Monday April 28, 2025

Earlier this month, news of the 2025 commercial salmon fishery closure off the coast of California was announced for an unprecedented third consecutive year. Although the outcomes of last year’s salmon season – or lack thereof – seem bleak, FISHBIO has taken the opportunity to crunch the numbers and examine key findings from previous years’ salmon abundance projections, estimated escapement, and harvest values to help understand how salmon populations are faring across the Central Valley in response to fishery management decisions. The 2024 salmon population, sadly, continued the downward trend that was exhibited in previous years. Although the fishery has remained closed for three consecutive wet water years, the overall spawner abundance (termed “escapement”) has not shown signs of recovery and continues to fall short of statewide management goals. While there are some positive developments from the 2024 population, threats facing salmon in California continue to be multifaceted.

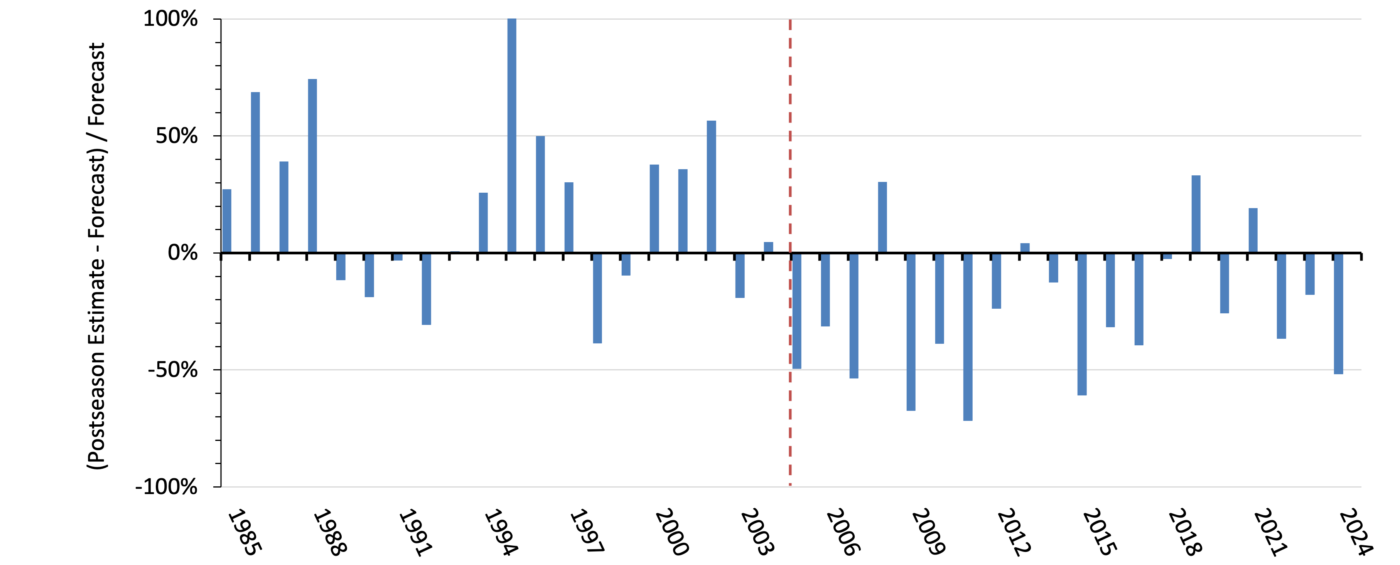

Each spring, the Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) publishes a report on the previous year’s salmon fisheries along the West Coast, which details harvest totals and socioeconomic benefits from the California ocean fishery. It also includes escapement totals and provides an opportunity to compare these numbers with the preseason predictions that were used to set harvest regulations for that year. Inaccurate preseason predictions can have severe consequences – an underestimation can impose unnecessary restrictions on the commercial fishery, and an overestimation can lead to reduced escapement and low numbers of fish available for in-river recreational fishing. Since 2005, Central Valley salmon abundance has been overestimated in 80% of all years (Figure 1), continuing to hamper effective management of the fishery. In 2024, the population was overestimated once again, with estimated escapement about half of the forecasted abundance.

