Monday August 25, 2014

This third, continuous dry year in California highlights that droughts are not only stressful for people, they are also concerning for fish and wildlife – at least, for the native species. However, one group poised to benefit from the current tough times is the nonindigenous species that have been introduced to California’s waterways, which are often hardier and more tolerant of adverse conditions. Recent news stories reveal the drought is taking its toll on native fishes, particularly salmonids. Steelhead in the Napa River have reportedly experienced a sharp drop in the number of out-migrating juveniles because of warm temperatures and fish passage barriers. Salmon River spring-run Chinook are dying before spawning due to low flow and increasing temperatures. And salmon deaths have been reported in the Klamath Basin, a grim reminder of the 60,000 Chinook that died in the basin in 2002 when warming water temperatures perpetuated gill rot disease. Other wildlife are also at risk: this fall, when millions of waterfowl make their way down the Pacific Flyway, they will encounter dramatically reduced wetland habitat and food supply, conditions that breed competition and disease.

Salmonids and other freshwater fishes depend on the cold-water releases of Central Valley reservoirs, but hard times are coming if our current reservoir storage continues to decline. Shasta Reservoir, Lake Oroville and Don Pedro Reservoir are all below 50% capacity. California’s fourth largest reservoir, New Melones, sits at 25% capacity and is predicted to reach a mere 14% of capacity by the end of September. As a result, deep, cold-water pools in the reservoirs are diminishing, leaving only the warmer surface water to release for downstream fisheries. The future of salmon returning to spawn in future years may be in jeopardy if the drought continues. Some are proposing to collect salmon entering their natal rivers and strip them of their eggs and milt, then fertilize and incubate the eggs in a hatchery until river temperatures are low enough to return the eggs back to gravel beds to continue their life cycle. While this extreme intervention might only be considered because salmon are economically valuable, the effort wouldn’t help other native fishes present in the rivers year-round that must also contend with the warmer water.

These drought conditions may offer a window into the future, as the effects of climate change come to fruition. The California Environmental Protection Agency released a report last year chronicling evidence of climate change that can already be seen all around us: less spring run-off from diminished Sierra snowpack, rising reservoir water temperatures, and glacial melt. Researchers have been franticly churning out models to predict the effects of such changing hydrological patterns on our streams and rivers. A recent report by the National Wildlife Federation reveals that of 40 major U.S. rivers, half experienced significant warming over the past century, and 70 percent of rivers in the Southwest witnessed increased temperatures during the past 55 years.

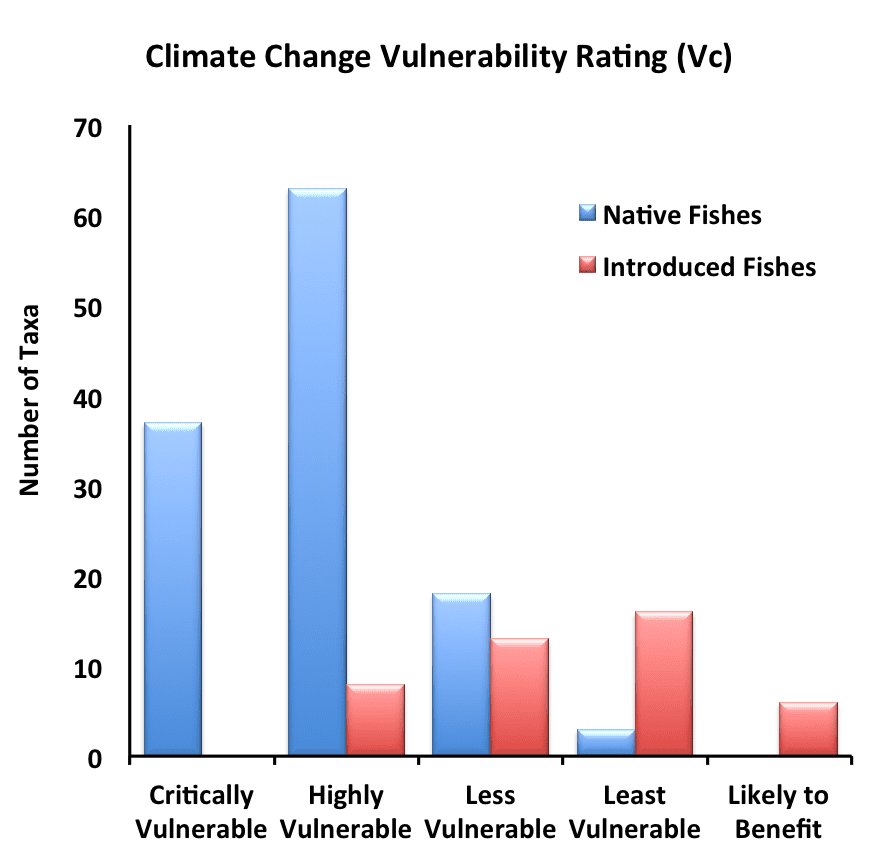

Diminished run-off and warming water temperatures do not bode well for native Western fishes that are adapted to cold-water habitats, but they do provide opportunities for non-native fish species to thrive, as many are well suited for warm-water environments. Many of the species introduced to California can tolerate a wide range of environmental conditions, and a multi-year drought and changing climate may allow these species to further impact and out-compete native species not adapted to the new temperature regime. A recent publication by U.C. Davis researchers indicates that the vast majority (82%) of native California fishes are highly vulnerable to climate change, whereas only 19% of introduced species are highly vulnerable (Figure 1, Moyle et al. 2013). The study predicts that most native fish populations will decline and some, mostly cold-water species, will go extinct – but most introduced fish will increase in abundance and range. It appears that it’s a good time to be a catfish, or other introduced fish, in California.

The relative vulnerability to climate change of native and introduced fishes in California. Data from Moyle et al. (2013).

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.