Monday March 29, 2021

One year into the pandemic, COVID-19 continues to affect every facet of life – including the world of science. Loss of research, time, and information resulting from pandemic shutdowns is taking a toll on fisheries and marine science organizations. In a perspective published in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, fisheries science leaders from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) across the United States discuss how their organization is addressing COVID-19 challenges and offer possible solutions to help other fisheries organizations navigate the pandemic (Link et al. 2020). These include possible methods for addressing uncertainty and limiting further data loss, and the benefit of collaboration to mitigate the effects of the coronavirus on fisheries and marine science research.

When faced with adversity, a helpful instinct might be to look to history for answers and advice. Although fisheries management was not as established during the 1918 influenza pandemic as it is today, a key lesson from that event is to keep human health and safety a priority while considering adjusted methods for fisheries operations. Other past disasters that have impacted fisheries have been more localized and short lasting, such as hurricanes and oil spills. These emergencies have often brought academia, industry, and government agencies together to respond quickly. Collaboration, preparedness, and knowledge of the present issue are all important elements of a safe and successful response. COVID-19 now presents another learning opportunity to add to the tool box of guidance for future disasters.

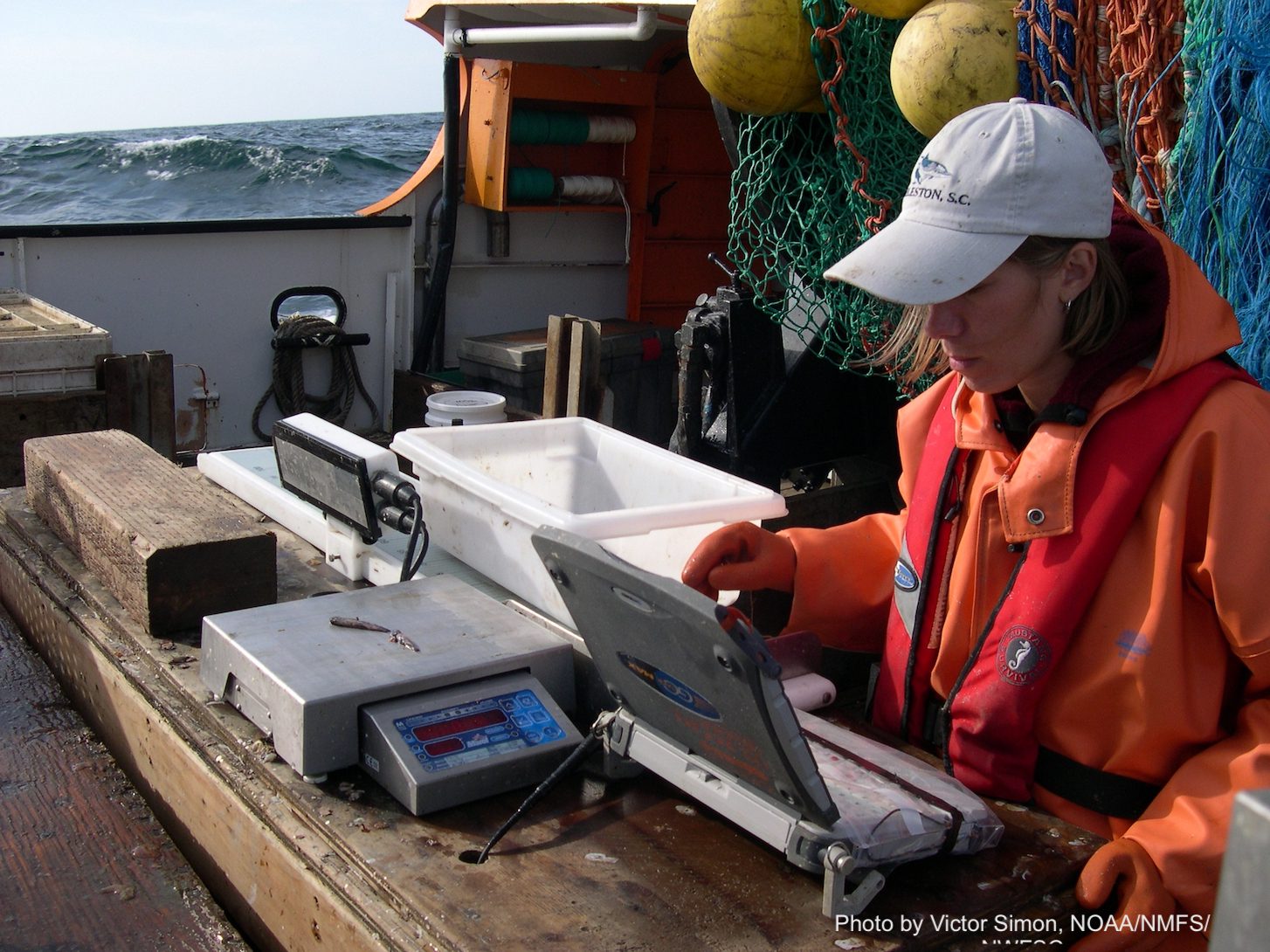

Data collection is one of NOAA Fisheries’ many activities that has been disrupted by the pandemic. NOAA collects substantial amounts of data throughout the year that are critical for monitoring changes in climate, fish populations, and ecosystem health, as well as forecasting natural disasters. However, in 2020, the fisheries agency needed to cancel over 50 surveys, resulting in a loss of over 1,500 days at sea. Data loss makes estimates and models, such as stock assessments, less precise and increases management uncertainty. However, the authors discuss a few options for dealing with lost data. They advise that some stock assessments can be projected forward for an additional year based on past data, and some models can be updated with less frequent new data when they are available. They note that data gaps of single or multiple years will have a greater impact on shorter lived species, such as salmon or shrimp, and obtaining data on catch per unit effort from the fishing industry could be particularly important for assessing stocks of these species. When it comes to setting catch limits, the authors suggest keeping regulations similar to the preceding years, as well as adopting a precautionary approach that adds buffers to catch limits to address the uncertainties of missing data. They do note that such a precautionary approach focuses on benefiting fish populations, and not the fishing communities that rely on aquatic resources. These communities may therefore require additional economic support as a result.

In spite of the pandemic, increased collaboration is possible within fisheries and marine science organizations, and also with the public. NOAA vessels typically operate independently of fisheries when collecting data on living marine resources. However, in light of restrictions on research efforts, data collection could be expanded to include input from the fishing industry and other citizens. For example, fisheries sampling could be carried out by port agents to double check fish landing reports from dealers, processors, and fisheries association leaders. Citizen science approaches could engage people eager to help the scientific process in a time of need, such as relying on anglers to report the amount and types of fish caught during recreational fishing trips. Taking a critical look at the many challenges and opportunities for fisheries research and management as a result of COVID-19 can help scientists better prepare for facing future disruptions.

This story was written by Andrea Dempsey as part of an internship with FISHBIO.

This post featured in our weekly e-newsletter, the Fish Report. You can subscribe to the Fish Report here.