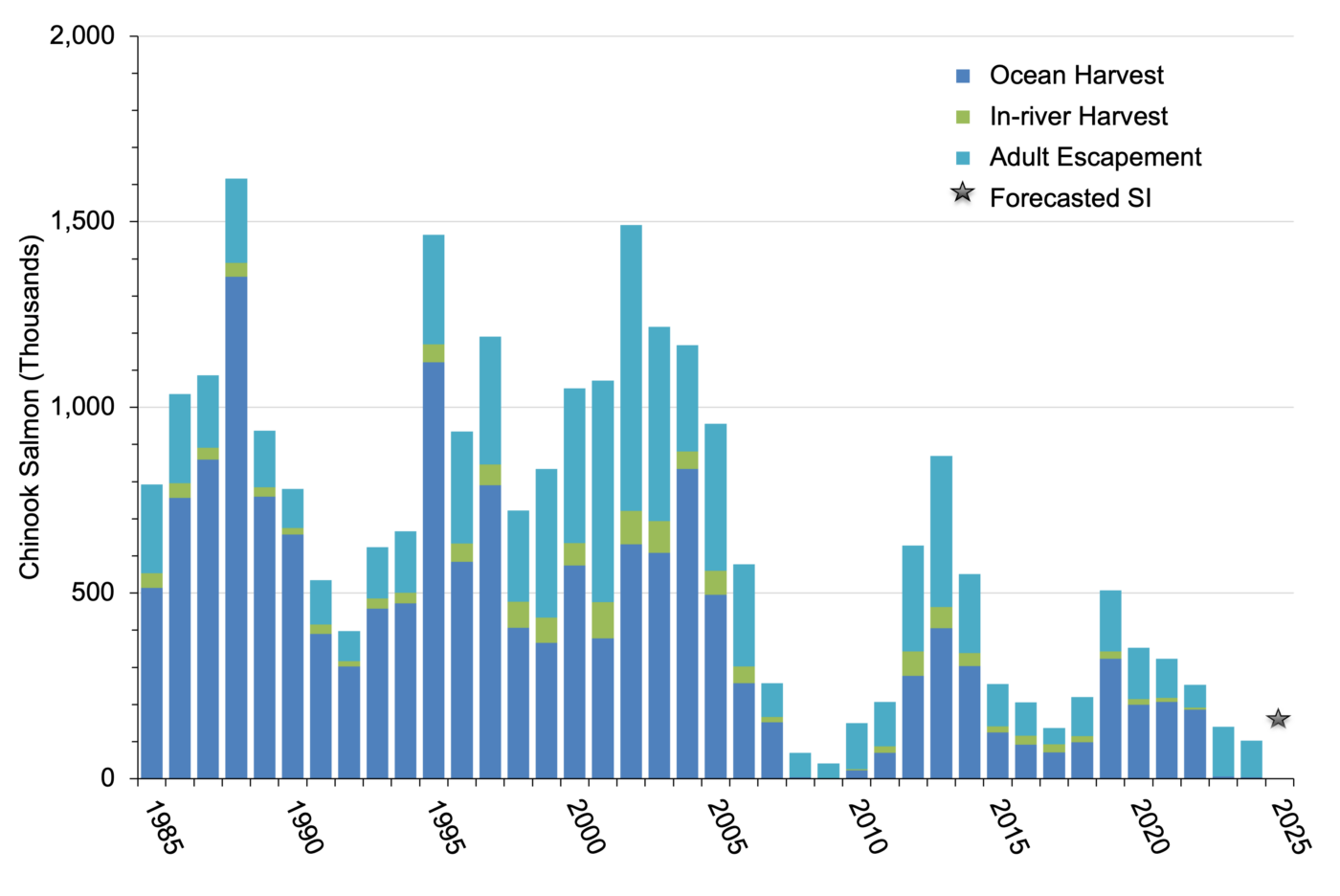

In California, the PFMC report highlights fall-run Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in the Sacramento River Basin, as this population contributes most of the fish caught in the ocean fishery. The metric used to represent the abundance of this population is the Sacramento Index (SI), which is the total number of adult fish (ages 3-5) available in the ocean that may be either harvested or escape to spawn in natural areas or hatcheries in the Central Valley. The preseason forecast for 2024 predicted an SI of 213,622 fish, including a spawner escapement of 180,061 hatchery and natural area spawners. This predicted SI was higher than the previous year’s prediction and would have resulted in a spawning escapement at the upper end of the management goal, but, unfortunately, the actual returns were far less than predicted. The actual SI in 2024 was 102,965 fish, 35% lower than the prior year and 58% lower than the previous five-year average of 314,169 fish. Given the second consecutive shutdown of the salmon fishery in California in 2024, the exploitation rate (or percentage of fish that were commercially harvested) was again extremely low – at 3.6% – due to minimal harvest of Sacramento River Basin fish in other states. As such, the majority of the salmon population returned to Central Valley rivers and hatcheries to spawn.

