Monday April 4, 2016

The question on the minds of many Californians is, “Has the forecasted Monster El Niño put an end to the drought?” In the months leading up to this past winter, news story after news story warned of the massive El Niño brewing and the floods that would ensue. While some storm events did result in swollen creeks, some dispersed mudslides, coastal erosion, and a washed-out road here and there, we didn’t see mass residential flooding anywhere near the scope experienced during 1982-83 and 1997-98 El Niño events. Since April 1st is a benchmark for measuring annual rain and snowfall, we thought it would be timely to take a look at just how much our recent wet winter affected the California drought.

The question on the minds of many Californians is, “Has the forecasted Monster El Niño put an end to the drought?” In the months leading up to this past winter, news story after news story warned of the massive El Niño brewing and the floods that would ensue. While some storm events did result in swollen creeks, some dispersed mudslides, coastal erosion, and a washed-out road here and there, we didn’t see mass residential flooding anywhere near the scope experienced during 1982-83 and 1997-98 El Niño events. Since April 1st is a benchmark for measuring annual rain and snowfall, we thought it would be timely to take a look at just how much our recent wet winter affected the California drought.

The Sierra Nevada snowpack is vital to California’s water supply. These snowcapped peaks are essentially the largest water reservoir in the state, supplying one third of California’s annual water needs in normal years. The average measurement of snowpack water content generally peaks on April 1st , and is used as an indicator of how much water runoff local watersheds will be receiving in following months. The Department of Water Resources conducted the latest snow survey on March 30th and results indicate 97 percent of normal for the Northern Sierra region, 88 percent of normal for the Central Sierra region, 72 percent of normal for the Southern Sierra region, and 87 percent of normal statewide. The snowpack this year is far from a drought buster, but it is a huge improvement over last year. The water content of the snowpack statewide in 2014-15 was only 5 percent of the historical April 1 average, the lowest amount ever recorded!

