Monday June 12, 2023

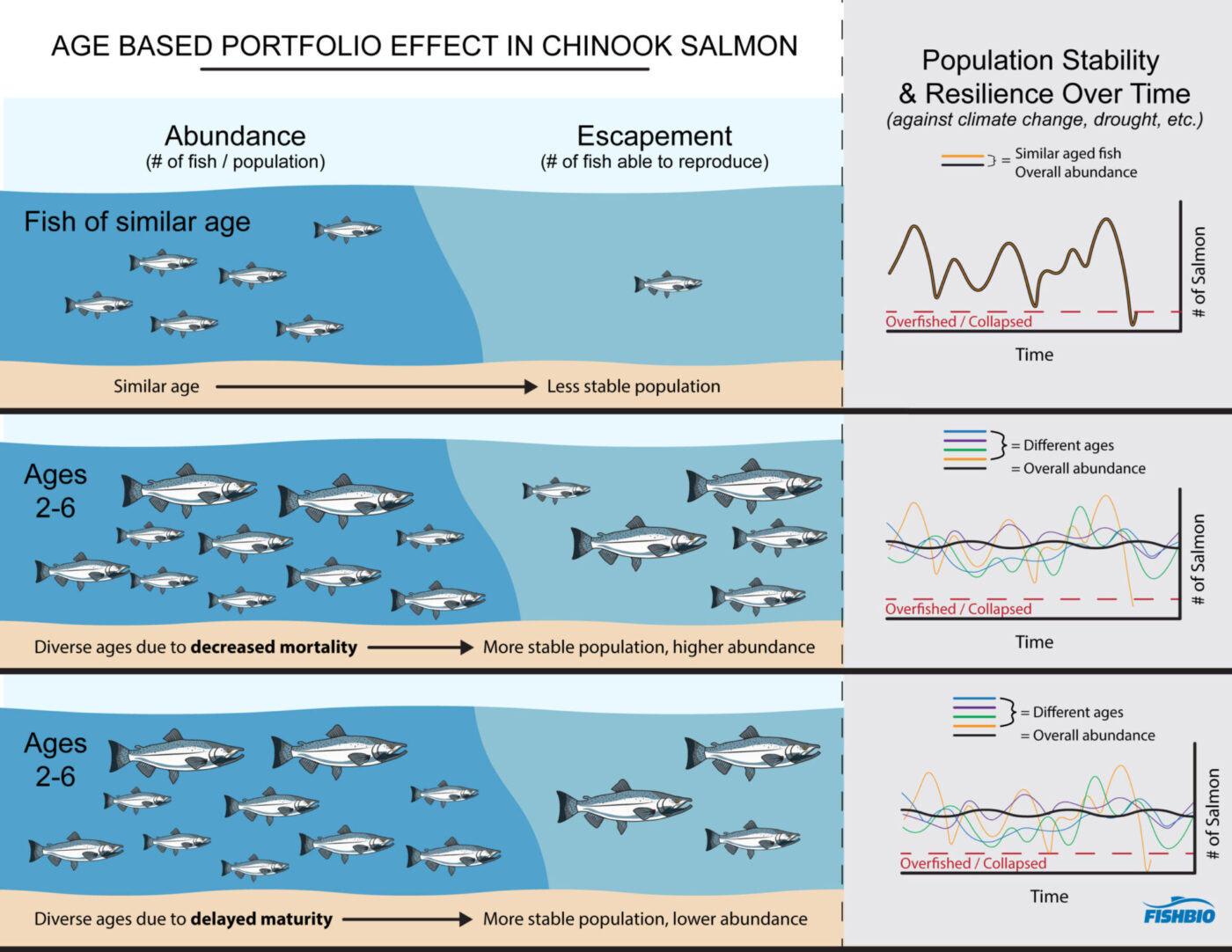

The portfolio effect is a concept from the financial industry but it can be applied across multiple disciplines, including ecology. It can be explained by the well-known proverb, “Don’t put all of your eggs in one basket”, and means that the overall risk can be reduced if an investment portfolio has a diverse set of stocks and bonds. The same principle applies to animal populations: diverse characteristics help to minimize risk by spreading the consequences of risk across the population and across a variety of ages, generations, or life histories. A study published in January of 2023 investigated how a diverse age class portfolio effect in Sacramento River fall-run Chinook (SRFC) salmon may benefit Pacific salmon populations, especially during prolonged drought, rising temperatures, and other irregular environmental conditions caused by global climate change. The researchers found that the negative impacts of climate change were reduced when multiple age classes were present in spawning populations. In Chinook salmon, age at maturation, or the age at which a fish is physically able to reproduce, is a heritable trait, but concerningly, it is becoming more common only to see one or two age groups within the salmon population return each year, as predicted by researchers over 40 years ago. In addition, the maturation age is getting younger in Pacific salmon populations. About a century ago, most Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in California’s Central Valley returned to spawn at age 4, and the spawning population in a given year included individuals between 2 to 6 years of age. However, today, most returning Chinook are 2 or 3 years old, and older individuals are rare. This change in age structure is attributable to several reasons, including exposure to fishing pressure, natural mortality, and hatchery practices. Intuitively, the more fishing seasons a salmon is exposed to while in the ocean, the higher the chance it will be caught (or die of natural causes, such as consumption by a predator), over time reducing the number of fish that survive to reproduce at older ages. Hatchery practices, often driven by predetermined production targets, don’t (and can’t) mimic male and female pairings that would occur naturally in a river.

For their study, the researchers modeled the effects of mortality and age at maturity on SRFC age structure in the face of severe drought conditions. Age distribution, also called age structure, in a population was heavily influenced by mortality (including natural and fishing mortality) and maturation. The results of the study indicated an increase in the number of fish annually returning to the river to spawn when the population had a diverse age structure that was primarily driven by low natural mortality. However, the results also revealed that, when a diverse age structure in a population is primarily driven by delayed maturity, the overall population decreases. The researchers also found that populations with a diverse set of ages remained fairly stable in size from year to year, regardless of the underlying drivers. The researchers concluded that a population with a diverse set of ages is more stable and robust and can buffer against the negative impacts of drought and other consequences related to global climate change.

While expected to be beneficial, achieving a more diverse age structure in salmon populations is difficult. Curbing natural mortality seems impractical and is likely not feasible, and scientists won’t be reducing the number of sea lions or killer whales – or increasing alternative prey for these animals – anytime soon. Because the SRFC population is dominated by hatchery-produced fish, the researchers suggest adjusting hatchery practices to aim for restoring age structure and life history diversity, focusing less on the total number of fish produced. Studies like this are especially important in light of the recent low forecasts for returning adult salmon numbers in California. The conservation of this iconic species and its ecological, cultural, and economic value in the face of worsening climate conditions requires resource users and managers to consider every tool at their disposal, including the restoration of age diversity within salmon populations.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.