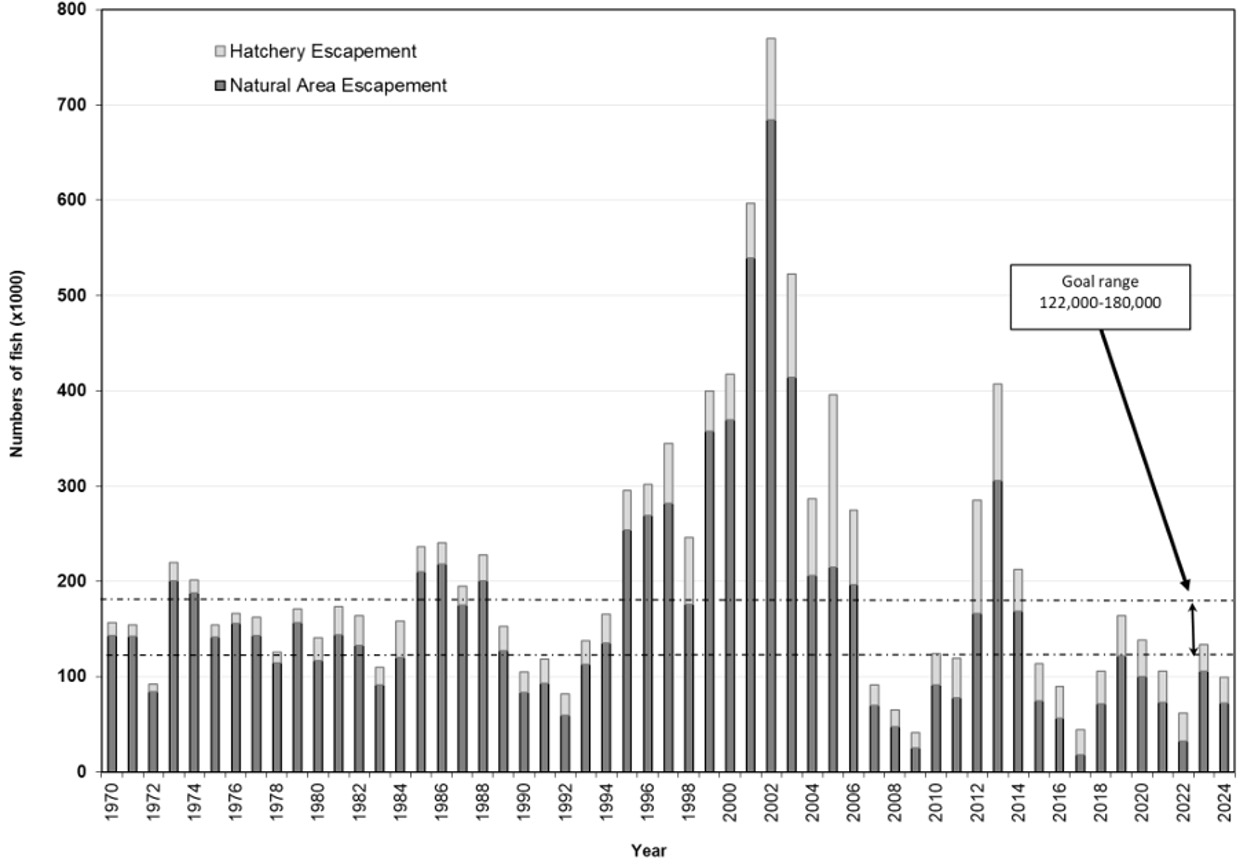

An estimated 99,274 fall-run Chinook salmon “escaped” the harvest and spawned in hatcheries and natural areas of the Sacramento Basin in 2024, which is well below the long-term management goal of 122,000 hatchery and natural area spawners. Escapement in 2024 was 26% lower than the previous year (133,638 fish) and 18% lower than the average from the previous five-years (120,617; Figure 2). The number of natural-area spawners (72,440) exceeded the number of hatchery returns (26,834), which is common in most years but is sometimes reversed in low-escapement years, as seen in 2017 (Figure 3). Notably, hatchery-origin fish likely comprise a large percentage of the natural area spawners.

The salmon returning in 2024 to the Sacramento River Basin were likely influenced by relatively poor outmigration conditions in early 2022, when the majority of the returning fish originally outmigrated to the ocean as juveniles. This outmigration occurred during a third consecutive year of extreme drought in California, conditions which are known to result in poor survival due to the impacts of low flows and high temperatures. Even so, while survival in the San Joaquin River (SJR) Basin is generally much lower than in the Sacramento River Basin, returns to the SJR Basin have increased tremendously over the last three years: 2023 saw an increase of 263% over the prior year, and 2024 estimates were even higher than that with a total estimated escapement of 32,246 salmon, or 24% of the Central Valley total. The majority of these fish returned to the Mokelumne River, which received roughly 74% of all natural area spawners in the basin, followed by the Stanislaus (11%), Tuolumne (7%), Calaveras and Cosumnes rivers (combined total of 7%), and the Merced (2%). The SJR Basin has historically constituted less than 10% of the total Central Valley escapement, but since 2015, its average contribution has increased to 15.9%.

The increased relative proportion of escapement to the SJR Basin over the past few years may be partially attributed to increased trucking and release of hatchery smolts at off-site locations (meaning outside of their natal waters), which increases juvenile survival but increases straying of returning adults. The Mokelumne River Hatchery, for example, has consistently trucked most of their fish production directly to the San Francisco Bay, boosting the number of returning adults to the Mokelumne River and other nearby streams and making headlines in the last couple years with high counts of returning salmon.

