Monday July 3, 2023

For millennia, humans have been dramatically altering the natural environment, particularly through the modification of waterways. The damming of rivers for water storage, flood control, power supply, and recreation has greatly modified the hydrology of many basins to fit human needs, and this is particularly true of California’s Central Valley. Although these massive waterworks have allowed for rapid development of cities and agriculture, they have at the same time considerably altered life for migratory fish by fragmenting available habitat and reducing access to cooler waters upstream. In fact, scientists have demonstrated that habitat fragmentation and limited migration corridors have directly contributed to declining fish populations around the world. With a growing understanding of these impacts, managers and scientists have made numerous attempts to address the challenges that dams pose to fish populations, including installing fish ladders, conducting downstream restoration, and trapping and trucking fish over dams. Fish ladders have been the standard approach for years to improve fish passage at dams and other man-made structures, however, they have had varying degrees of success. Fish ladders consist of concrete or metal structures with pools or pockets that fish can use to rest while they ascend and pass over an impediment and continue their journey upstream. While these ladders can be effective for strong swimmers capable of leaping out of the water, like Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytchsa) or steelhead (O. mykiss), this solution is less effective for smaller species, juveniles, or larger fish like sturgeon. Another drawback to the fish ladder approach is that these designs, while they can be effective for facilitating passage, do little to improve habitat in already degraded areas. A favored alternative to these designs is to create fish passages that emulate a more natural environment.

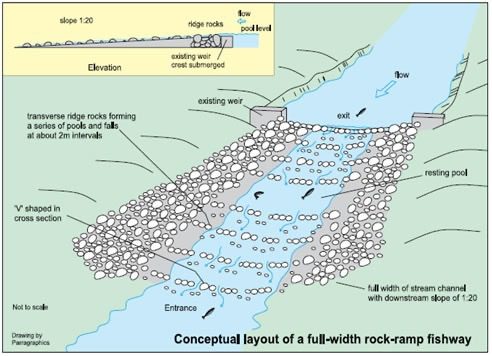

Known by several names, including nature-like, roughened channel, or rock-ramp fishways, these more natural structures have demonstrated passage accommodations for a variety of fish species with a wide range of swimming capabilities. As the name suggests, these fishways are designed to mimic natural river channels. Nature-like fishways generally feature a gradually sloping, open channel with a coarse streambed consisting of gravel and boulders to mimic a series of riffles and pools. This setup creates a more natural equivalent to the baffles and compartments featured in a traditional ladder. While a relatively novel technique here in the US, rock-ramp fishways have been utilized in Europe since the 1970’s as a form of streambed stabilization. In fact, the technique originated in Europe, and has only recently sparked interest in the states due to its relatively low-cost and restorative capabilities. Rock-ramp fishways are also an excellent example of ecological engineering, a growing field that aims to benefit nature and humans alike by using creative engineering techniques that mirror natural systems.

Ecological engineering practices work to blend human design with the natural environment, often utilizing natural resources or mimicking those resources within the build. In 1989, Mitsch and Jorgenson proposed the four fundamental principles ecological engineers should follow when designing their river and streambed restoration projects. Nature-like fishways should be built to be: 1) a part of and reflect nature, 2) self-designed and self-regulating, 3) sustainable (implying the longevity of an ecologically engineered system), and 4) ecosystem-based (conserving and mimicking the natural ecosystem by design).

Luther Aaland, a Minnesota river ecologist focused on dam removals and river restoration, notes several advantages afforded to nature-like fishways when compared to more engineered solutions. Notably, fish are drawn to cues from changes in current, and a more natural streambed would likely lead to less disorientation than one with a more uniform channel. Further, when compared to a standard ladder, the more natural streambed provides suitable spawning habitat, while also generating more area for fish to potentially rear during their journey. In general, fish tend to prefer rough, natural substrates for spawning and rearing, a type of habitat that smooth concrete just cannot provide. The diversity in the composition of the riverbed provided by roughened channels creates minor pockets where small fish can rest and invertebrates can thrive, mimicking a natural stream ecosystem.

Fish passage and habitat connectivity are integral for the conservation of imperiled freshwater fish species, and fishways and fish passages that facilitate migration are critical components in sustainable water resource management. Conventional fishways are tried and true and have undergone extensive research for the particular species they are designed for. However, nature-like fishways should not be overlooked due to their multiple benefits including their multi-species passage ability and harmonious integration with their natural environment. With their low cost and potential for habitat restoration, nature-like fishways can be another tool to help promote the recovery of special-status species and their habitat while maintaining the human utility of the developed infrastructure.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.