Monday August 14, 2023

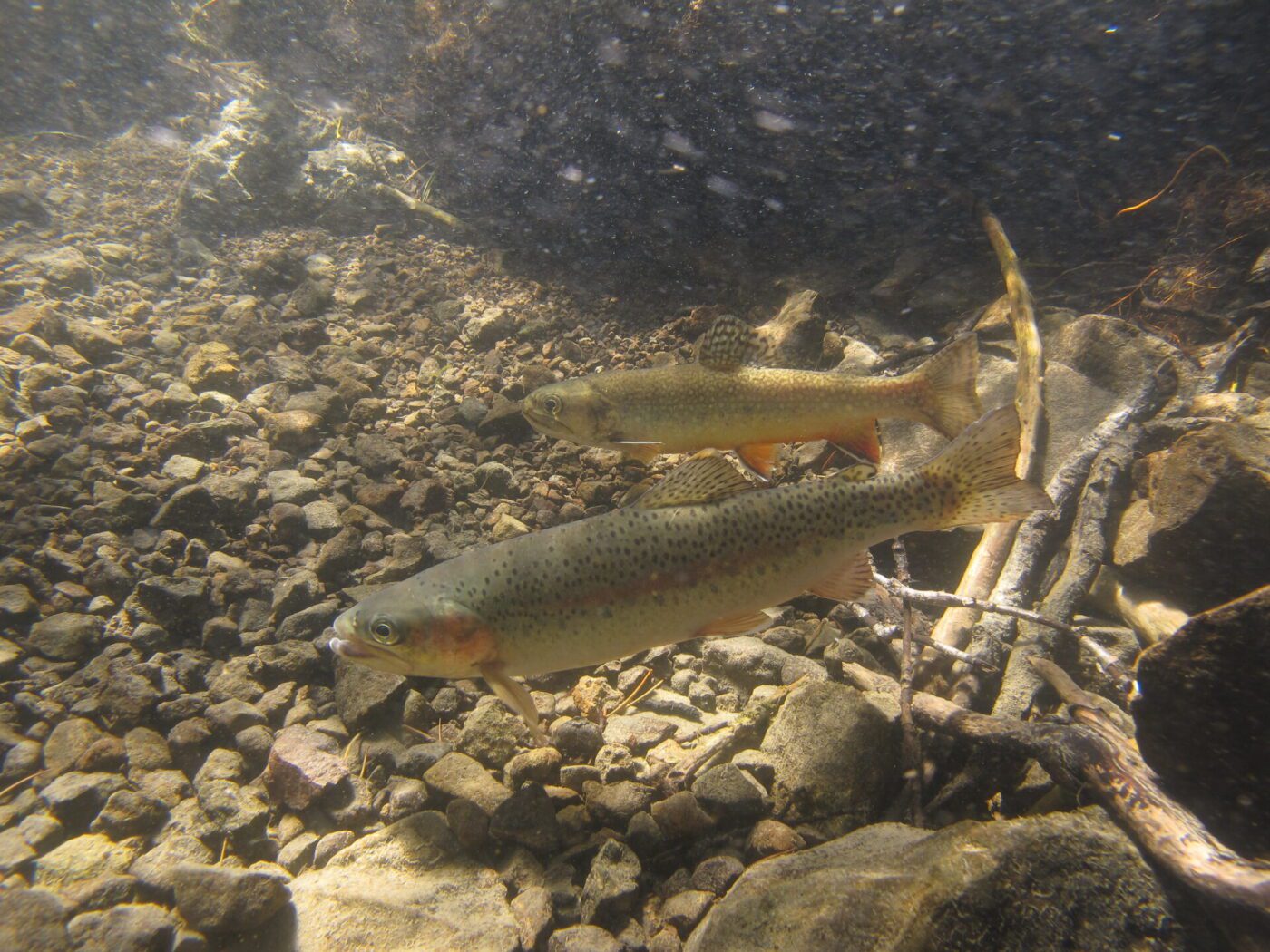

Brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) are, arguably, one of the most popular game fishes for their unique markings, sweet taste, and penchant to strike a lure more readily than other trout. Although they boast the trout name and are in the Salmonidae family with trout, they are actually part of the char (Salvelinus) genus which is characterized by dark bodies with light spots rather than the light bodies with dark spots of the trout genus. Yellow spots with a vermiculation (wavy, maze-like lines) pattern adorn the dark olive-green backs of the brook trout, and blue halos encircling red spots mark their sides. They also have striking orange-red pectoral, pelvic, and anal fins with white leading edges, making them stand out even further from the trout crowd.

Brook trout are native to most of eastern North America, spanning as far south as the mountainous terrain of northern Georgia to the Hudson Bay in Canada. They are so popular in North America that nine states and Nova Scotia call them their state or provincial fish – making them the most popular state fish! This popularity launched them, literally, into waters far beyond their native range including those in Europe, Argentina, New Zealand, and the western United States. In remote alpine lakes in the western U.S., brook trout were extensively stocked to provide sustenance to those enjoying the backcountry – by getting dropped from airplanes! Brook trout were first introduced to California in the 1870s, and soon thereafter, large numbers were raised and planted in a variety of streams and lakes across the state. Brook trout, like many other introduced sport species, are now widespread and established in the spring-fed headwater streams and isolated mountain lakes of the Sierras.

Unfortunately, introducing fish into waters outside of their native range is not without consequences. Nonnative fish can impact native species through predation, competition, or hybridization. Many of the alpine aquatic habitats where brook trout have been stocked were originally fishless. Their introduction has altered the ecology of these habitats by changing nutrient cycles and negatively impacting native amphibian and invertebrate populations through predation. Because brook trout have similar ecological niches to native trout species, they compete over the same habitats and food resources. Bull trout (S. confluentus) are a native char in the Pacific Northwest and populations can be compromised by hybridization with brook trout.

With the knowledge that introduced brook trout can negatively affect native trout populations and aquatic ecosystems, biologists have attempted to minimize their impacts while still providing fishing opportunities to the public. To protect endangered amphibians resident in historically fishless habitats from predation, it is necessary to completely remove brook trout from these systems. Alternatively, where total removal is not feasible, suppression techniques may reduce brook trout numbers enough to give native trout a fighting chance. In some cases, anglers are even enlisted to assist with these suppression efforts. Another tactic to combat brook trout invasions includes producing males with two Y chromosomes in hatcheries and stocking them into systems of concern. Known as a Trojan Y Chromosome strategy, YY fish are introduced to reproduce and eventually convert the entire population to all males, incapable of reproducing.

Despite negative impacts on systems outside their native range, brook trout popularity is so great that these fisheries continue to persist. Agencies now balance maintaining brook trout populations for recreation while also monitoring and managing these nonnative populations to ensure limited impacts on sensitive aquatic ecosystems and native trout.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.