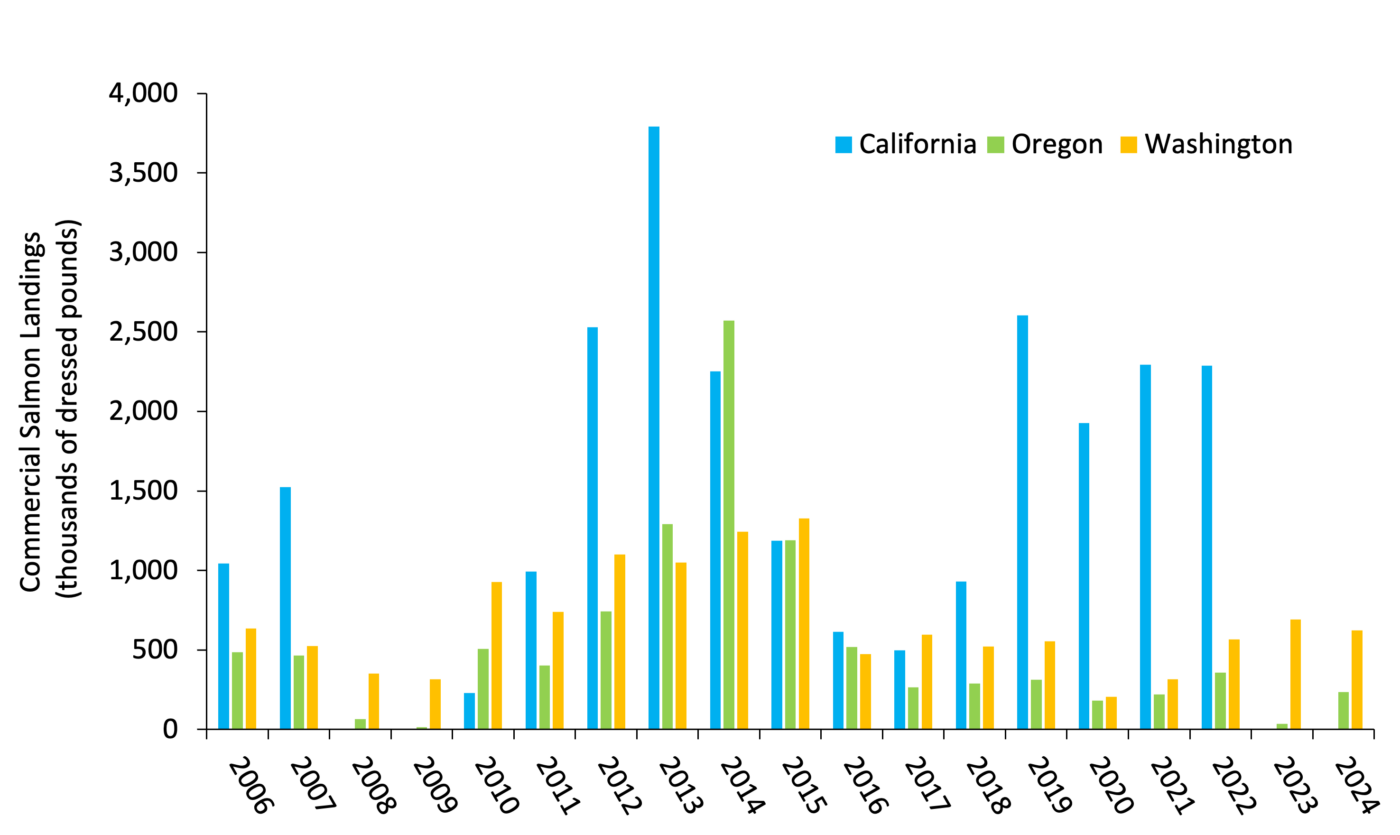

Prior to the fishery closures beginning in 2022, most (roughly 85%) Pacific Coast commercial Chinook (by weight) were landed in the Fort Bragg, San Francisco, and Monterey ports of California (Figure 4). With California commercial fishing halted for two years, however, West Coast Chinook landings have shifted north to port areas in Washington, where almost half of coastwide Chinook landings were caught in 2024. Data from the last year with a harvest in California (2022) suggest the fishery closure resulted in a loss of over $17 million in ex-vessel revenue, or value of fish sold at the dock by commercial fishers. In comparison, the 1979-1990 inflation-adjusted average of landings revenue from the California commercial salmon fishery – which at the time included coho salmon (O. kisutch) landings – was $40.5 million.

Anglers and commercial fishers have, again, received discouraging news from PFMC this year, with reduced forecasts leading to the longest, multi-year fishery closure in California’s history, exceeding that of the previous closure occurring from 2008 to 2009. If preseason forecasts are correct, there will be an estimated 165,655 Sacramento River fall-run Chinook salmon in the ocean this year. This forecast is 22% lower than 2024’s projection and 46% lower than the previous five-year average of 304,820. Fisheries scientists, commercial fishers, and recreational anglers were hopeful to see improved salmon populations and the return of a salmon fishery in 2025. However, after a third year of disappointing numbers, harvest managers made the difficult decision to keep the commercial fishery closed and only allow limited recreational fishing. The low forecasted abundance this year was surprising given that the majority of fish returning this year would have migrated to the ocean as juveniles during one of the wettest years on record in 2023, when survival was expected to be relatively high.

Like a double-edged sword, this historical salmon fishery closure continues to impact California’s commercial and recreational fisheries economies, but it is necessary to protect salmon populations after the dramatic collapses experienced in the last decades. While a salmon fishery closure of this duration has never before occurred, and undoubtedly compounds the hardship experienced by the broader commercial and recreational fishing industry statewide, the fisheries community – including scientists, managers, and anglers – holds hope that the closure will have a positive effect on future stock numbers. After three consecutive years of stream conditions associated with high juvenile survival, and decreased pressure from commercial and recreational fishing, there are reasons to be optimistic about future salmon seasons.

This post was featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.