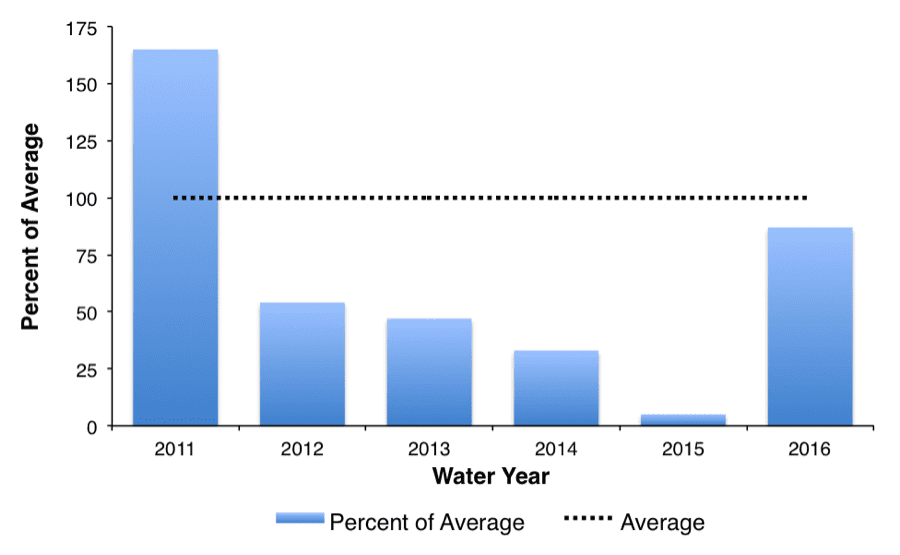

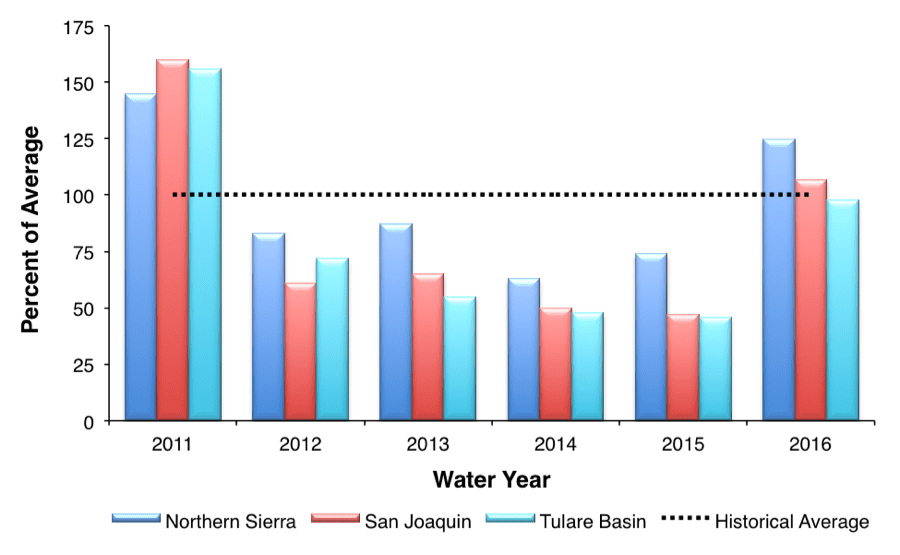

Fortunately for California, rainfall totals have been much better this year compared to the last four years. The Northern Sierra Precipitation Index is currently 125 percent of average, the San Joaquin Index is 107 percent, and the Tulare Basin Index is 98 percent. El Niño events typically bring extra rainfall to Southern California, as they did this year, but the impacts are less predictable for northern regions. Fortunately, after an unseasonably warm and uneventful February, March delivered a slow moving Atmospheric River that delivered 236 percent of average rainfall for the month in Northern California. As a result of the torrential downpours, many Northern California streams and rivers swelled to levels not seen since 2011. We recently visited Big Chico Creek to record a video of water overflowing its banks.

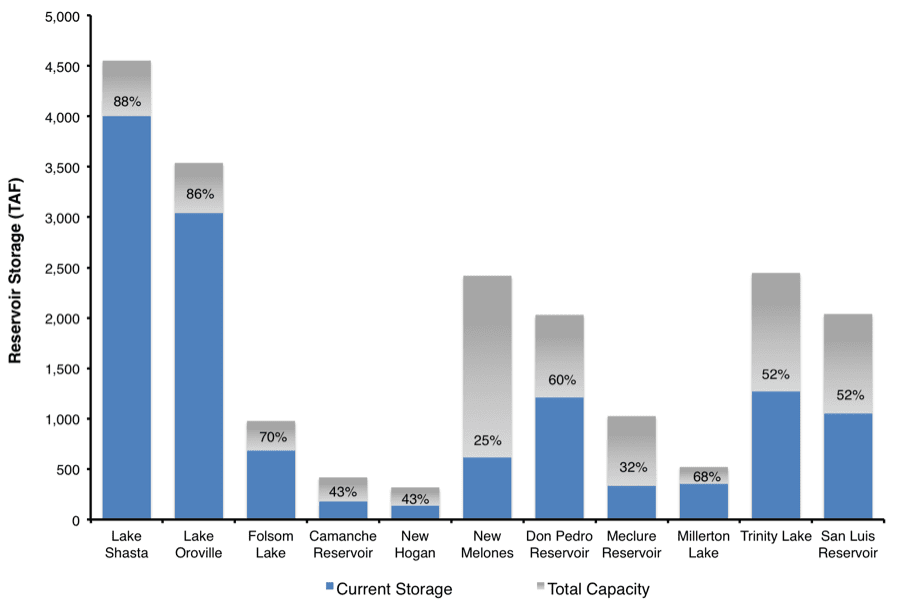

As a result of March precipitation, Northern California reservoirs like Shasta, Oroville, and Folsom have quickly risen to levels above average, and water is even being released water for flood control. Even though the reservoirs have not reached capacity, reservoir operators need to maintain space to hold runoff from rain events that may occur during the remainder of the wet season. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers uses models based on historic data to determine Top Conservation Pool levels for reservoirs in order to prevent downstream flooding. Even though water storage has improved in the north section of the state, Mother Nature is not necessarily fair, and many Central Sierra reservoirs still remain historically low.

