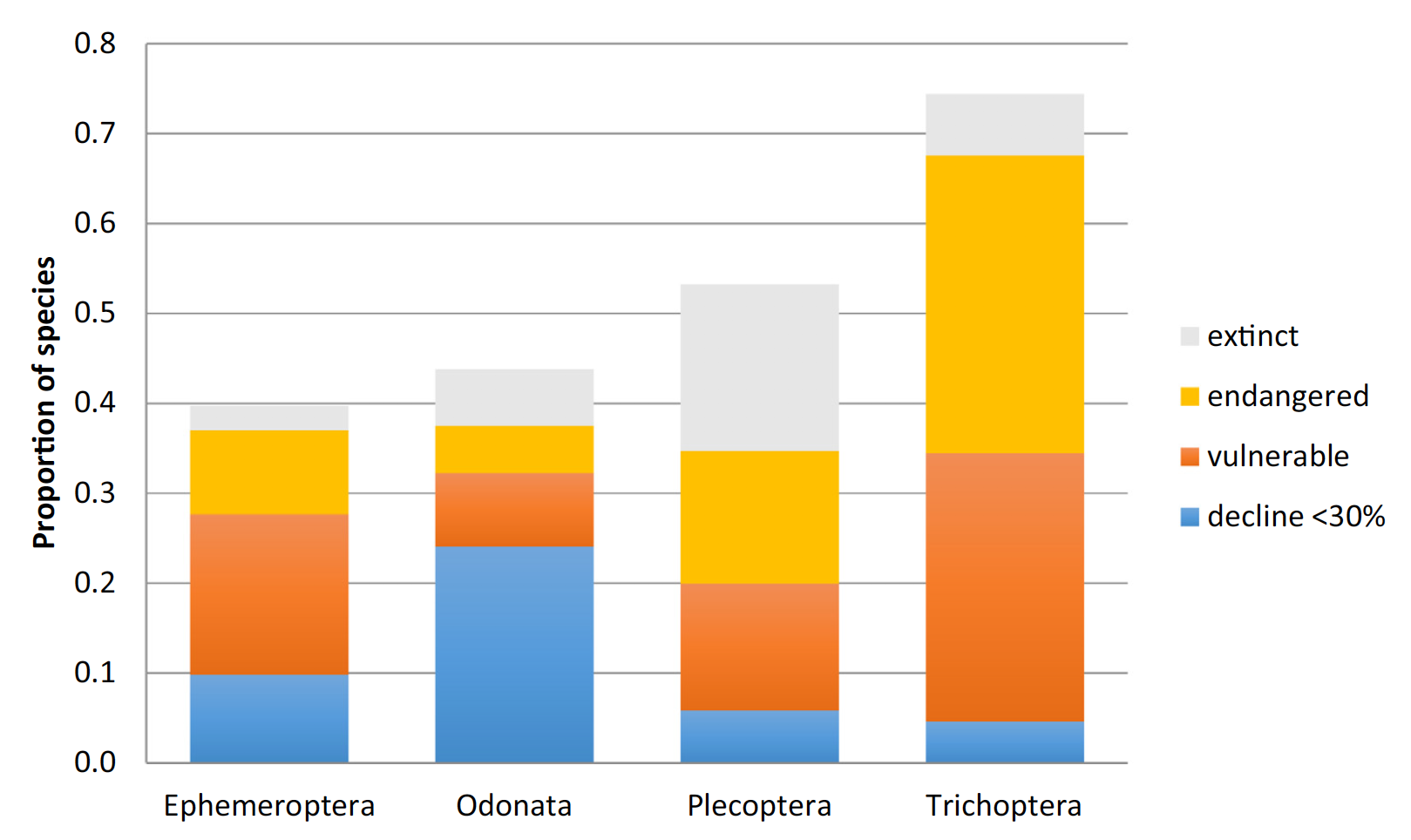

Graph from Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys 2019 showing the proportion of aquatic insect species in decline or locally extinct.

Graph from Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys 2019 showing the proportion of aquatic insect species in decline or locally extinct.