Monday August 18, 2025

Rivers and their fisheries define cultures and traditions, and it is more important than ever to preserve them, ensuring these legacies are passed down through generations. From its headwaters in the Tibetan plateau to the Vietnam delta, the Mekong River is home to one of the most diverse and productive freshwater fisheries in the world, providing habitat to thousands of unique and charismatic aquatic species. In Southeast Asia, fish are a vital protein source and essential to the region’s culture and economy. Despite the river’s importance, many questions remain about how fish navigate its waters, especially against the backdrop of increasing hydropower development.

For decades, researchers have known, based largely on local ecological knowledge, that many fish species in the Mekong River make long-distance migrations, often spanning national borders. However, beyond the general challenges of tracking fish migrations in any environment, monitoring movements in a vast and dynamic river system like the Mekong, with unique hydrological and geomorphological features, is especially difficult. FISHBIO researchers had the opportunity to take part in this daunting task as part of the Wonders of the Mekong Project. The results, recently published in a scientific paper, provide insight into the migratory patterns of key fish species in this region. The fish migrations detected by this study were more complex and extensive than previously believed, suggesting that disruptions to key migratory routes could have even greater consequences than expected.

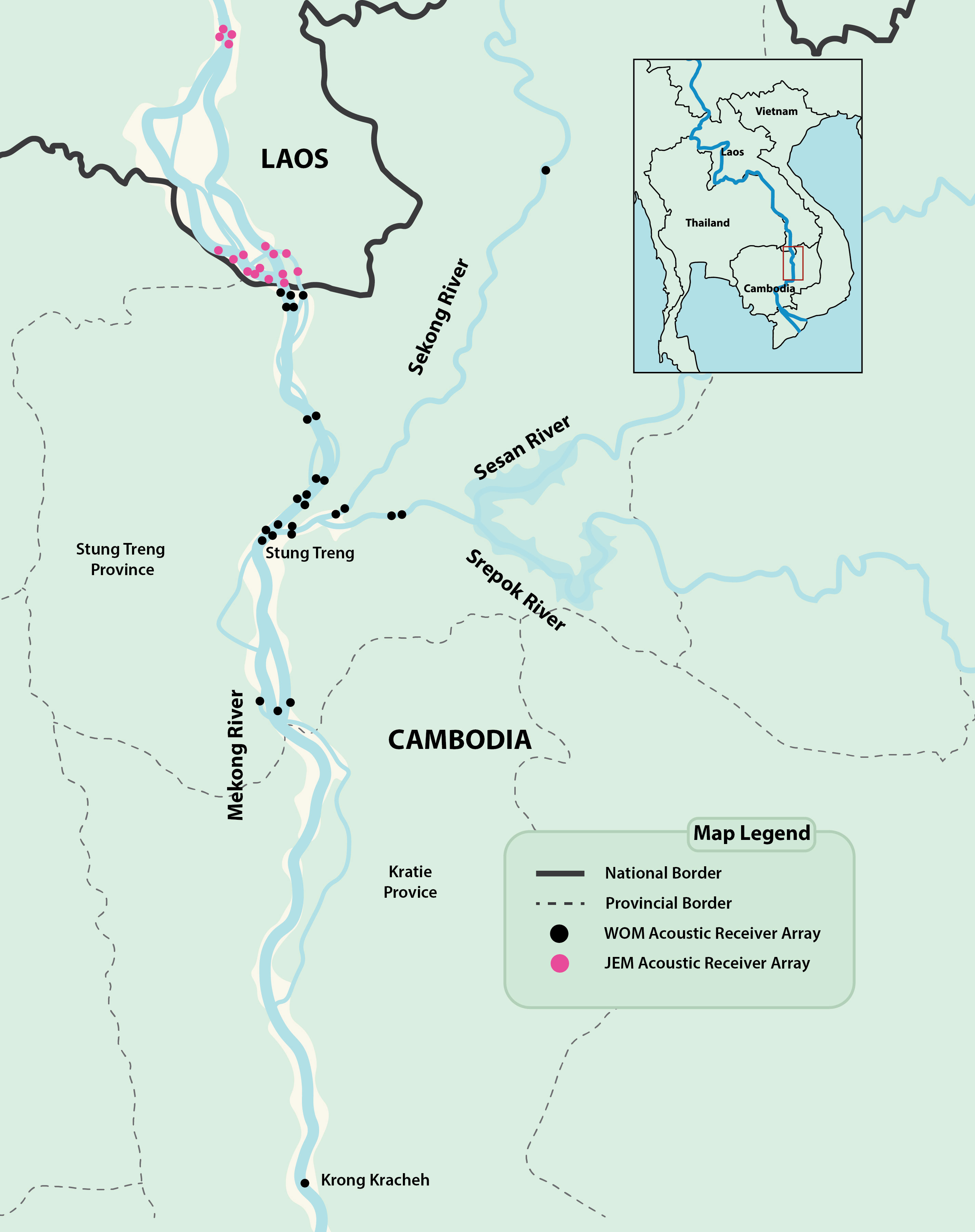

The collection of these empirical fish migration data required the installation of the first-ever large-scale international acoustic telemetry network in the Lower Mekong basin, comprised of more than 50 acoustic receivers covering over 300 miles. Between 2022 and 2024, a total of 300 individual fish from 23 different species were successfully tagged and tracked across key stretches of the Mekong and its tributaries (the Sekong, Srepok, and Sesan rivers, collectively known as the 3S Basin) in Cambodia and into Laos. Tagged fish included species thought to be both long- and short-distance migrants, as well as endangered species and fish of cultural and economic importance, like Julien’s golden carp (Probarbus jullieni) and several species of Pangasius catfish. Data analyses ultimately focused on 81 individual fish from 12 different species that were tracked for a long enough period of time (greater than 30 days) to make meaningful inferences about their migrations.