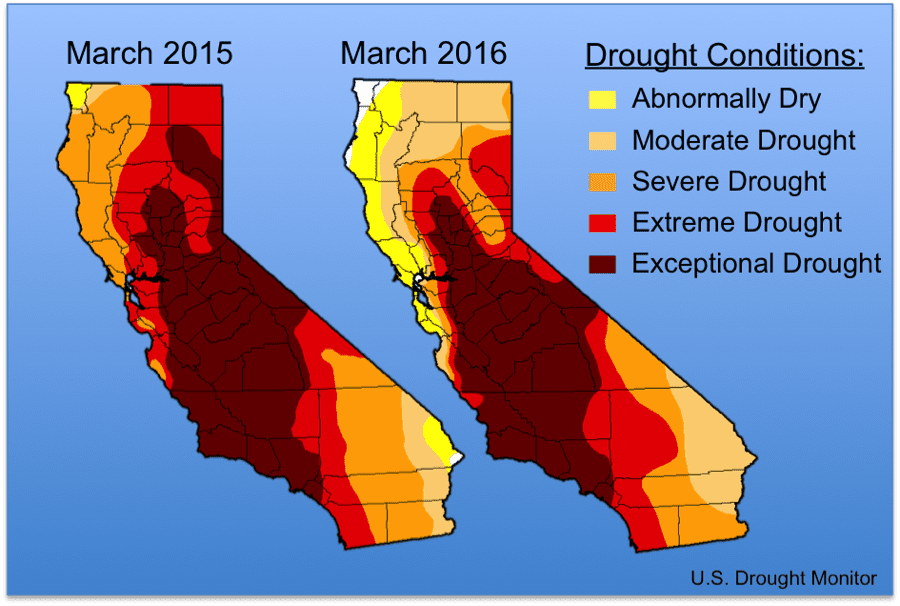

Unfortunately, a single year of near-average snowpack and slightly above-average rainfall is not nearly enough to bring California out of four years of extreme drought. As illustrated in the graphic above, drought conditions have lessened in Northern California along the north and central coast. However, the improved conditions have not been evenly distributed, and much of central and southern California remain in severe to exceptional drought status. Currently, 73 percent of the state remains in a “severe drought,” 55 percent in “extreme drought,” and 35 percent in the highest classification of “exceptional drought.”

Unfortunately, a single year of near-average snowpack and slightly above-average rainfall is not nearly enough to bring California out of four years of extreme drought. As illustrated in the graphic above, drought conditions have lessened in Northern California along the north and central coast. However, the improved conditions have not been evenly distributed, and much of central and southern California remain in severe to exceptional drought status. Currently, 73 percent of the state remains in a “severe drought,” 55 percent in “extreme drought,” and 35 percent in the highest classification of “exceptional drought.”

Although many in California are experiencing the impacts of the El Niño, also known as the ENSO (El Niño/Southern Oscillation), the effects are also being felt nation- and worldwide. As our colleagues in our Laos office can attest, the lower Mekong region is experiencing the “worst drought in 90 years,” which has been linked to the El Niño weather pattern. Due to low discharge of the Mekong River and its tributaries, saltwater is intruding into the Mekong Delta and devastating rice crops. Damage to ecosystems can also be caused by excessive rain, as was recently reported in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, where hundreds of thousands of fish have been killed due to massive amounts of storm runoff flooding waterways with fertilizers and other pollutants. El Niño damages are not limited to drought and floods: the effects can also be felt in marine ecosystems. Recent reports of coral bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef are due to increases in ocean temperature associated with El Niño. Fortunately for some and unfortunately for others, the El Niño is now diminishing and equatorial Pacific water temperatures are returning to neutral status. We shall see what next year brings.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.