The study aimed to determine how fish respond to seasonal changes, whether they move across borders, and how their movements align with traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). Some movements confirmed long-held TEK, while others revealed previously undocumented behaviors. Researchers found that the upstream migrations of the snail eating pangasius (Pangasius conchophilus) align with what local fishers have long reported. These fish move upstream as the dry season transitions into the wet season, likely seeking spawning grounds, reinforcing the importance of maintaining connectivity along their migration routes.

Acoustic tracking of the black ear catfish (Pangasius larnaudii) revealed migrations between the Mekong and Sekong rivers, a pathway that had never been documented for this species before. In addition, the Asian redtail catfish (Hemibagrus wyckioides), a species previously thought to be a short-distance migrant, had sporadic, long-distance movements into the Sekong River, challenging previous assumptions about their movement ecology. Assuming that these unexpected long-distance movements are essential for their life cycle, barriers in their path could have unforeseen ecological consequences.

Notably, the study tagged and tracked what has now been recognized as the largest freshwater fish in the world, the giant freshwater stingray (Urogymnus polylepis). Over 18 months of monitoring revealed that the individual remained confined to a small home range containing several deep pools, highlighting the importance of protecting such habitats to ensure the survival of this iconic species.

Despite a ten-year temporary ban on dam construction along the main stem of the Mekong River in Cambodia, construction continues in Laos. This development includes ongoing work on 30 hydropower dams along the Sekong River in Laos and four dams on the Mekong in Laos, which are in various stages of planning, development, and construction.

While this study provides valuable new insights into Mekong movement ecology, it also raises more crucial questions. Most importantly, how can we ensure that these critical movement corridors remain intact? In the face of rapid developments, understanding where and when fish move can help policymakers and developers make more informed decisions to balance hydropower needs with ecological sustainability. The more we learn about the mysteries of Mekong fish migrations, the better equipped we are to protect one of the world’s most important freshwater ecosystems, preserve its rich fishing culture, and ensure the sustainable use of its resources.

Header Image Caption: Project team members deploying an acoustic receiver with the help of local fishing community.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.